Constantin Brâncuși's "Polaire"

“What is real is not the external form, but the essence of things.”

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

In the early 20th century, Paris attracted a cadre of tremendous artistic immigrants. Pablo Picasso from Barcelona. Gertrude Stein from America. Amadeo Modigliani from Italy. James Joyce from Ireland. Marc Chagall from Russia. Diego Rivera from Mexico. These artists, and more, made personal pilgrimages to the City of Lights.

Of all these “great migrations,” perhaps none was more extraordinary than that of Constantin Brâncuși, the most influential sculptor of the 20th century.

Constantin Brâncuși was born in 1876 to two Romanian peasants. The family lived in a rural town near the Carpathian Mountains, a region known for its folk arts and woodcarving.1 Seven-year-old Constantin helped his family by herding sheep and showed early signs of talent in woodworking.

When he was 9 years old, Constantin ran away from home, fleeing abuse from his father and brothers. He found his way to a larger town nearby where, without a family to support him, he worked at a grocery. Later, he became a domestic servant. All the while, he continued making things with his hands. At the age of 18, a violin he crafted using found materials caught the eye of a wealthy man who in turn offered to pay for Constantin to study at the local Craiova School of Arts and Crafts. It was there that he finally learned to read and write.2

Emboldened by his artistic training, Constantin Brâncuși set off on an artist’s pilgrimage to Paris in May 1904. He hiked from Romania through Austria and Germany, reaching Paris in July.3 Constantin "immediately fell in with fellow artists,” and was invited to study in the workshop of Auguste Rodin. It’s said that after leaving Rodin's workshop, Constantin Brâncuși began to develop his own revolutionary style.

Unlike classical sculptures, which carved out idealized bodies in precise detail, Constantin Brâncuși’s modern works evoked the essence of objects. “What is real is not the external form,” he said, “but the essence of things.”

Let’s take a look at some of his artworks, with some music from the era if you feel so inclined.

From 1910–18, Brâncuși created a series of about thirty sculptures of birds. The word maïastra means “master” or “chief” in Romanian, and refers to a "magically beneficent, dazzlingly plumed bird in Romanian folklore."

Curator Carolyn Lanchner observed in a guide to MoMA’s Brâncuși collection that the artist had extraordinary “visual mnemonics,” which I found to be a perfect descriptive phrase. “A flash of recognition converts this elegant abstract sculpture into a likeness of the king of the barnyard,” she wrote of “The Cock.”4

I worked at SFMOMA just after graduating from college, and this piece is in their collection. It made me fall in love with Constantin Brâncuși. I saw a playful goldfish hiding in the portrait, and hints of the polished, over-perfect forms that Jeff Koons later made uber famous.

Brâncuși returned to fish and bird forms repeatedly to feed a deeper interest in the study of movement. He made seven fish sculptures (see more), remarking “'When you see a fish, you do not think of its scales, do you? You think of its speed, its floating, flashing body seen through water…Well, I've tried to express just that. If I made fins and eyes and scales, I would arrest its movement and hold you by a pattern, or a shape of reality. I want just the flash of its spirit.”5

![L'Oiseau dans l'espace [Bird in space], c.1931-36, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Constantin Brancusi. ADAGP/Copyright Agency.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!i4Fz!,w_526,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa1c489b9-5158-45f6-86bb-0fa653325fde_1600x2133.png)

Many art historians believe that Brâncuși’s most influential sculpture was his “Bird in Space” (1923 – 1940) form. Sixteen versions of the piece, made from either bronze, marble or plaster, exist in collections around the world. Although there are so many versions, each Bird is unique. “I never make reproductions,” Brâncuși explained; each sculpture is “a separate work made years apart. . . . If I change one dimension an inch all the other proportions have to be changed, and it is the devil’s job to do it.”6 The artist long advocated for “doing as much as possible with his own hands,” believing that the fine touches that transformed his sculptures must begin and end with his own touch, a perspective that was instilled in him as a young cabinet maker in Romania.7

