Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

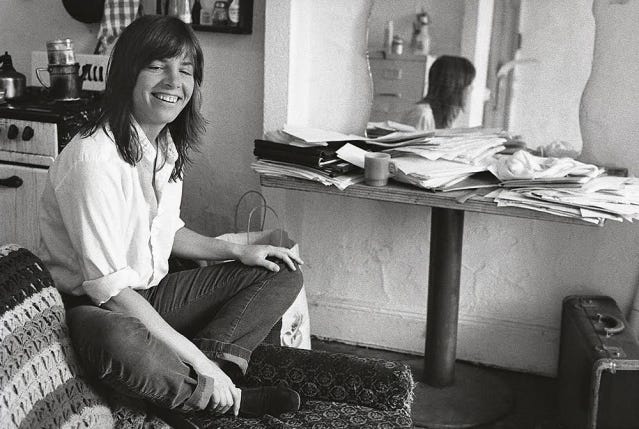

For four decades, Eileen Myles has been a mainstay of New York's poetry scene. Author Ben Lerner noted in his wonderful interview with Eileen Myles in the Paris Review that “Myles is often referred to as an institution; the way one speaks of a terrific restaurant that’s endured the waves of gentrification.” In their career, they've authored 20 books, run for president, and won a Guggenheim Fellowship.

In recent years, they have been elevated into the status of a queer literary icon. Maggie Nelson once said that their work “is an object lesson in how literature, at its best, creates its own audience, rather than serving any existing god.” Millions saw their poems (as well as a character modeled after them) on their ex Joey Soloway's TV show Transparent. Shoshana Olidort wrote in 2018 that “Eileen Myles may be the closest thing we have to a celebrity poet.”

Despite this burst of fame, you can still find Eileen Myles participating in the young art scene in Marfa, frequenting the downtown New York galleries, reading their work in public, and… taking their dog to the park.

Eileen Myles was born in Boston to a working-class Catholic family. “The cliche about working-class families is that you’re violent and explosive and loud. We were not,” they recalled. “We were silent, imploding. Readers. And depressed. And then there was alcoholism.”1

When Eileen was 11, their father, a heavy drinker, fell from the roof in front of his kids “while trying to push a large piece of furniture that wouldn’t fit down the stairs out of an upstairs window.”2 Eileen later recalled the day of the accident in the Paris Review.

He woke almost instantly after he hit the ground—and went to the hospital. He had pounding headaches for the next two weeks, and he went for an EEG, but they had crappy instruments in 1961, and they sent him home. I was in school that day, in seventh grade, and there was going to be a party that night, the first girl-boy party I was allowed to go to. Junior-high sex. There was total excitement that day in school. I got in trouble for laughing as we were all going down the stairs, so the nun said, Eileen Myles, write “I will not talk in the corridors” five hundred times as punishment. It was like a prompt. Does Sister Ednata know how many poems she unleashed with that command? When I got home, my dad was taking a nap on the couch. My mother said, Why don’t you just set up a table in the den and do your punish task there so you can keep an eye on him. I’m going to go out and hang clothes. She’s in the yard and I’m writing “I will not talk in the corridors,” and he starts to make weird sounds and he died there right in front of me, his face changing colors and the death rattle and the whole thing and I just kept writing “I will not talk,” “I will not talk.” And then he’s dead.

Eileen was alone in the room with their father when he died, but for decades after, no one in the family ever spoke about the incident.3 That silence propelled Eileen’s life and art forward. As Emma Brockes later wrote in The Guardian, “It was a silence against which Myles has been writing.”

Eileen knew they wanted to be a poet by their early twenties, and moved to New York at 25 years old, in 1975 and not yet an out lesbian, to pursue that dream. It’s strange to read about their homophobia, given the confidence and assertiveness they sit in their identity with today.

When I came to New York in the 70s, I didn't know I was a lesbian. I didn't want to come out. I was homophobic, or scared—I just didn't want to be a dyke. There wasn't a woman in that circle of poets, either, who could receive me and let me know I was heard. . . . I made the model of what I needed there to be. I put lesbian content in the…poem because I wanted the poem to be there to receive me.4

In 1977, they moved into the apartment in the East Village that they still call home today. Eileen would go on to teach workshops out of their apartment, which some incredibly talented writers attended, including Maggie Nelson, who has said that she moved to New York as a young writer to be near Myles.5

Much like many other great artists in downtown New York at the time, Eileen has stories from the scene like running into Madonna bartending in the East Village before her fame. Myles remembers:

It was when every junkie in this neighborhood had the little crucifix earrings and Madonna saw that, put them on, went on MTV and went global. I think she’s a genius of the level of Warhol or Gertrude Stein. She knew what to touch; knew the platform she was on and used it, radically.

