Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts in your email inbox.

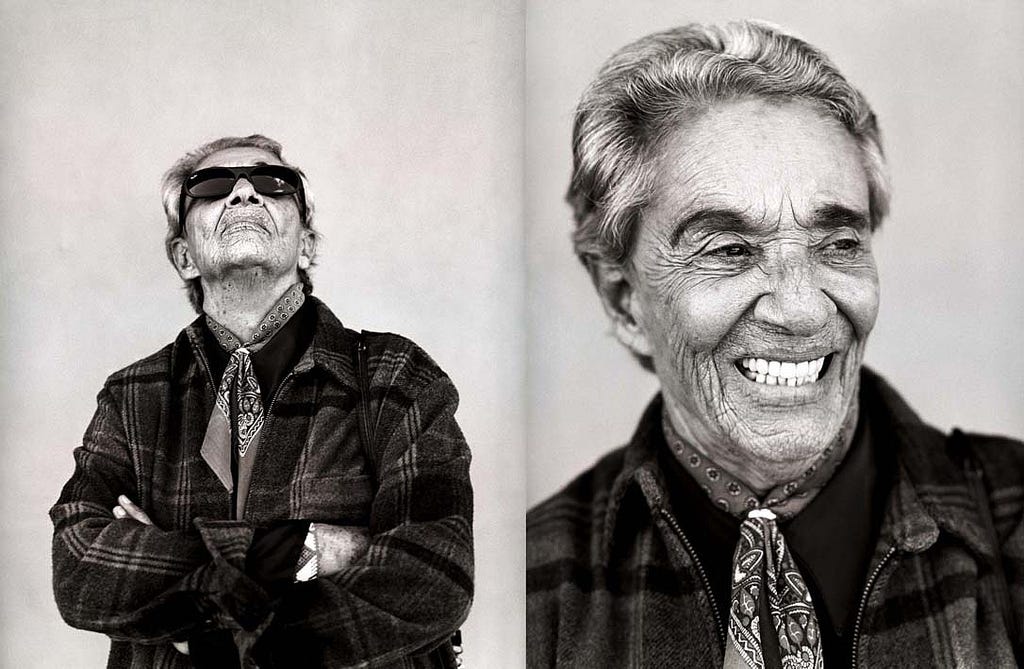

Chavela Vargas is one of the most influential voices in the history of Latin American music. She sang, and reimagined, boleros and rancheras—two genres traditionally performed by men. She transformed iconic songs by dispensing with mariachis and instead singing “from her gut,” to reveal the desolation that lived within the festive music. Director Pedro Almodovar remarked that “Chavela Vargas turned abandon and desolation into a cathedral within which we all fit.”1

In "Paloma Negra" ("Black Dove"), Chavela accuses a woman of partying all night long and breaking her heart.

Along the way to fame, she broke all of the gender stereotypes. As early as the 1940s, she refused to change the pronouns in traditional songs, addressing women as the object of her love. She smoked, drank too much, carried a gun, and dressed in pants, charro suits, sombreros, guayaberas, and ponchos when the other female performers of her time were restricted to dresses and high heels.

Her voice was as radical as her lifestyle. She’s been described as “la voz áspera de la ternura,” or “the rough voice of tenderness.” Here she is performing in the mid 1990s at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City for the first time in her 50 year career. She begins to sing at 1:10, after an brief introduction by director Pedro Almodovar, one of her biggest fans and close friends.

When she sings “Ponme la mano aquí, Macorina” she telling her love, a woman, to give her her hand.

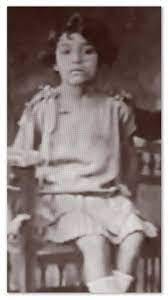

Chavela Vargas was born Isabel Vargas Lizano in Costa Rica in April, 1919. She had a difficult childhood. Her family was very religious, and “Chavela”—a pet name for Isabel—described them as prejudiced and fearful.

