Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

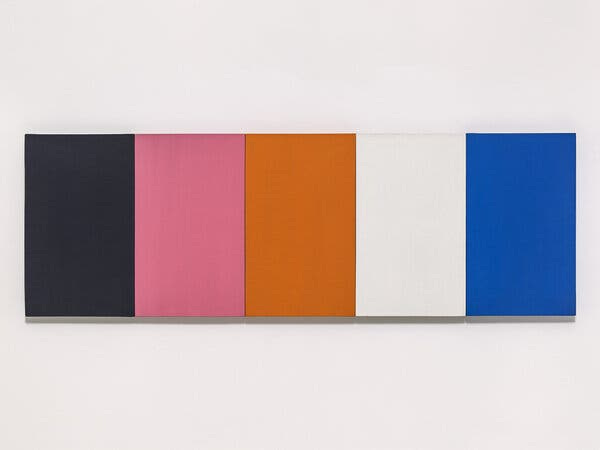

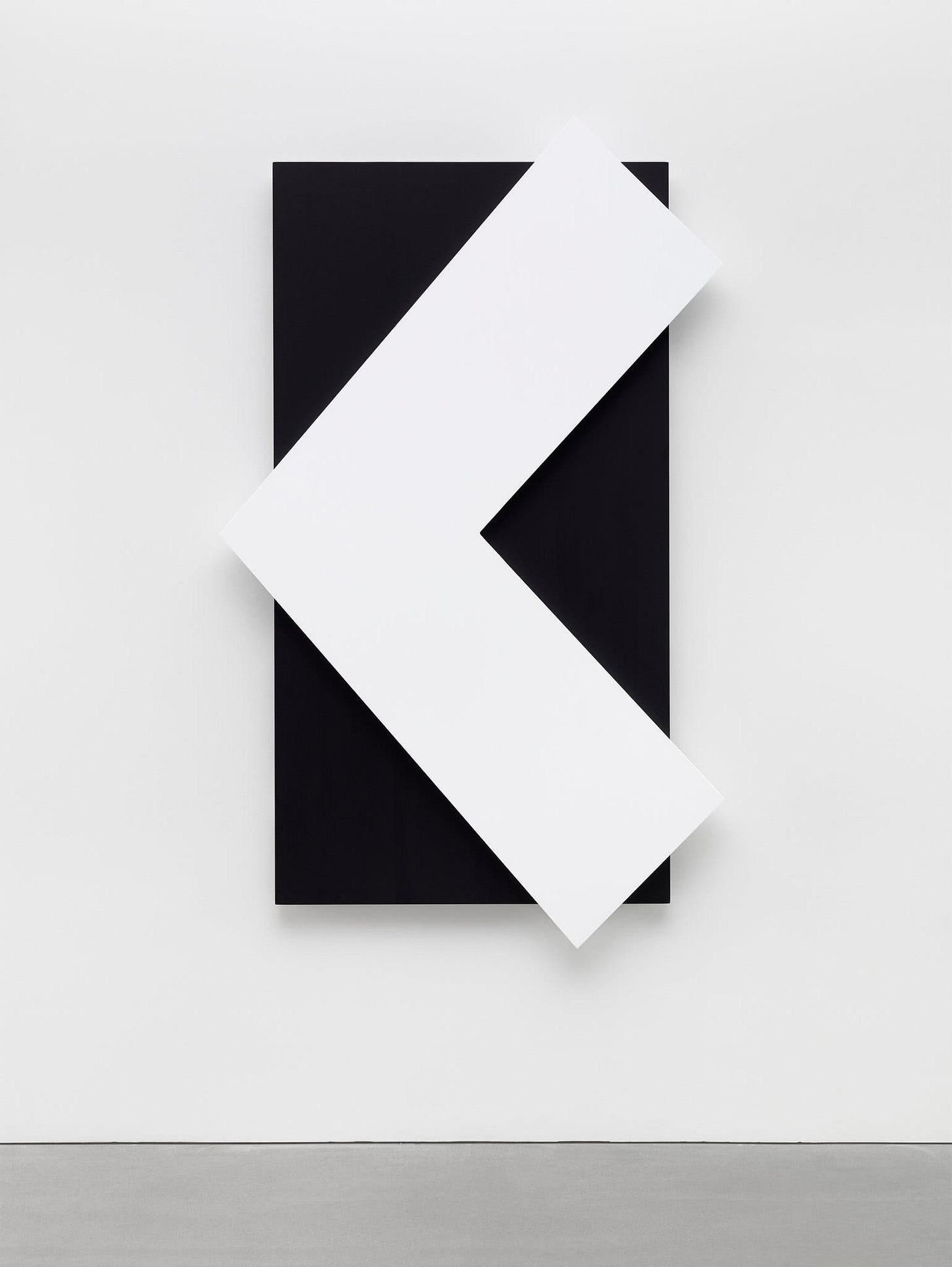

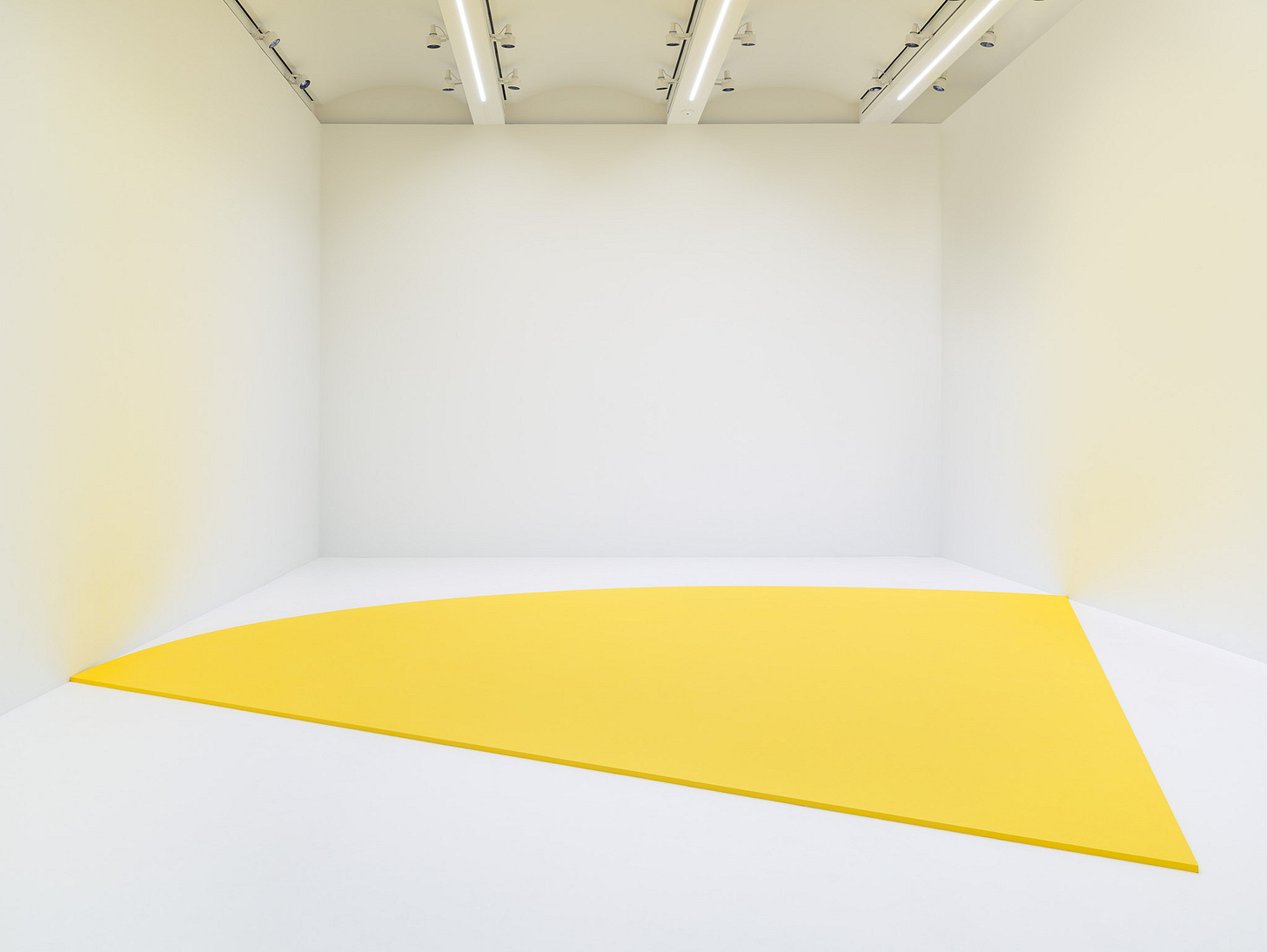

Ellsworth Kelly was an American abstract artist. As writer Jason Farago noted, “Few artists alive today have done so much to rethink the possibilities of painting. Even fewer have offered viewers such endless joy while doing so.” For more than 50 years, he created hard edged, brightly colored abstractions that lived on the borderline between painting and sculpture. Peter Schjeldahl wrote that Ellsworth Kelly’s artwork contained:

“the suddenness of miracles, and the improbability. Their emphatic shapes and clarion colors, in myriad formats, are unreasonably rational and ascetically luxuriant… You are on your own when you look at them. I think that their open secret is innocence, maintained at fantastic levels of talent, dedication, and savoir-faire.”

Today, the list of major museums that do not hold Ellsworth Kelly’s work in their collections is “miniscule.” His art has found its way to Rockefeller Center, Penn Station, and postage stamps. In 2012, he received a National Medal of Arts from Barack Obama. Three years later, he died at the age of 92, one of the last standing great American mid-century artists.

"Everything has presence…all spatial arrangements are pregnant with a kind of life substance." — Ellsworth Kelly

“The strength of Kelly's best work has always been its winning combination of perceptual subtlety and sensuous immediacy. It's this odd alliance of sweetness and might which has made Kelly such an awkward fit in the canon of American modernism.” — Simon Schama

“To hell with pictures - they should be the wall - even better - on the outside wall - of large buildings. Or stood up outside as billboards or a kind of modern "icon". We must make art like the Egyptians…with their relation to life. It should meet the eye direct” — Ellsworth Kelly, 'Letter to John Cage', September 4, 1950