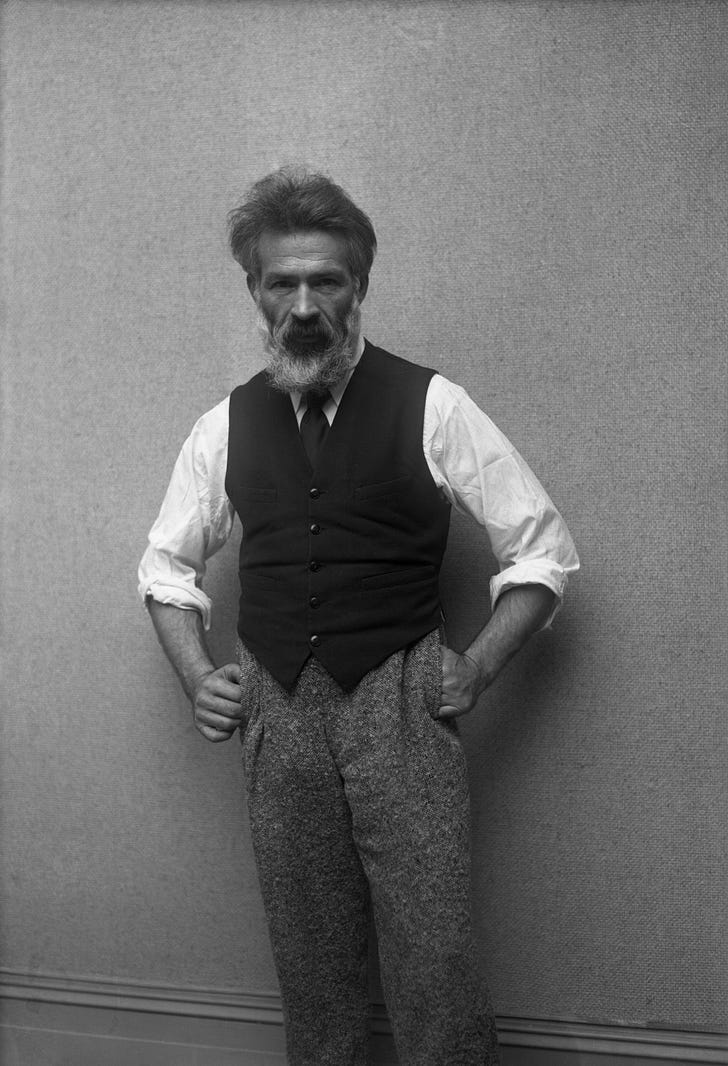

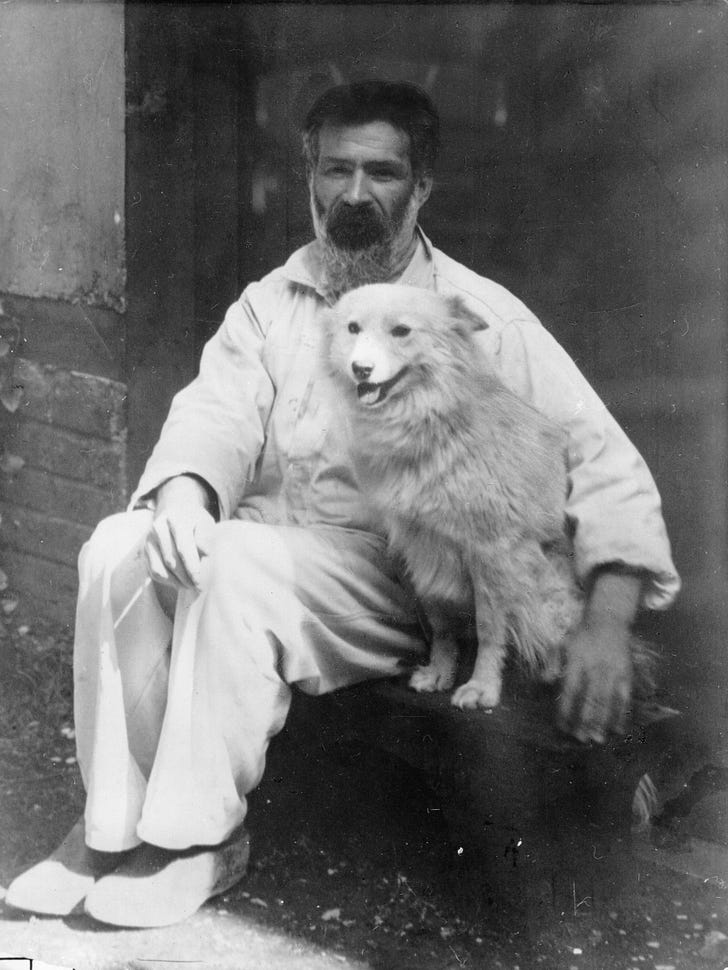

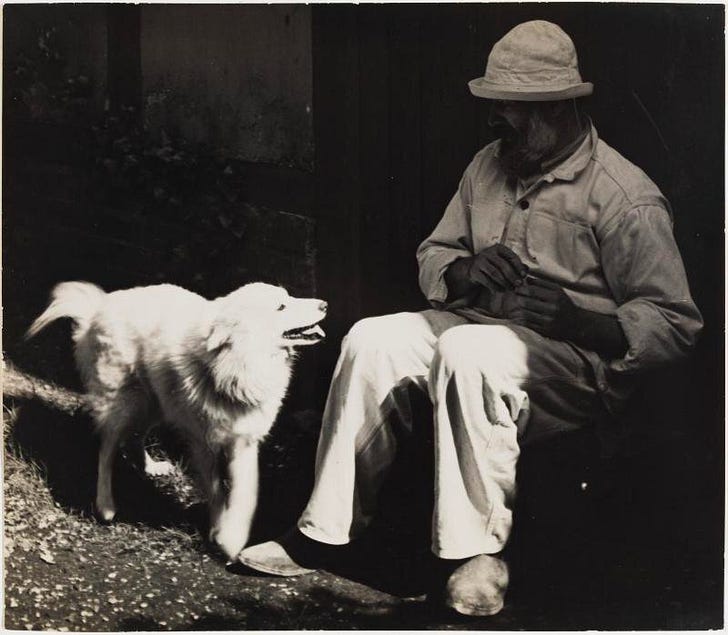

In the early 1920s, as his style, social life, and career took off, Constantin Brâncuși bought a Samoyed named Polaire. In The Studio Reader: On the Space of Artists, scholar Jon Wood observes that in French, polaire means both “polar,” like the bear, and is a shorthand for l’étoile Polaire, or “the North Star.” The dog seemed to offer the immigrant artist’s life such a guiding orientation.

