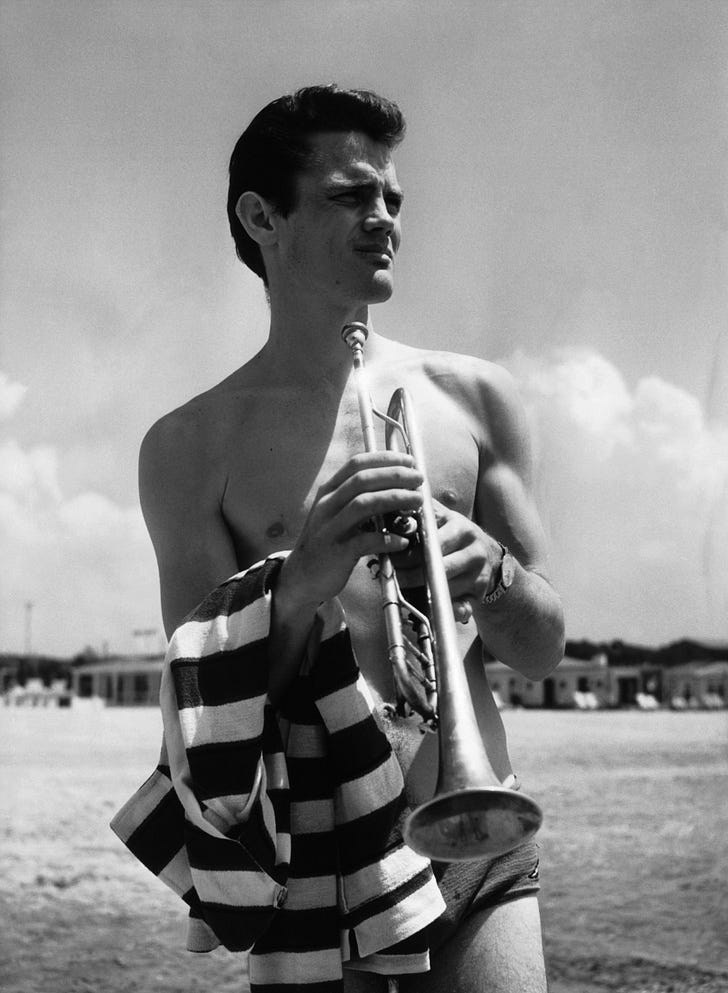

Chet Baker was an American jazz trumpeter and vocalist.

He was born in Yale, Oklahoma, in 1929 to two musician parents. As a young teenager in the 1940s, he served in World War II in Berlin, where he first encountered modern jazz by listening to Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Kenton. When he returned to the United States, he went to study music, and by the 1950s he was performing with the likes of Stan Getz and Charlie Parker. His style was described as “cool jazz,” characterized by relaxed tempos and tone.

In 1957, Chet began using heroin, which would lead to a string of arrests and progressive physical decline. The stories of his addiction are gnarly.

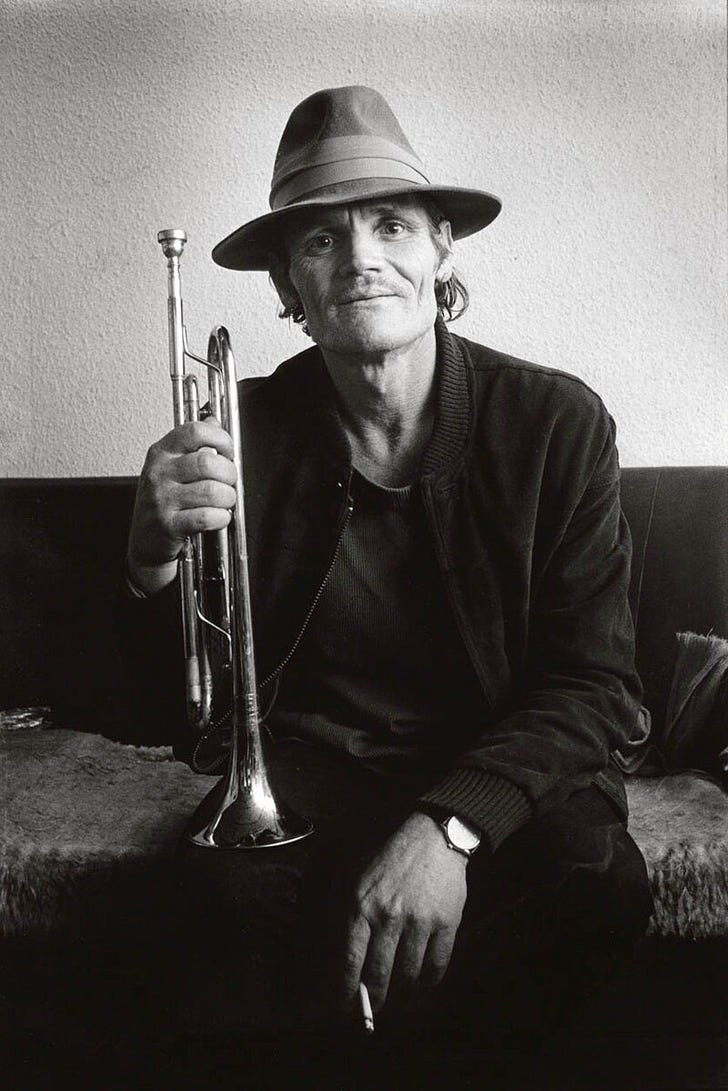

By the late 1960s, Chet “couldn’t play unless he was high” and his band and groupies would give him heroin, opium, morphine and cocaine to get him to go on stage.1 He was injecting himself 40 to 50 times a day, and “walking around in a fog.” “I lived in a nightmare of eternal anguish, existing from one injection to the other,” Baker once said. Jeffrey St. Clair wrote, “His arms and legs were covered with open sores and abscesses. His pants and shirtsleeves were often stained with blood. He disliked bathing and slathered himself in Paco Rabanne cologne to hide the stench.”

