Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

We humans have sent a wide array of animals into space.

Starting with fruit flies on February 20, 1947 (the fruit flies survived), we continued with monkeys, tortoises, guinea pigs, frogs, fish, rabbits, spiders, jellyfish, newts, scorpions, gerbils, geckos, rats, parasitic wasps, beetles, roundworms, brine shrimp, crickets, snails, sea urchin, silkworms, bees, tardigrades, ants, and yes… cockroaches.

But the first dogs to orbit the earth and return alive from space are my personal favorites: Belka and Strelka, Soviet space superstars.

Here’s a Soviet disco jam to set the vibe for your reading experience.

On August 19, 1960, as part of the Sputnik 5 mission, Belka and Strelka launched into orbit accompanied by rats, mice, a rabbit, flies, and several plants and fungi.

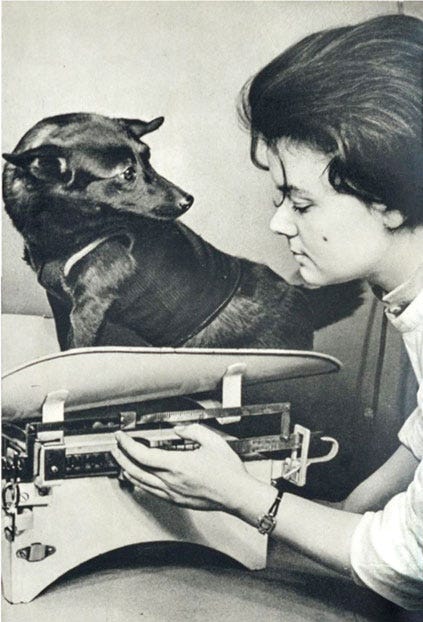

The two dogs were hand-selected for the mission by members of a special Soviet department formed to find dogs that fit specific criteria: female, aged 2-6 years, weight under 6 kilograms and height below 35 centimeters. Belka and Strelka were strays, which the scientists preferred because they believed street dogs could endure the harshness of space better than coddled purebreds. Only female dogs were selected because they allowed the engineers to build a much simpler waste-disposal system in the space capsule. The scientists also looked for light-shaded coats because those dogs would be easier to see in press photos.

Lyudmila Radkevich, a researcher for the space program, remembers how a soldier drove her around Moscow’s suburbs looking for stray dogs, chasing them by foot and attempting to measure them with her ruler. Around 60 dogs were picked at the start of the program, and they were regularly seen wandering the Institute for Medical and Biological Studies.1 Scientists decided that the dogs would be sent in pairs, since the animals felt better and calmer when accompanied. The dogs went through medical, physical, and behavior tests and only about a dozen were actually trained for orbital flights, including Belka and Strelka.

Like all serious astronauts, the two dogs were put through robust training before their mission. They endured centrifuge tests simulating the G forces of launch and reentry, were subjected to loud noise, high light, and vibration to prepare them for being in a spacecraft, and taught to sit still for long periods of time. The Soviets also developed a diet specifically for the dogs so they would be less affected by the pressure in space. And, of course, a special suit was created for Belka and Strelka. The suits regulated the dogs’ body temperature and oxygen supply and took readings for the team back home.

The dogs didn’t know this of course, but their mission was terrifyingly risky. The first dog that the Soviets sent into orbit, Laika (Лайка or "Barker"), didn’t come back. The return technology hadn’t been developed yet, so she served as an unwitting sacrifice to science. (She became a national hero, at least.)

Then the Soviets attempted to send another pair into orbit, Chayka ("Seagull") and Lisichka ("Little Fox"), who died when a booster exploded just after their launch. Lisichka was the favorite of Sergei Korolev, the genius behind the Soviet space program. Colleagues saw him hug her and whisper “I really want you to come back,” before takeoff.2 After the failed launch, the Soviets decided that all future dogs were to be supplied with an ejecting capsule, so they could catapult to safety if something went wrong.

That was the only change made before the next launch, just 18 days later. The next dogs chosen to orbit were regarded as the most intelligent, quick-witted, and hardy of the dozen. These dogs went by Vilna and Kaplya, but just before launch, one of the scientists who worked with the dogs decided that they should have western-sounding names to appeal to a wider audience. The team changed their names to Belka (Белка, literally "squirrel" and also "whitey") and Strelka (Стрелка, "little arrow"). Belka was appointed as leader of the mission because she was more active and successful in tests.