They spent much of their time at the Poetry Project in the East Village’s iconic Saint Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery. Myles would mingle with “poets drinking and smoking cigarettes around long tables in the church’s back rooms, at seminars run by Alice Notley and Ted Berrigan. Allen Ginsberg came to readings,” whom Myles came to know. And “the group’s leaders were heroes and the East Village felt, to Myles, like the center of anti-institutional American poetry.”6

Eileen Myles later captured this era in New York in their autobiographical novel Chelsea Girls (1994). Here’s The New York Times describing the novel:

[Myles] gets her amphetamines from a corrupt diet doctor in Flushing, Queens, and redistributes them at the Strand. She subsists on garlic knots, hot dogs, Campbell’s tomato soup, Budweiser and cigarettes. She has lovers of different temperaments and physical forms. One of them convenes an “elite junkie salon.” Another throws herself into the East River. Of a stint working a factory job in Maine: “The men were all men, and we were all lesbians, and everyone loved to get smashed.”7

Eileen got smashed, too. They would drink “until they fell down.” “I would hit my head a lot. I would wake up and have black eyes,” they explained to the Paris Review. “I was big for head injuries, which is how my dad died.”

Eileen finally gave up alcohol in 1980, at the age of 33, which they describe as “the great transformation” in their life. They have said that getting sober “rescued their writing,” because at the end of their drinking their writing “had gone to shit.” They told Ben Lerner that immediately upon getting sober, “I began to write better poems. It was like reorganizing my mind in some new way.” Their first major collection, Not Me, was published ten years later, in 1991, kickstarting their public success.

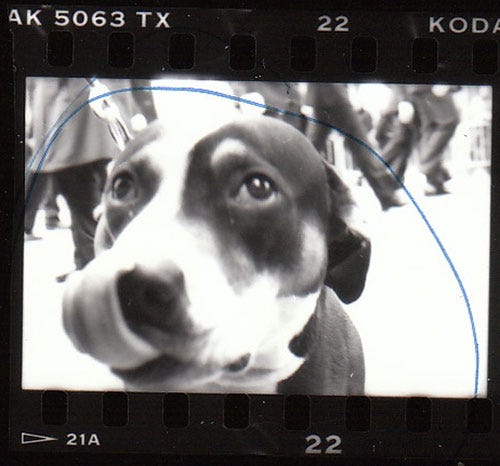

And it was just before this first major collection went to print that Rosie came into Eileen Myles’ life, the first dog the poet ever owned.

Eileen paid $50 for Rosie, and bought her off the streets of New York. “When I first got Rosie, I looked into her eyes and thought, This is my father,” they later reflected. “I was always obsessed with him. It was a joke I had for the sixteen years of Rosie’s life—that my father came back as my dog just to hang out a little more.”

Eileen Myles would write about Rosie, and dogs, throughout their career. And Rosie’s presence affected the nature of the poet’s writing. Myles has said: “[Rosie is] a camera. As soon as this dog was in my life there was this different level of focus, a whole kind of landscape I was brought into. And it stopped being as human-centric. The dog became me and the sky, me and the sea, me and the dirt, me and the city.”8

Here’s Eileen writing about what life with Rosie felt like. I found this writing as tender and true as any about the experience of co-existing with a dog:

With you everything got better. It got close. Or we could sit outside and look into the distance. Or I could just sit there, inside or out, and gaze at the parts of you. Your paws. So soft I’d rub my fingers against them, your hard round living mittens. Your pads, the underneath of your feet, were like delicate sneakers, hardy from walking barefoot all the time, but I had to also notice that I was wearing flip-flops now because the tar was so hot and you were alive and felt things too. Ouch. I loved how you loved snow. You’d bounce and smile and go crazy. You learned to swim so very old. Water made you young again, light. The green illumination went on in your eyes and you had everything back again. You liked the city, the garbage, the stink, the sidewalks covered in chicken bones, and French fries and an opera of smelly stuff and the country was so wild, and you just liked to run.