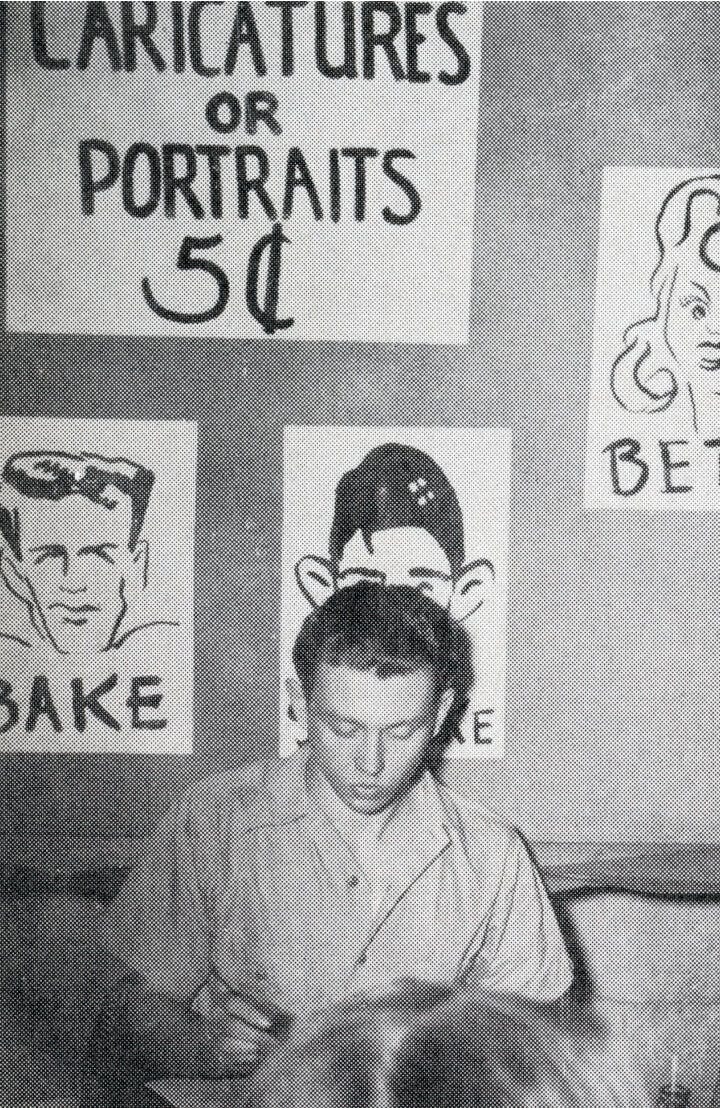

Ellsworth Kelly was born in Newburgh, New York, in 1923. As a very young boy, he showed creative instincts. Ellsworth Kelly shared in an interview that one day as a child, “I saw this pound of butter [the milkman left outside our door], and I stepped on it and flattened it. And here was this great yellow shape. That was my first painting.” He went on to say: “I’ve been flattening everything ever since.”

His family soon relocated to Oradell, New Jersey, where he and his grandmother, Rosenlieb, would birdwatch at a nearby reservoir.

In interviews, he often shared a memory of the first time he saw a Redstart, a small black bird with a few very bright red marks. (see below) “When I was six, my mother and grandmother bought me some bird books. I remember a little red and black bird in the pine forest behind my house,” he recalled. “It kept flitting ahead of me. I would follow it, and look at it, and it was magic.” He later explained in the introduction to his 2018 Phaidon monograph that “I believe my early interest in nature taught me how to ‘see.”

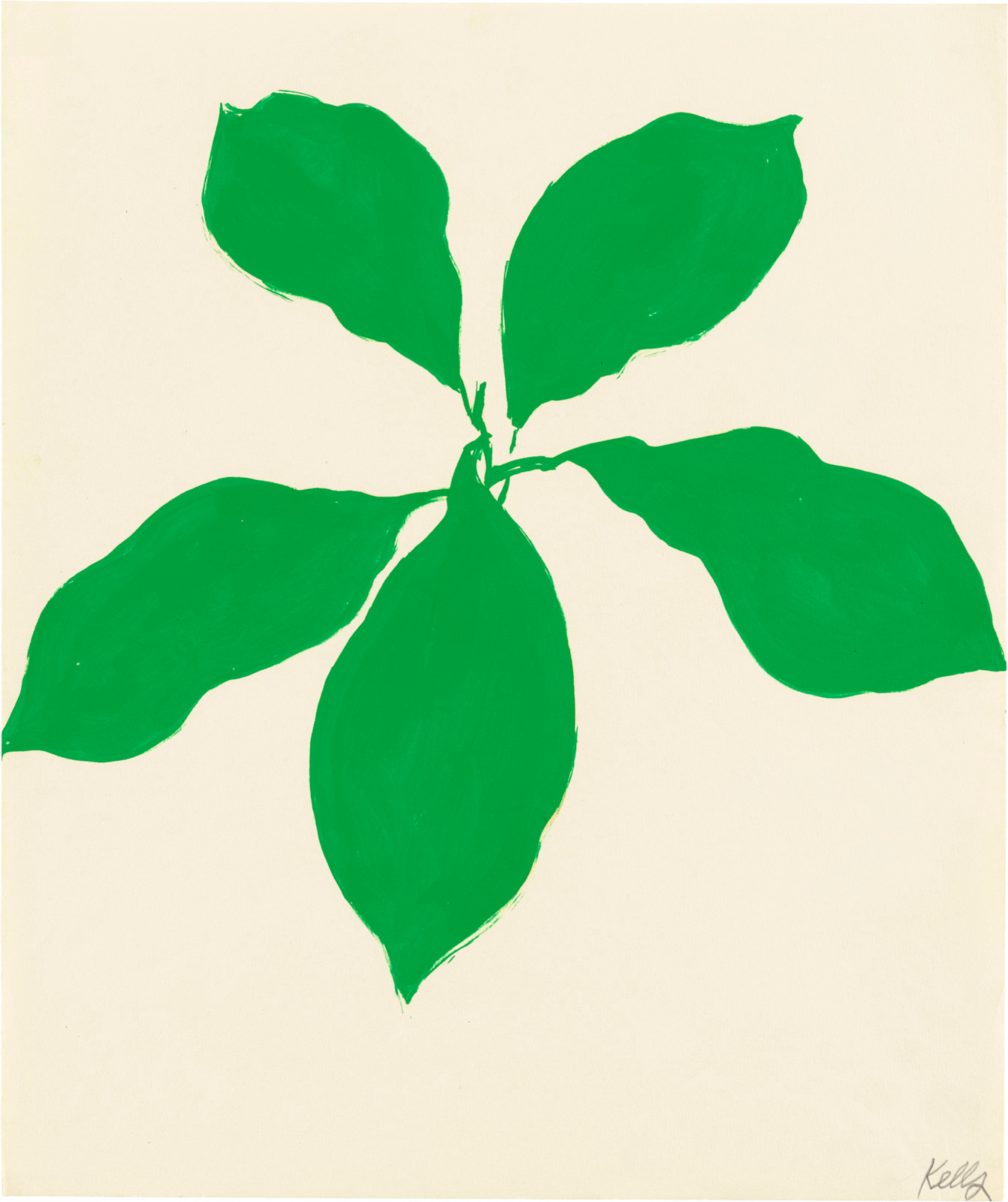

During periods when he was bedridden with illnesses as a kid, he poured over the detailed ornithological drawings of John James Audubon and Louis Aggasiz Fuertes. He learned the names, colors, and shapes of local birds by the age of eight or nine.1 “When I was a child,” he wrote in an essay in 1969, “I spent all my spare time looking at birds and insects. My color use […] and the use of fragmentation is closer to birds and beetles and fish than it is to De Stijl or the Constructivists.”2 Through watching the active, colorful creatures, he became interested in the relationship between color and space. “I delighted in color very early,” he recalled.