The singer has said she was “a very sad girl,” who was lonely as a child because she “didn’t have the love of her parents.” Chavela’s parents saw her as strange, a “niña-niño” with masculine movements, hands, and relationship to her body. One story recounts a priest kicking Chavela out of the church in front of everyone at the age of just seven for being a lesbian, and Chavela’s parents hiding her from visitors to the house like a “rabid dog.” “No one hugs me, no one even touches me,” she recalled. “Nobody looks at me, not even a frank look. That's my childhood.” Her own niece came to call her a “shitty lesbian.”2

By the age of 15, she was desperate to leave Costa Rica, and set her sights on Mexico. Chavela arrived with no money and spent more than a decade working as a street performer, slowly building her career and partying hard at nightclubs. She recalled the awkwardness of her early performances and trying to fit in:

In my first shows I appeared dressed as a woman, with long hair, makeup, earrings and heels. But it was absurd, I looked more like a transvestite. One time I was in a small theater and I had to go down the stairs to the stage, and I fell in front of the entire audience, because of my heels. It was a shame and a total failure.

Eduardo Barone wrote that this episode “marked the birth of the true Chavela Vargas, proud of her sexuality and her manly image.” Her fame began to grow, though she was prevented from performing at large theater venues in Mexico because she was a lesbian until she was more than 70 years old.

“Llevar el nombre de lesbiana. No lo voy presumiendo, no lo voy pregonando, pero no lo niego.” // “I carry the name of lesbian. I'm not showing it off, I'm not proclaiming it, but I'm not denying it.”

Much like her appearance, her singing style was revolutionary. She eliminated the mariachi accompaniment when she performed ranchera music, singing onstage only with her own guitar. She sang “slowly, stretching out the lyrics so there was no mistaking their meaning.”

Chavela was eventually discovered by the singer-songwriter José Alfredo Jiménez on Avenida Insurgentes. He reportedly “rescued her from the streets and turned her into a professional artist.”3