I don’t think you were a friend, you were more like dating life itself, meeting it head-on so every time I went into it with you, or if I was in my apartment, home alone or with someone else, you always threw us back on what we were doing and how we were doing because you needed us, and your stuff, your toys, your water, your food, your in and out and that was it and why was I ever suffering, why did I think life was so complicated when it was simply this. Us here now.

Sobriety and Rosie—Eileen’s father reincarnate—perhaps gave Eileen the stability that allowed for their creative genius to fully emerge. Eileen Myles told The Creative Independent about the architecture of their days:

I got up in the morning, drank coffee, took my dog for a run, and I meditated. It’s just like, “I have one habit.” And then I began to work. That’s the best me. That person can finish a book…there’s a ritual that I need in order to be the person who can complete things. The person who digs—the doggy character who digs up stuff and finds a bone. It’s all over the place. There are bones everywhere.

This base was essential because at the same moment as their poetry was gaining recognition, many of their friends and peers were dying of AIDs. “I lived through so much dying that it almost became commonplace. And I had Rosie through all of that time, too,” Myles told The Paris Review. “I’ve had her through the time of so many relationships that bloomed and failed. She’s the metonym for so much stuff.”9

It was in this moment of both personal creative momentum and deep grief that Eileen got political. Eileen became incensed while watching a commencement speech by President George H.W. Bush, in which he declared that political correctness had began as a “crusade for civility,” but had “soured into a cause of conflict and even censorship.” Eileen Myles felt that when Bush referred to the politically correct, he was actually referring to the queer community and to the marginalized, generally. As Myles wrote: “he means members of ACT-UP, victims of bias crimes: women, homosexuals, ethnic and racial minorities. He would like them to shut up.”10 The President wanted to silence them.

“It was silence against which Myles has been writing.” - Emma Brockes

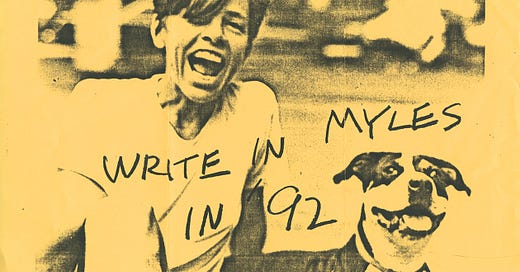

In response to this speech, at the age of 41, Eileen Myles launched an “openly female & queer” campaign for president of the United States, which they describe as “both dead serious and entirely ludicrous.” At the time, Eileen says “there wasn’t any possibility that there would be a female candidate, a gay candidate, an artist candidate, a candidate making under $50,000 a year, a minority candidate,” Eileen told

. “The thing I grew up with in American history—‘Taxation without representation is tyranny’—was the condition I was living in.”

Eileen turned every public event they were asked to take part in into a campaign opportunity. “If you asked me to do a poetry reading, if you asked me to be on a panel, if you asked me to speak at a memorial, whatever it was, I was going to run for office, and that would not end until November of 1992.”

Below, watch Eileen Myles perform American Poem, which was published in their first major collection, Not Me, in 1991. Maggie Nelson said that Eileen Myles’ performance of this poem “changed my life.” “[Eileen] had memorized it, and I remember it being really unnerving, to see someone perform that way, i.e. not theatrically, just looking at us squarely in her own body and reading her poem.”

The poem is centered around a ruse—that Eileen, a working-class, lesbian Bostoner, is in fact a member of the Kennedy family unbeknownst to their friends. It’s worth reading the entire poem and watching Eileen Myles perform it, but here’s an excerpt to taste it:

Listen, I have been educated.

I have learned about Western

Civilization. Do you know

what the message of Western

Civilization is? I am alone.

Am I alone tonight?

I don’t think so. Am I

the only one with bleeding gums

tonight. Am I the only

homosexual in this room

tonight. Am I the only

one whose friends have

died, are dying now.

And my art can’t

be supported until it is

gigantic, bigger than

everyone else’s, confirming

the audience’s feeling that they are

alone.

…

I am notalone tonight because

we are all Kennedys.

And I am your President.

If you listen to the piece in full, the poem may feel familiar to you.