The impact of this passion for birding and observation would prove long lasting. Birdwatching remained one of Ellsworth Kelly’s lifelong hobbies, and the artist would say in interviews that “color fascinated [him] in birds—red streak here, blue streak there, green streak here.” MoMA wrote:

It is worth speculating that close acquaintance with the black-throated blue warbler and the red start and all the other two- and three-color birds is traceable in the two- and three-color paintings Kelly is best known for; and that as a kind of boy naturalist, out of doors all the time, almost constantly alone —he was, he says, a "loner" who did not talk early or very much and even had a mild stutter into his teens —Kelly's independent character, both as a person and as an artist, was formed well before puberty.

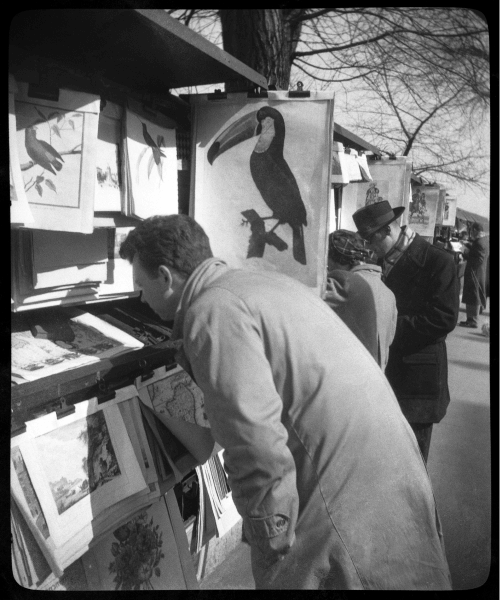

After stints studying art at Pratt, then being drafted in the military and shipping off to Europe in World War II, he returned to the United States in 1945 to resume his education, under the G.I. Bill. Later, he took a pilgrimage to Paris to further his studies, where he lived poorly, moving “from dingy hotel to dingy hotel.”3

Through the friends he met in Paris, and later the time he spent in the countryside of France, Kelly developed his own style. He described his evolution to The New York Times in 1996:

I realized I didn’t want to compose pictures. I wanted to find them. I felt that my vision was choosing things out there in the world and presenting them. To me the investigation of perception was of the greatest interest. There was so much to see, and it all looked fantastic to me.