When Belka and Strelka were sent into space in August of 1960, they were on film. You can watch footage below of their launch, trip, and return. (Seriously, watch this video!)

During takeoff, Belka and Strelka tensed and their heart and breathing rates increased. Then, as Sputnik 5 settled into orbit they stopped moving.3 During the fourth orbit, Belka vomited, which supposedly woke both of the dogs up from their stupor. “From the video recorded on board, you can see the dogs moving around and barking, medical data showed they were calm and not overly stressed.”4 They were served an in-flight meal of Russian meat and kholodets from an elaborate, automated trap door, which you can see demonstrated in the video above.

After 17 laps around the earth and more than 24 hours in orbit, ground controllers fired the retro rockets and the dogs descended back to Earth. When the capsule was opened, Belka and Strelka appeared happy to be back home.

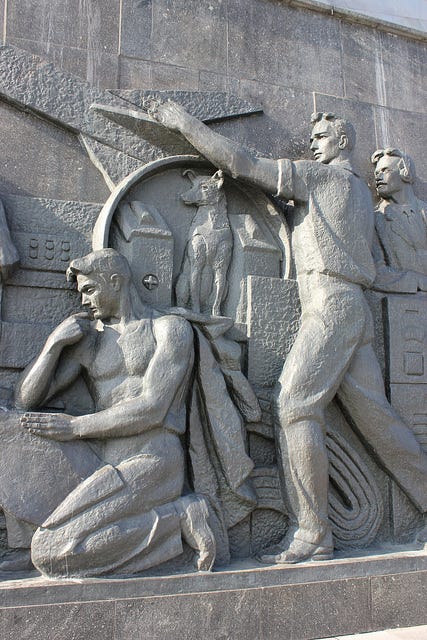

Within hours they were on the celebrity circuit. The dogs appeared on the covers of newspapers and were honored on TV shows, posters, stamps, marquees, calendars, and more. “It was a sensation on a worldwide scale, the second breakthrough of this level after the launch of the satellite.”5

After a few more flights with dogs, the Soviet Union put the world's first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961. Gagarin reportedly joked: “Am I the first human in space, or the last dog?”6

Eventually Belka and Strelka were allowed to retire from the Soviet space program and public life.

Belka lived out her retirement in a Moscow zoo, where she was treated like royalty, offered a special enclosure, and visited daily by members of the space program.

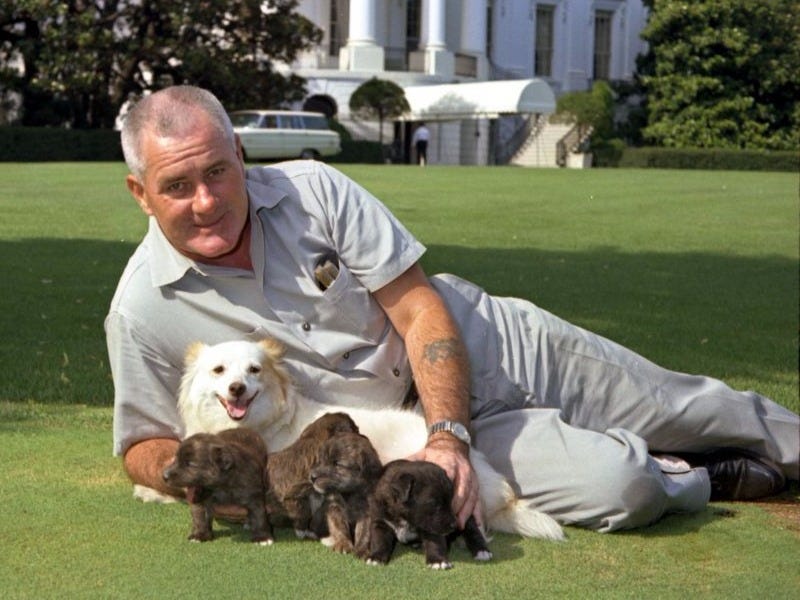

Strelka was sent to a high ranking officer in the Soviet government, where she became part of their family and had six puppies with a male space dog named Pushok who had participated in many experiments but never made it into space. You can see the puppies here:

The space race was part of a geopolitical chess game between the United States and the Soviet Union. Without the animosity and fear stewing between the two nations during the Cold War, perhaps Belka and Strelka would have never left the streets of Moscow.