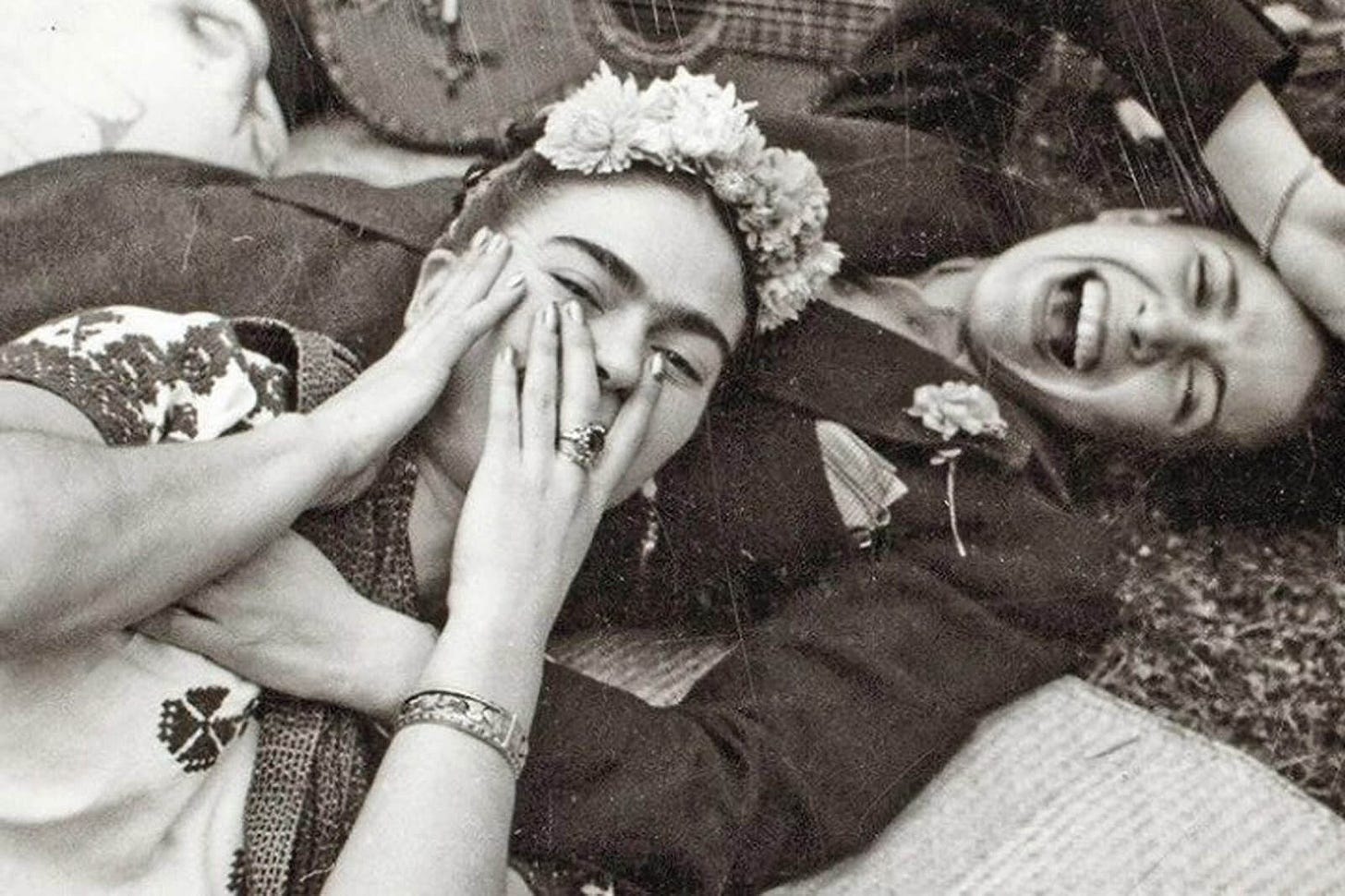

Then in the 1940s, she met Frida Kahlo, who was a dozen years older, at a party at La Casa Azul, Frida’s childhood home.