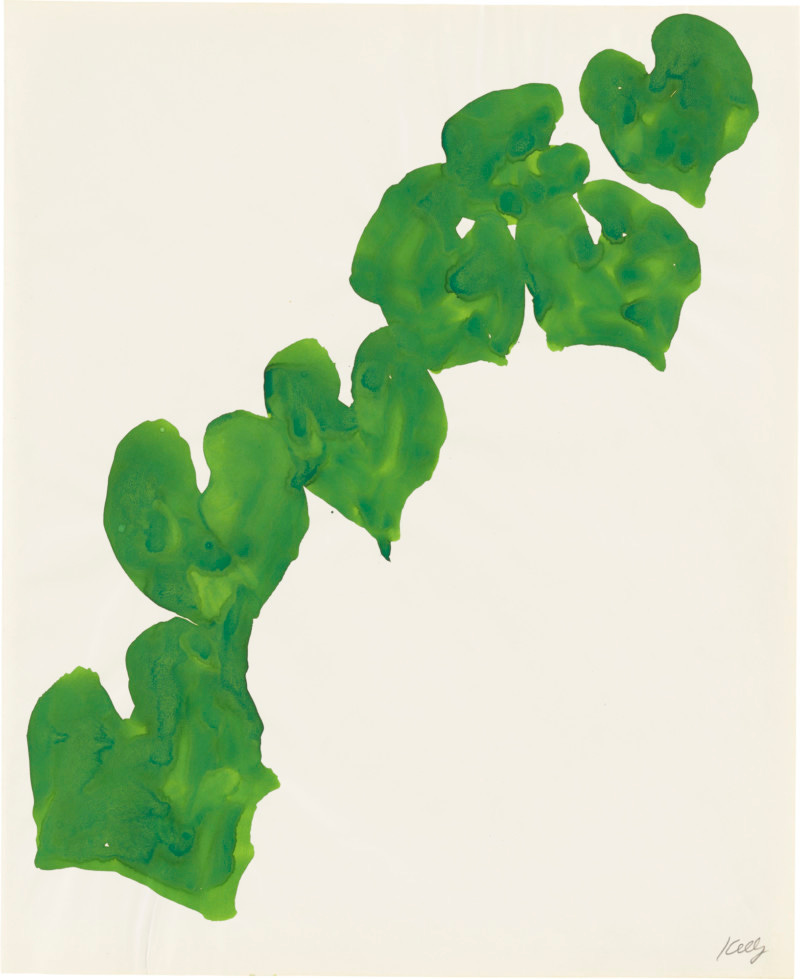

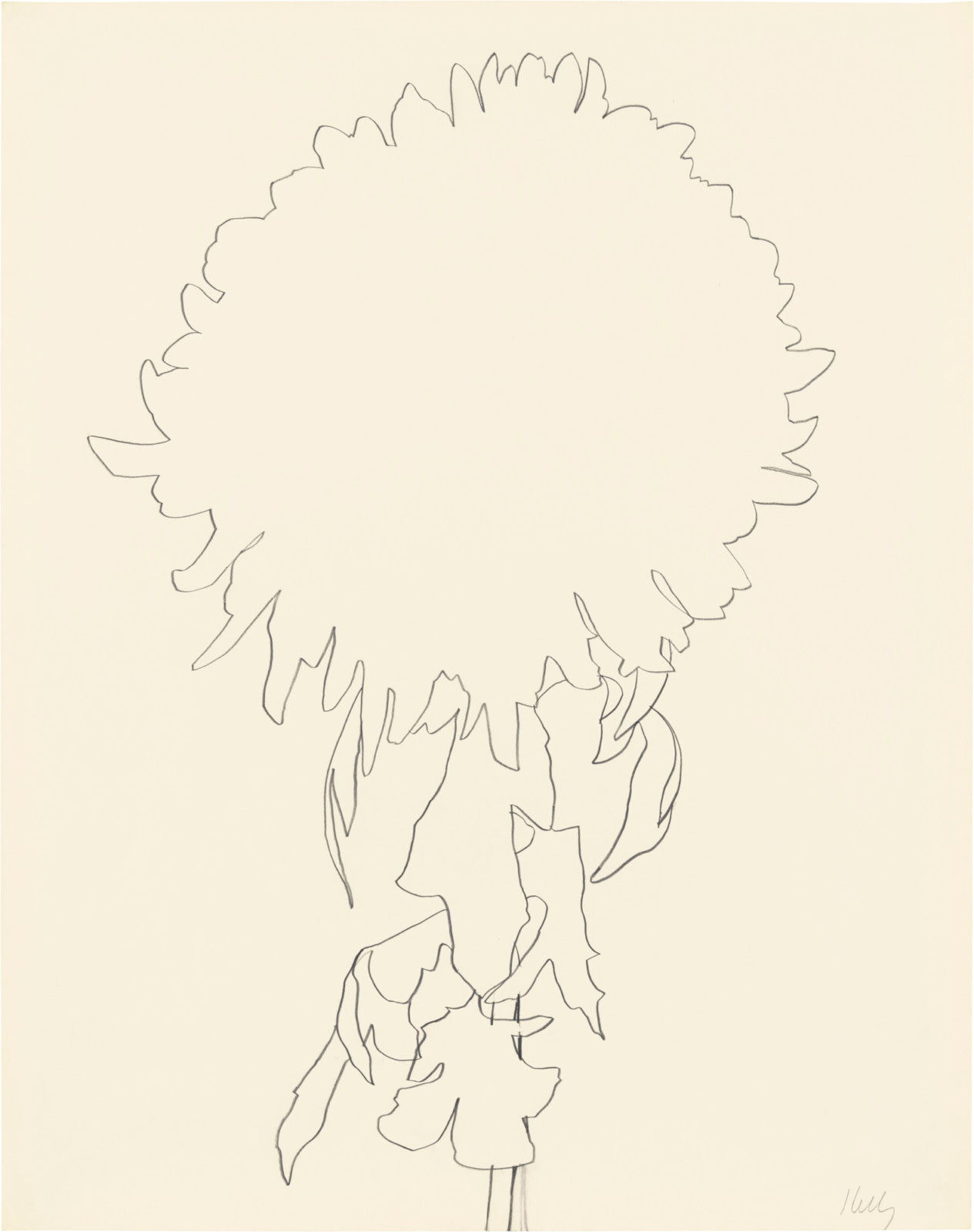

Ellsworth turned away from “the human figure and the set-piece of previous art” that he learned about in school, rejected “the dream world of Surrealism,” he saw in Europe, and instead turned to nature.4

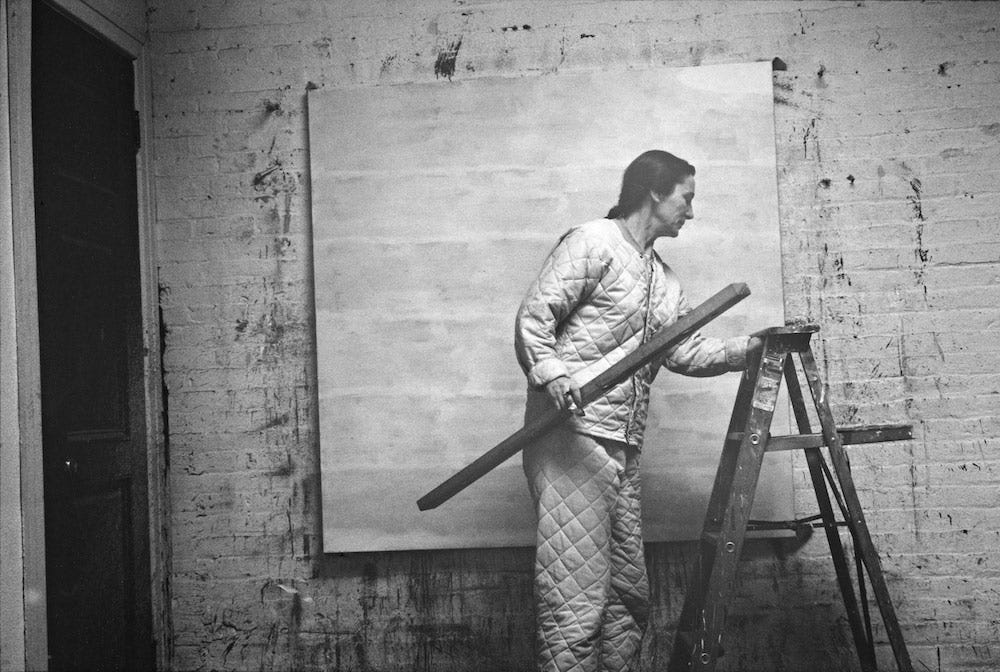

In the process, he sought “to eliminate the hand of the artist, to make the brushstroke invisible.” And yet, as Thomas Calvocoressi writes, “the effect is not clinical or robotic, but the reverse.” Because he didn’t want to “invent” pictures, and aspired to “get away from the cult of the personality,” Ellsworth Kelly said, “my sources were in nature, which to me includes everything seen.” Terry Winters, one of many young art students who was influenced by Ellsworth, explained that unlike other artists, he “rooted his abstraction in the real world.”