Which is why the next chapter in this space dog story is so unexpected. I suppose it’s a testimony to the immense power dogs have to spark otherwise impossible bonds between people.

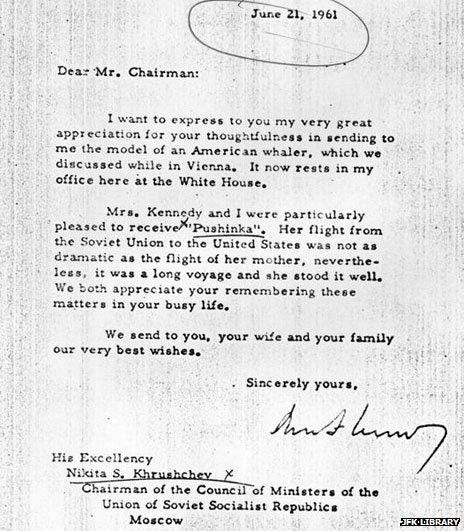

In June 1961, two months after Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth, President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev held their first joint summit in Vienna. The meeting was, by all accounts, very difficult.

During dinner, Khrushchev sat next to Jacqueline Kennedy. Caroline Kennedy later recalled to the BBC that her mom "ran out of things to talk about, so she asked about the dog, Strelka, that the Russians had shot into space. During the conversation, my mother asked about Strelka's puppies. A few months later, a puppy arrived and my father had no idea where the dog came from and couldn't believe my mother had done that." Khrushchev had sent one of Strelka’s puppies—a member of the Soviet space dog royal family—to live at the White House. Her name was Pushinka (Пушинка or "Fluffy").

When she arrived, Pushinka was examined by the Central Intelligence Agency at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center over fears that she may be concealing an implanted listening device. She was x-rayed, screened with a magnetometer, and inspected with a sonogram. Pushinka was found free of any subversive devices and welcomed into the family of White House pets.7 In fact, Pushinka and Caroline Kennedy’s Welsh terrier Charlie had four Russo-American puppies together, which President Kennedy referred to as the “pupniks.” “I like to think of it as a Cold War romance,” says Andrew Hager, historian in residence at the Presidential Pet Museum.8

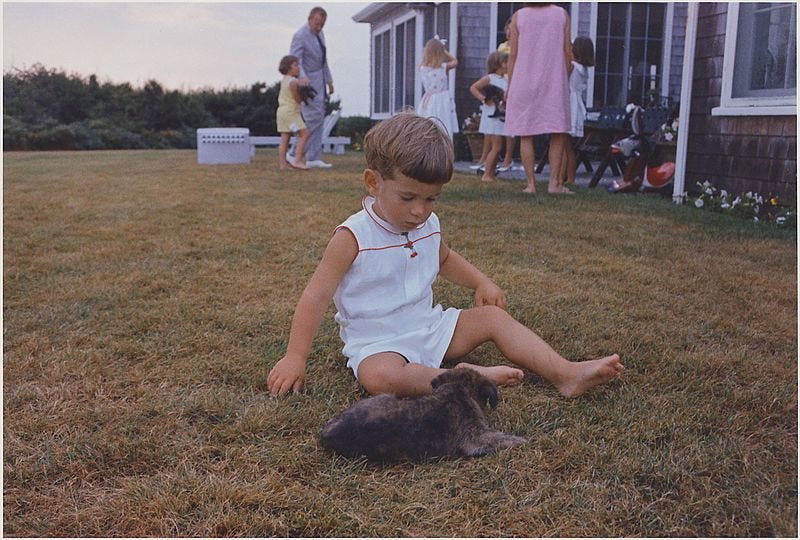

The White House received 5,000 written requests from members of the public asking if they could have one of Pushinka and Charlie's puppies. Two of the puppies, Butterfly and Streaker, were given away to children in the Midwest. The other two puppies, White Tips and Blackie, stayed at the Kennedy home on Squaw Island but were eventually given away to family friends.

In October 1962, just 16 months after the Vienna summit and the delivery of Pushinka, Kennedy and Khrushchev found their nations on the brink of nuclear war. The United States had photographs proving that the Soviets had stationed nuclear missiles in Cuba that were capable of striking American cities.