The creases on his face “multiplied and deepened” at too young an age and “his lips turned in over the dentures he had worn since his teeth were knocked out by angry dealers in San Francisco.”2 The dentures ruined his embouchure, and for three years he struggled to relearn how to play the trumpet and flugelhorn.3 Chet claims that he worked at a gas station during this time until concluding that he had to find a way back to music.4 (He eventually returned to touring, and would perform until his death in the late 1980s.)

Sadly, Chet Baker’s Art Dog story—like the musician’s own life story—will not have a happy ending.

In the 1950s, when Chet was beginning to use heroin, he briefly owned a dog.

A radio documentary about his life reported that at one point Chet grew tired of this dog, and simply left her behind in a hotel room when he was on tour in the midwest.5 Chet the drug addict could only muster enough energy to look out for himself. Not even a dog’s companionship was sustainable.

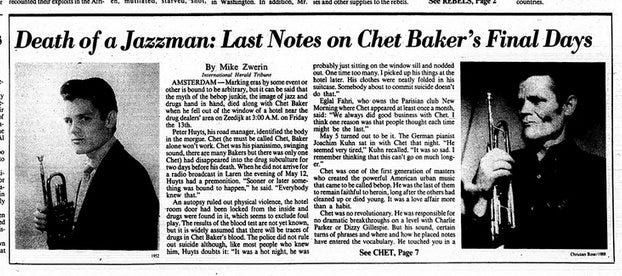

Perhaps it was karma from this mistreated border collie that later came back to exact revenge on Chet. In 1988, while staying at a hotel in Amsterdam, Chet left his friends to go upstairs and get some cigarettes from his room. He had locked himself out of his hotel room, but he noticed that the door to the room next door was open. Chet went into the neighboring room, walked out onto the balcony and tried to climb over into his room. He lost his footing, fell and died.

Given the depth of his addiction, it’s frankly amazing that Chet Baker lived to be 58 years old. My uncle had a much milder heroin addiction, and by his thirties he overdosed. He spent the rest of his life mute and paralyzed. The images of my Uncle Scott so incapacitated by heroin—unable to tell any of his three daughters happy birthday or pick them up at school, let alone walk himself up the stairs or take himself for a shower—are vivid elements of my childhood memories.

Meanwhile, heroin-riddled Chet Baker jetsetted to Asia and Europe, performing alongside the world’s best jazz musicians. Jeffrey St. Clair writes about Chet:

[Chet’s] music remained fixed in time, never evolving. His style, as hauntingly beautiful as it sometimes was, became a relic within a couple of years of those first recordings in Los Angeles. But his life had jumped the system. Baker breached every rule, transgressed every social convention, squandered every friendship, betrayed every intimacy. He negotiated a knife-edge for 30 years. He was a real outsider, a social reprobate, living without shame or remorse, bound only by the burning chain of his addiction. “My home,” Baker said, “is in my left arm.”

Chet’s ability to endure and create music for so long despite such all-consuming addictions makes him one of the luckier ones. I guess the irony of Chet’s life is that although he mostly took from the people (and animals) closest to him, he also had so much to give to us—the people who enjoy his music, but didn’t have to know him or rely on him in real life.

Alas, this relationship pattern seems to apply to so many great artists and great minds—taking so much from friends and family to be able to give to strangers. I wish that wasn’t the case, but perhaps for some artists it has to be this way. As Marina Abramović—another artist who made a pet dog suffer in the name of art6—asserted in her 2011 manifesto, “An Artist’s Life,” suffering may be innate to art making:

#3 An artist’s relation to suffering:

– An artist should suffer

– From the suffering comes the best work

– Suffering brings transformation

– Through the suffering an artist transcends their spirit

– Through the suffering an artist transcends their spirit

– Through the suffering an artist transcends their spirit

https://www.counterpunch.org/2011/11/25/scenes-from-the-life-of-chet-baker/

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/10/14/arts/international/iht-mike-zwerin.html

Valk, Jeroen de (2000). Chet Baker: His Life and Music. Berkeley Hills Books. ISBN 9789463381987.

rendarte piaz (1980). Chet Baker interview about drug and jazz1980 (in Italian). YouTube. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

https://canlit.ca/article/chet-bakers-dog/

Here’s what Marina had to say: “I tried to have the marriage life, but it didn’t really work. I always felt guilty that I worked and traveled too much. Now I’m getting to 70, and I’ve never felt better. I don’t need to tell anybody if I’m coming home or not. I can do whatever the hell I want. I didn’t want children because I didn’t want them to suffer. I had a dog, which suffered enough. I don’t even want a goldfish or a turtle. I have a desert plant in my house that needs a glass of water maybe once a year, which I can deliver. If you’re in a relationship, your energy is divided. If you have children, it’s even more divided. When I’m alone, there’s nothing else, so then I put in not just 100% but 20% more than 100%, and that 20% really makes it.”

You always go so in depth and share so much richness in these essays. Thank you.

Such a wonderful issue, once more.

As an aside, while I have tremendous respect for Ms. Abramovic, I find this part of the manifesto a fatalist bit of poppycock and toxic myth-making. Not to say that suffering cannot be turned into great art, like any emotionally intense experience (even happiness!), the way it's being formulated here and often is repeated leads to the misunderstanding that ONLY suffering leads to great art, which is of course not true. So much great art celebrates, overjoys, punctuates in positivity. It's the "should" in the "artist should suffer" that is the culprit here. The artist is a human, and while we all suffer at one point, we should not aim to suffer, and certainly not for art. <3