After seven years in France, Ellsworth Kelly returned to the United States at the age of thirty-one. When he arrived in New York, Robert Rauschenberg was making combines and Jackson Pollock drip paintings, and Kelly felt his art didn’t fit in. Upon the artist’s death, Peter Schjeldahl asserted that while in Paris: “Kelly missed out on the glory years of Abstract Expressionism in New York. How lucky was that, for him and us?” In group shows, his pieces often stood out as radical and unique. Ellsworth Kelly never backed away from his artistic vision, one that he would stick to for the next 50 years. The result is a truly original and lasting body of work.

“His paintings weren’t a kind of art. They seemed to present themselves as art in essence, immaculately conceived.” - Peter Schjeldahl

By 1960, Ellsworth Kelly had become an established New York artist, showing regularly and receiving growing public attention.5 But it would take decades before he gained the profile enjoyed by some of his contemporaries.

Today, his paintings sell for millions of dollars, with one piece—Red Curve VII—setting a Christie's auction record with its $9.8 million sale. His widower, photographer Jack Shear, has aggressively donated many of his husband’s works and their resulting fortune as outright gifts to museums across the country and grants in the arts. To date, Jack Shear has given away more than $30 million dollars and hundreds of paintings, remarking that spreading the wealth is fun. (As Mr. Shear put it, “Why not?”)

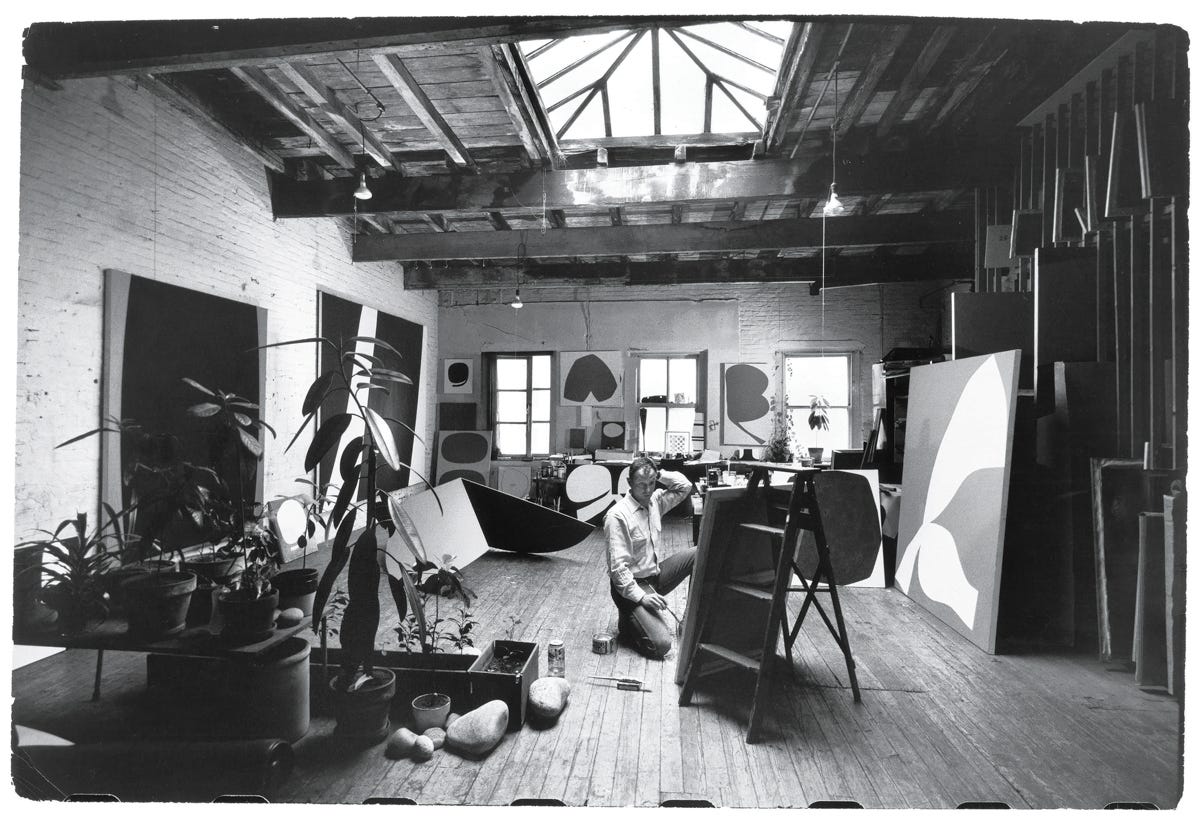

In 1970, after living in New York and Paris for three decades, Ellsworth Kelly decided to move permanently to a secluded hamlet in upstate New York not far from where he was born. He built a large studio and created a parklike garden to display his outdoor sculptures. In the final years of his life he suffered from emphysema—a result of longtime exposure to turpentine fumes—but still wandered the gardens and drew constantly, “sometimes making tiny sketches on a scrap of paper.” He referred to the oxygen tank that trailed him everywhere he went as his “tail.”6

Ellsworth lived with Jack Shear upstate for 32 years, in a house next to the studio where he worked. After the artist’s death in 2015, Jack preserved the studio intact as Ellsworth left it his last day working, and regularly photographed the space until the artist’s last canvases were removed. The New York Times shared some of those images in a 2017 article.