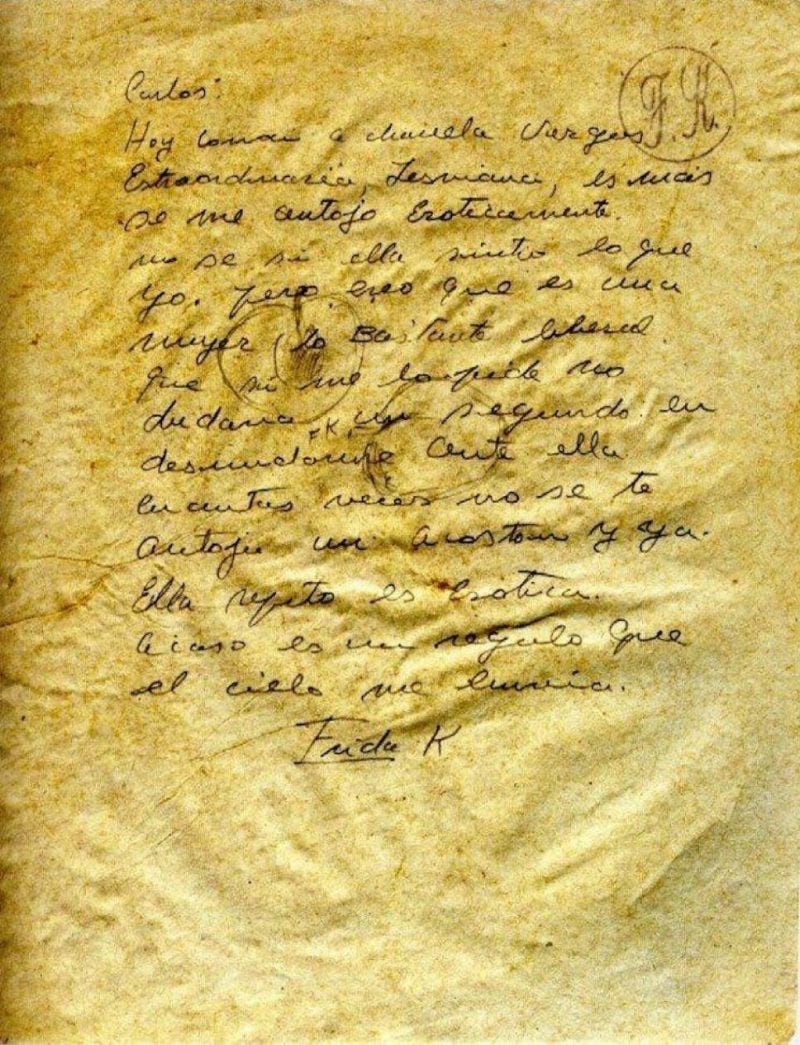

Although scholars wouldn’t confirm their romance for many years, recently discovered letters make their love hard to deny. Here’s a letter Frida sent the poet Carlos Pellicer after she first met Chavela:

Carlos:

Hoy conocí a Chavela Vargas. Extraordinaria, lesbiana, es más se me antojó eróticamente. No sé si ella sintió lo que yo pero creo que es una mujer lo bastante liberal que si me lo pide no dudaría un segundo en desnudarme ante ella. Cuántas veces no se te antoja un acostón y ya. Ella repito es erótica. ¿Acaso es un regalo que el cielo me envía?

Frida K.

//

Carlos:

Today I met Chavela Vargas. Extraordinary, lesbian, what’s more, I wanted her erotically. I don’t know if she felt what I did. But I think she’s a liberal enough woman, that if she asks me, I wouldn’t hesitate for a second to undress in front of her. How many times do you not want to get laid and that’s it? She, I repeat, is erotic. Is this a gift that heaven is sending me?

Frida K.

Soon after meeting, Chavela moved in with Frida at La Casa Azul for over a year, but it wouldn’t last. Chavela explained later in her life that the romance couldn’t work because she had to share Frida’s love with Diego Rivera. As Chavela recounts it, “one day I opened the door and didn’t come back.”4 Even though Chavela would have many famed affairs (Ava Gardner, for one), at the end of her life she described Frida as mi gran amor or “my greatest love.”

In an interview between Chavela Vargas and composer Elliot Goldenthal, the singer said that when she left Frida, Frida asked that she always remember her.

She appears to have kept her promise.

Soon after their break up, Chavela recorded one of the most hauntingly beautiful renditions of the Mexican folk song La Llorona ever realized, which she dedicated to Frida. Chavela howls the lyrics: “Si ya te he dado mi vida Llorona. ¿Que mas quieres? ¡¿Quieres mas!?...” (“If I have already given you my life, weeping woman. What else do you want? Do you want more!?...”) She would perform this song over and over again for the next fifty years.

In addition to the many performances of this song, there was another way that Chavela kept Frida close.

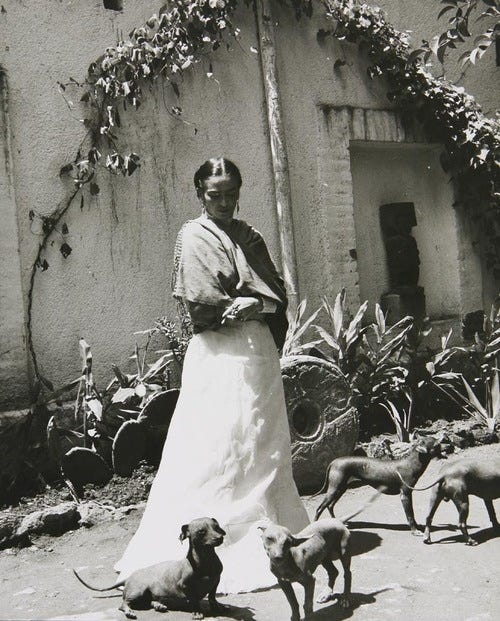

In the middle of the century, Frida had numerous dogs from a very specific and rare breed: xoloitzcuintles, or xolos for short. Xoloitzcuintles developed by natural selection, not breeding, over thousands of years, making them immune to human aesthetic engineering and interference. (Much like Frida and Chavela)