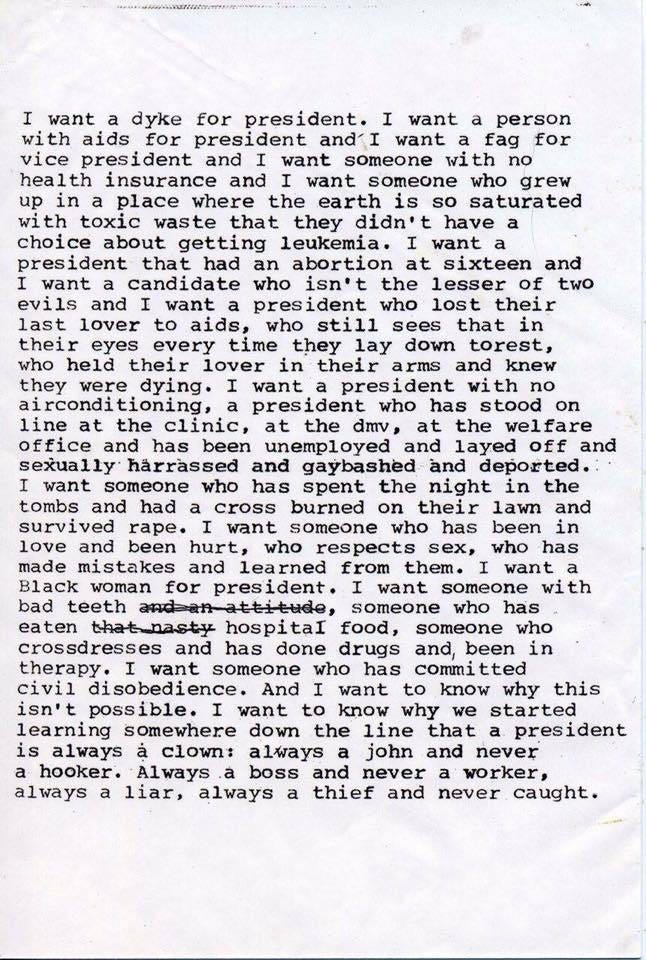

In 1992, the artist Zoe Leonard was inspired by Eileen Myles’ campaign. She and Eileen were friends, and Zoe had attended many of Eileen’s rallies and even wrote-in Eileen’s name in the primary. Zoe Leonard recalled standing in the crowd at Eileen’s rallies and being baffled asking herself:

“Why is this so outlandish to me? Why is this such an unbelievable, radical, crazy idea that everyone thinks is impossible? Why can I not believe that Eileen could be a president?”

So Zoe sat down and over the period of two days wrote a manifesto on a typewriter that starts “I want a dyke for president.” That dyke is Eileen Myles.

Zoe Leonard’s piece didn’t get published, but it gained recognition after being distributed amongst friends who photocopied and shared the work.

During the 2016 election, Zoe Leonard’s poem experienced a resurgence.

In October of 2016, a team pasted it as an enormous poster on Manhattan’s High Line. Then just two days after Donald Trump won the election, twelve writers and artists convened on the High Line to reflect on the text and its evolving meaning given the results.

Zoe Leonard asked Eileen Myles to speak, encouraging Eileen to act as if they had still been running for president today. The poet decided to write and perform an acceptance speech, which you can watch below (do it! the speech is really excellent and starts at 2:30) or read in full here.

To research this post, I watched a discussion between Eileen Myles and Zoe Leonard hosted by the Hirshhorn in 2021. The moderator asks Eileen if they knew that Zoe had been inspired by their poetry, and Eileen says yes—that as they understood it, they and Zoe were in a call-and-response dynamic, riffing with one another. Eileen then says to Zoe: “That’s the thing that’s so beautiful about art: every new, important piece makes space and makes possibility.”

That, to me, will be Eileen Myles’ greatest legacy. Their life and art unabashedly celebrated and served the otherwise silenced—silenced topics and silenced people. In doing so, they acted as a catalyst for other great artists like Maggie Nelson, and artworks, like “I want a dyke for president.” The artwork and ideas that cascaded out from Eileen Myles have tangibly expanded my own imagination of what my queer life and a more humane version of my country could look like. I’m sure I’m not the only one.

Rosie passed away in 2006 after a 16-year relationship with Eileen Myles. While Rosie was dying and her body was falling apart, Eileen Myles began to write—to inventory the experience the only way a poet knew how.