Constantin and Polaire became fixtures on the Parisian art scene. The artist took Polaire with him to cafés, theaters, and even to the movies. “She became, in her own way, a celebrated Parisian beauty and friends would ask after her in their letters,” writes artist and historian John Golding in Vision of the Modern.8

During her lifetime, Polaire was photographed by Man Ray and captured in self-portraits by Brâncuși, sometimes even placing her on a pedestal like one of his sculptures.

Though it’s hard to confirm when, we know that Polaire died suddenly after being struck by a car, which left the artist in despair. Historian John Golding wrote that “Brâncuși was desolated.” He buried her in a pet cemetery at Asnières-sur-Seine, just outside of Paris, and returned to work. Golding notes that for the latter part of Brâncuși’s career, “depictions of animals far outnumber those of people.”9

Brâncuși never replaced Polaire with another companion, dog or human, and became increasingly reclusive. By the late 1930s, “the once gregarious socialite” had become “a hermit.” Because Brâncuși turned so deeply inward, the reason for this change in disposition remains unknown.10 He may have never explained or shared his emotional experience with anyone.

In 1956, a journalist for Life magazine wrote: "Wearing white pajamas and a yellow gnomelike cap, Brâncuși today hobbles about his studio tenderly caring for and communing with the silent host of fish birds, heads, and endless columns which he created."11 And the poet William Carlos Williams described how Brâncuși came to resemble Polaire in his solitary later years:

“The man, now well over 70, living alone…has now become famous for his broiled steaks cooked by himself at his own fire, which he himself serves as though he were a shepherd at night on one of his native hillsides under the stars. A white collie named Polaire used to be his constant companion reinforcing the impression of a shepherd, which, with his shaggy head of hair, broad shoulders and habitual reserve, he seemed to his friends to be.”

A pair of Romanian refugees who had moved in next to Brâncuși’s studio took care of him in his final years. In order to make these caregivers his heirs—a part of the artist’s story that I find particularly poignant, given his sculptures now fetch upwards of $20 million—he finally became a French citizen in 1952. He also bequeathed his studio and its contents to the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris before he died on March 16, 1957, at the age of 81, so that today all of us can stand where he and Polaire once roamed.

In 1977, on the piazza opposite the Centre Pompidou, the French built an exact reconstruction of Brâncuși’s atelier to house his collection, consisting of 137 sculptures, 87 bases, 41 drawings, two paintings and over 1,600 glass photographic plates and original prints. After a flood in the 1990s, Renzo Piano designed a new space to house the atelier, which you can go see today.

Constantin Brâncuși once said: “My life has been a succession of marvelous events.” One blogger responded to that statement with a reflection I enjoyed: “Whether or not this was really so, Brâncuși had the gift of seeing the marvelous in everything, a gift which he used to transform even the most mundane objects into ones that inspire a purifying sense of awe. With his gleaming, seemingly weightless heads, soaring birds, and columns, he revolutionized sculpture and invented visual modernism… [His works] are at once mysterious and revelatory, concrete and ethereal, simple and sublime; they force us, too, to see the marvel that is inherent in everything.”

In the documentary below, Carl Andre, Lynda Benglis, Ellsworth Kelly, Martin Puryear, Richard Serra, and more all speak to the influence Constantin Brâncuși had on their work. It’s well worth a watch, and as we do, to meditate on how this boy overcame destitute rural poverty, and a youth as a runaway art student, to become one of the most consequential artists of our time. Perhaps only a man who had been born into such poverty could create forms that say so much through so little.

Macholz, Kaitlin (July 20, 2018). "How Constantin Brancusi Brazenly Redefined Sculpture". Artsy. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

https://web.archive.org/web/20061220115258/http://www.brain-juice.com/cgi-bin/show_bio.cgi?p_id=108

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2004/jan/03/1

https://www.nybooks.com/online/2018/07/28/the-ascetic-beauty-of-brancusi/?lp_txn_id=1495260

Malvina Hoffman, Sculpture Inside and Out, New York 1939, p.52

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81503

https://www.ideelart.com/magazine/brancusi-bird-in-space

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-brancusis-beloved-dog-influenced-art

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-brancusis-beloved-dog-influenced-art

https://web.archive.org/web/20061220115258/http://www.brain-juice.com/cgi-bin/show_bio.cgi?p_id=108

https://web.archive.org/web/20061220115258/http://www.brain-juice.com/cgi-bin/show_bio.cgi?p_id=108

I can hear the affection in your words, Bailey. What a wonderful post. His sculptures have always appealed to my eye but I knew nothing about his extraordinary background and personal life. And his dog, Polaire! What a sweetie.

Wow, what a story!!