Bones of xolos have been found among 3,500-year-old Toltec and Maya burial sites. The indigenous people of Mexico believed that these dogs safeguarded homes from evil spirits, and buried xolos with their masters in order to guide their souls through the journey to the underworld.

The breed had neared extinction in the 1950s, when Frida got hers, but ownership of them has undergone a “renaissance” since. (Yes, Frida painted her xolos.)

Frida’s xolos accompanied her as she fell deeper into illness and ultimately transitioned into the afterlife, on July 13, 1954 at the age of 47 years, in her hometown of Coyoacán in Mexico City.

As Frida was falling ill with her xolos, Chavela descended into an extended period of severe alcoholism. She disappeared completely from the public eye after breaking down while performing La Llorona in Spain in the early 1970s. Chavela couldn't handle her shame and left the stage, and with it, popular life.

For fifteen years, Chavela withdrew so completely that many believed she had died. (At a concert in Mexico, one singer, Mercedes Sosa, announced that she wanted to take flowers to the cemetery where Chavela was buried to honor her. Chavela was still alive.) As Chavela recalled: “I disappeared from the stages and from everywhere. But before I disappeared from myself, that was the greatest pain. God couldn't find me, I wasn't anywhere..."5

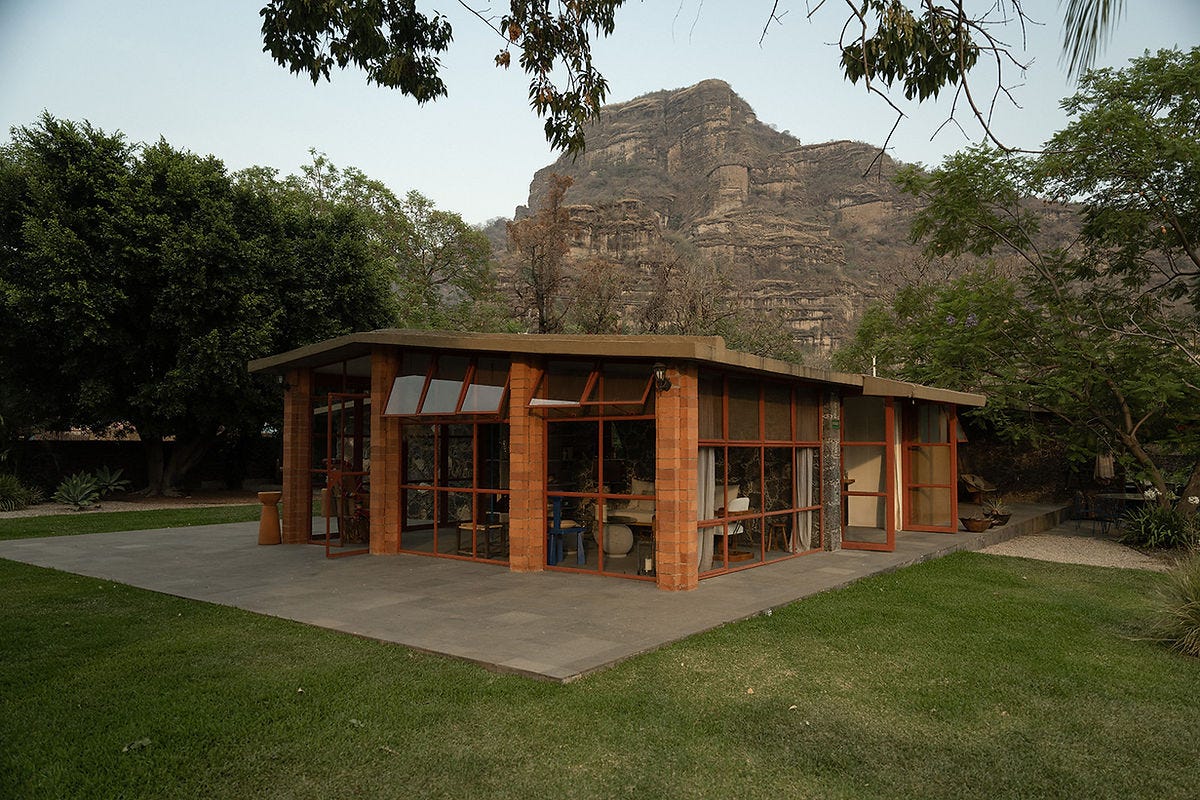

During this period, Chavela was living in southern Mexico City in an area called Tepoztlán. She described Tepoztlán as both her “her hell and her heaven” because the environment appealed so deeply to her mysticism. For Chavela, Tepoztlán was a magical place with “nights full of stars” where she could be close to “the power and magic of Tepozteco,” the local people who she later claimed healed her alcoholism.6

After a period of sobriety and subsequent resurgence in the 1990s and early 2000s, in which she traveled around the world performing, it was in Tepoztlán that Chavela spent her final years, preparing for the afterlife with xolos of her own.

Here’s a description of Chavela’s final years in Tepoztlán.

She watches the days go by, looking at Chalchi, a rock that rises behind a simple and bright house, surrounded by a beautiful garden. From time to time, a friend comes to visit her, not many. “I value quality more than quantity.” The rest of the time she enjoys her solitude, her dogs Lola7, Joaquín and Toby, the silence that she says she breaks when talking to those who left before. And she feels, reads, dreams. “I'm starting to live another life, without leaving mine.”8