When the very last paintings the great artist ever made left the studio and went on view at the Matthew Marks Gallery, they were paired with a companion show next door, “Ellsworth Kelly: Plant Drawings.” Twenty five of his images of flowers, fruit, vegetables and leaves dating from 1949 to 2008, most never before exhibited, were designated a key part of the nature boy’s final legacy.

“There was so much to see, and it all looked fantastic to me.”

Ellsworth also had a dog: “Orange”

In addition to his love of birds and plants, Ellsworth also adored a dog named Orange. (Spectacular name, huh?)

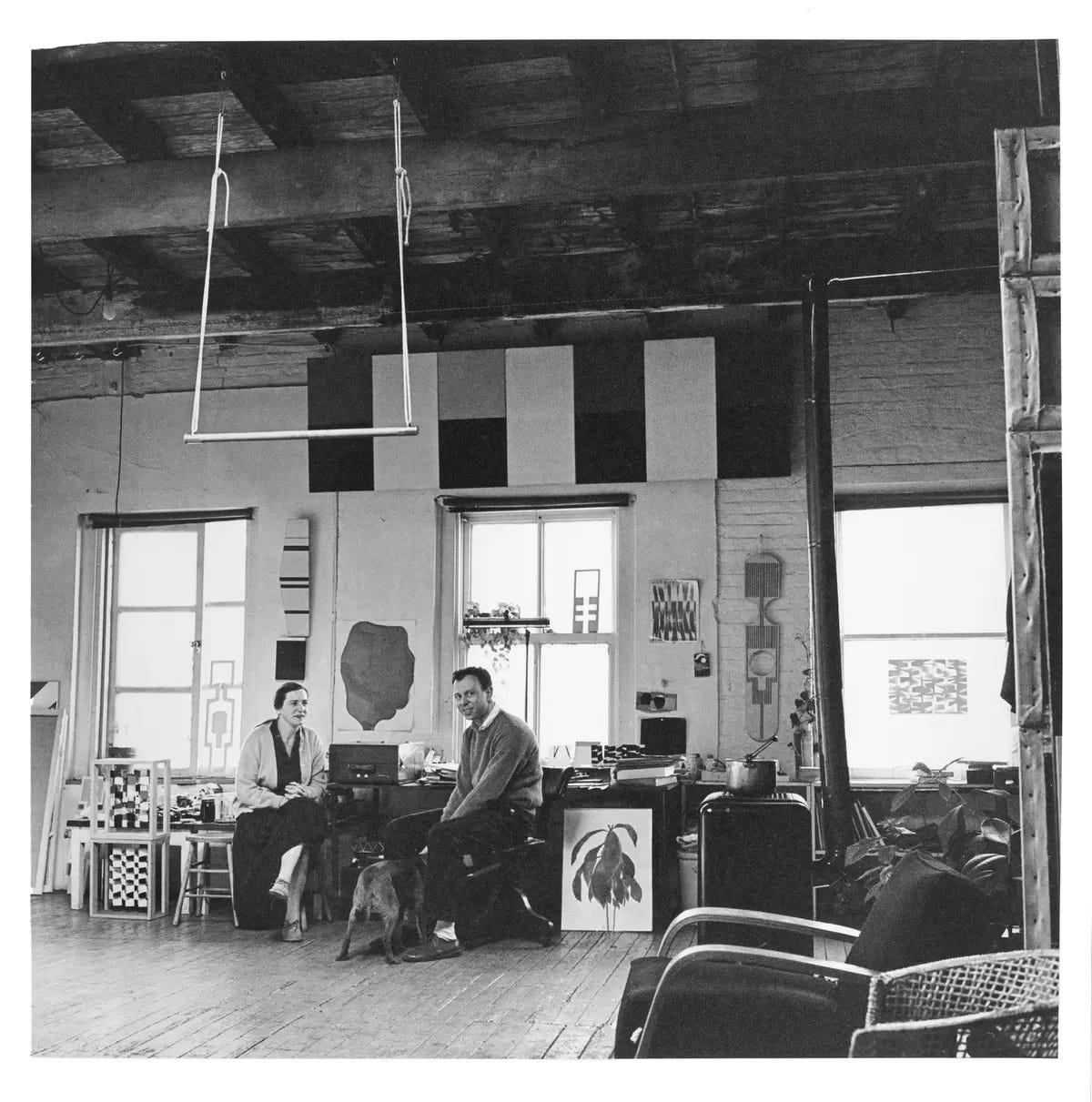

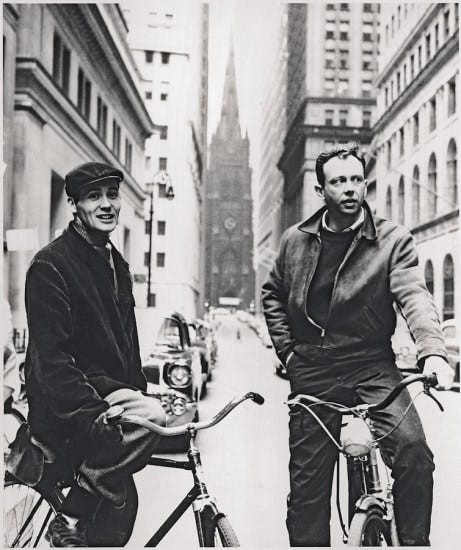

Orange accompanied Ellsworth through some of the most critical years of his career. The artist adopted him from two friends, the painter Jack Youngerman and French icon Delphine Seyrig, when he returned to the United States.