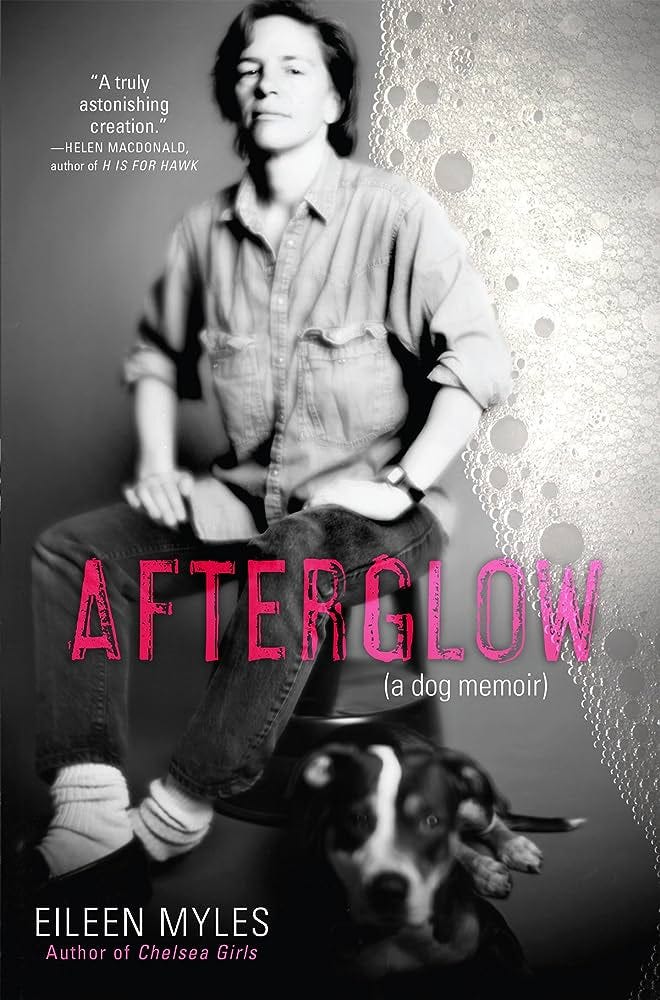

In 2012, Eileen Myles was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete a book about Rosie. In 2018, just two years after giving their presidential acceptance speech on the High Line, Eileen published Afterglow, a “dog memoir” about Rosie. Eileen eulogizes Rosie, details the grief of losing her, and also gives Rosie a voice in the book. (Rosie acts as a narrator in some chapters.)

In the book, Eileen Myles does for Rosie what they have done for many others whose realities are otherwise rendered invisible. As Michael Silverblatt describes the book:

“This is quality representation…wherever [Rosie] goes, she is given a special way of being seen and being described and being present, and that is what makes it Rosie’s book. The dog has the great good fortune of being given consciousness of every kind… This is the afterglow. She's alive after her death, and she is glowing.”

Quality representation sits at the heart of what Eileen Myles has offered to many of us.

Thank you, Eileen. I suspect your life will have its own afterglow.

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/16/eileen-myles-learn-to-write-poems

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/16/eileen-myles-learn-to-write-poems

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/16/eileen-myles-learn-to-write-poems

https://poetrysociety.org/poems-essays/tributes/maggie-nelson-on-eileen-myles

“I met Eileen before the internet, or at least before I used the internet; things were more on the line. I literally moved to NYC to find her body, her voice, to be near whatever it was that I saw and heard that night. It never occurred to me to get an MFA, because I had heard that Eileen taught workshops out of her apartment and others' apartments in NYC, so after graduating college that's where I angled myself.” - Maggie Nelson https://poetrysociety.org/poems-essays/tributes/maggie-nelson-on-eileen-myles

https://bridgetdonahue-media-w2.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/files/1oR3wOeGSQCJ7zZ0dTS3hg.pdf

https://bridgetdonahue-media-w2.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/files/1oR3wOeGSQCJ7zZ0dTS3hg.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/16/eileen-myles-learn-to-write-poems

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6401/the-art-of-poetry-no-99-eileen-myles

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/shining-a-light-on-eileen-myles#:~:text=In%201992%2C%20Eileen%20Myles%20lost,an%20act%20of%20political%20protest.

brave writing, Bailey 🙏🏼

I love Zoe Leonard and didn’t know her piece “I want a Dyke for President” was inspired by Eileen!