Today, Chavela’s remains rest in the soil of the Chalchitépetl (Chalchi) foothills near her house, forever held by Mexico, her chosen country. Let’s hope her xolos, and Frida’s, brought them to the afterlife safely. Perhaps they found each other there—two great artist’s free in death and life from society’s chains.

At Chavela’s funeral, hundreds sang the great musician into the afterlife, lending their voices to a rendition of La Llorona led by three of Chavela’s musicial inheritors: Lila Downs, Eugenia León, and Tania Libertad. When I watch this send off and remember how her life started—a “niña-niño” rejected by her family, community, and country—it hits me deep in my queer heart. Chavela may be gone from this world, but she is lonely no more

"Así me voy a morir, libre, sin yugos" / "This is how I am going to die, free, without yokes"

Bonus

Before Chavela’s death but after her sobriety and return to the stage, director Julie Taymor asked Chavela to take part in her 2002 film Frida. You can see the singer singing La Llorona to Frida, played by Selma Hayek, in the scene below.

And here is Chavela singing La Llorona for the last time three weeks before her death in 2012. This concert in Madrid was “the last thing she wanted to do before dying.”

Note: Much of what we know about Chavela comes from a fantastic documentary about her, which was released in 2017 and you can watch online.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/aug/12/chavela-vargas

https://www.casachavela.com/chavela-en-tepoztl%C3%A1n

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2012/08/120805_chavela_vargas_semblanza_jgc

https://mexicodailypost.com/2020/12/04/romance-between-frida-kahlo-and-chavela-vargas-gets-renewed-attention-as-long-lost-love-letters-are-uncovered/

https://www.casachavela.com/chavela-en-tepoztl%C3%A1n

https://www.casachavela.com/chavela-en-tepoztl%C3%A1n

I bet Lola was named after Lola Beltran:

https://mariaverza.wordpress.com/2013/08/05/chavela-ve-y-diles-a-todos-que-no-me-ire/

THIS. This is why substack is on the leading edge currently. What an amazing amazing story. Thank you for sharing this!

my god. 🙏