Eventually, Khrushchev agreed to dismantle and remove the missiles. Kennedy promised the United States would not invade Cuba and would lift the naval blockade on the island. "After the Cuban missile crisis the two men both said they were very different," Sergei Khrushchev, Nikita’s son, told the BBC.9 "We defended our treasures but we have one thing in common—we want to preserve peace and work for this together."

Historian Martin Sandler, a specialist in Kennedy's letters, believes that the communication between the two leaders that started in Vienna and continued afterwards through letters and gifts like Pushinka had a huge impact."In the end," he says, "that's what saved the world from nuclear destruction."10

The space dogs are part of why we’re all still here on earth.

When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Pushinka was given to a White House gardener and later gave birth to another litter of puppies. Andrew Hager, historian in residence at the Presidential Pet Museum, has attempted to track down Pushinka’s descendants but, so far, has not been able to find them. “Certainly, it’s still possible there are descendants of these Russian space dogs out there in the United States,” he said.11

Meanwhile, millions of people still go to visit Belka and Strelka every year at the Cosmonautics Memorial Museum in northern Moscow, where they are preserved as heroes for perpetuity.

One day, maybe we can go to the museum, too. Though these days it might be easier and safer for an American like me to go into orbit than into Russia. Somehow, we’re back where we started.

Space Dog Name Index

All of the space dogs had several nicknames at any given time in order to confuse the intelligence of other countries.12 And let me tell you, these names slapped! The scientists truly brought their creative A-game. Here’s a quick round up of the ones I could find, mostly from this blog.

Krasavka: "Little Beauty." Krasavka was also known as Kometka ("Little Comet") or Zhulka ("Cheater")

Chayka ("Seagull") was also known as Bars ("Snow leopard")

Laika was also known as Kudryavka (Кудрявка or “Little Curly:), Zhuchka (“Little Bug"), and Limonchik ("Lemon")

Pchyolka: "Little Bee"

Mushka: "Little Fly"

Chernushka: "Blackie"

Zvezdochka: "Starlet," named by Yuri Gagarin

Dymka: "Smoky"

Modnitsa: "Fashionable"

Kozyavka: "Little Gnat"

Lisichka: "Little Fox"

Damka: "Queen of checkers." Damka was also known as Shutka ("Joke") or Zhemchuzhnaya ("Pearly")

Tsygan: "Gypsy"

Lisa: "Fox" or "Vixen"

Ryzhik: "Ginger" (red-haired)

Smelaya: "Brave" or "Courageous"

Malyshka: "Babe"

Otvazhnaya: "Brave One"

Snezhinka: "Snowflake"

Veterok: "Light Breeze"

Ugolyok: "Coal" (Sorry buddy!)

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.amusingplanet.com/2021/12/belka-and-strelka-soviet-space-dogs.html

https://blogs.iu.edu/russianstudiesworkshop1/2018/11/07/a-reflection-of-hybrid-vigor-the-agency-of-dogs-in-space/

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20171027-the-stray-dogs-that-paved-the-way-to-the-stars

https://www.google.com/search?q=%E2%80%9CFrom+the+video+recorded+on+board%2C+you+can+see+the+dogs+moving+around+and+barking%2C+medical+data+showed+they+were+calm+and+not+overly+stressed.%E2%80%9D&rlz=1C5GCEM_enUS1010US1010&oq=%E2%80%9CFrom+the+video+recorded+on+board%2C+you+can+see+the+dogs+moving+around+and+barking%2C+medical+data+showed+they+were+calm+and+not+overly+stressed.%E2%80%9D&aqs=chrome..69i57.225j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

https://iz.ru/1049279/arsenii-zamostianov/sobachia-rabota-kak-belka-i-strelka-stali-geroiami-strany

https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/2015/06/26/dogs-in-space/

https://books.google.com/books?id=lOcnpwLXucEC

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20171027-the-stray-dogs-that-paved-the-way-to-the-stars

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24837199

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24837199

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20171027-the-stray-dogs-that-paved-the-way-to-the-stars

https://kulturologia.ru/blogs/271116/32401/

This is just brilliant. So informative and well written too. Thank you

My favorite story from the Soviet space dog program is the time a dog that had been training for months mysteriously vanished just before launch, so the dog handlers just caught a stray, cleaned it up, and launched it into space and it was just fine. Korolev only noticed the change upon the dog's return. IIRC, the code name given to the dog after the fact was Backup Researcher Bobik.