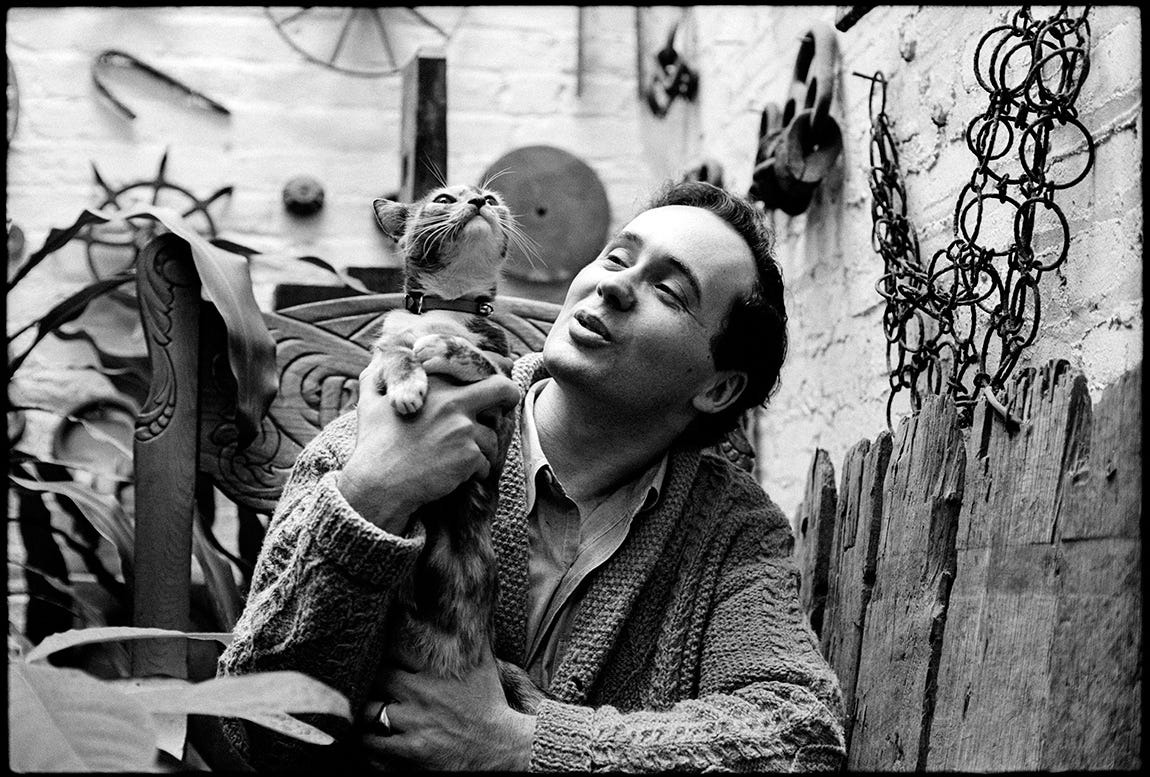

From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, Ellsworth lived with Orange close to Youngerman and Seyrig in a three-block radius of lower Manhattan called Coenties Slip. Other artists, including James Rosenquist, Robert Indiana (Ellsworth’s lover for a period of time), and Agnes Martin, lived in close proximity to Ellsworth in squat buildings. These artists all converged upon Coenties Slip in search of low rent (around $45 a month), ample floorspace in the abandoned maritime factories, and silence. The Slip was deserted at night, offering them an “exquisite” quiet in which they could focus on their work. Orange could often be be found milling around Ellsworth’s studio, sitting in the artist’s lap at his workbench, or lounging with the gang among the “sycamore and gingko trees of nearby Jeanette Park.”7

The photos of these now-iconic artists mingling at Coenties Slip are spectacular, and you can see Orange in a few of them. I’ve included some of these images below. I hope you enjoy them as much as I did.

Until next time, Art Dogs.

Here’s The New Yorker on the artist community at Coenties Slip:

There were times when life on the Slip must have felt like the kind of cornball bio-pic in which someone famous pops up every thirty seconds. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were minutes away. Frank O’Hara would drop by. In 1964, Andy Warhol shot a film in one of the buildings. In spite of attention from glossies such as Esquire, the area was never overrun by hangers-on—there was always a community but never really a scene. It helped, probably, that many of the buildings lacked reliable lighting, plumbing, or heating. (Harder to hang on when it’s freezing inside.) Artists loved the enormous rooms as much as the cheap rents, but by the late sixties most of the buildings had been demolished for high-rises—a bang in lieu of the usual gentrified whimper. Go there today and your reward is a grassless park, and an Insomnia Cookies around the corner.

…

Coenties Slip had seedy glamour to spare, but for most of the fifties and sixties it didn’t feel like Manhattan. The buildings were stubby and decrepit, and in some of them feral cats outnumbered humans; one real-estate developer complained that the area turned into a ghost town after 5 p.m. Because its lofts were commercially zoned, anyone who slept there at night was breaking the law, though landlords were happy to look the other way. If a building inspector came knocking, Seyrig and Youngerman could grab a set of slatted doors that they had found on the street, hide their bed behind them, and pretend to be decent, law-abiding business owners.

…

[The Slip artists] lived below Fourteenth Street, but they were never pillars of the downtown art scene. Tenth Street, where Pollock and the leading Abstract Expressionist painters of the era drank and gabbed, might as well have been Canada. “One of the things we were very conscious of,” Youngerman later said, “was the fact that we all knew that we weren’t part of the de Kooning/Pollock legacy in art.” He was talking about something both broader and narrower than Abstract Expressionism: art as gruff male ego, epitomized by the famous Hans Namuth photographs of Pollock bobbing like a middleweight and hurling paint like a pitcher. Slip artists, many of them gay, and many of them women, were proud to scorn this model.

![Untitled, 6/22/04, 9:32 AM, 8C, 3806x4376 (667+1596), 88%, John, 1/120 s, R74.2, G61.0, B72.7 [Agnes Martin (at right) on rooftop of the Coenties Slip building, Jack Youngerman (sitting), Ellsworth Kelly (standing), Robert Indiana (kneeling), Delphine Seyrig, 1957] Untitled, 6/22/04, 9:32 AM, 8C, 3806x4376 (667+1596), 88%, John, 1/120 s, R74.2, G61.0, B72.7 [Agnes Martin (at right) on rooftop of the Coenties Slip building, Jack Youngerman (sitting), Ellsworth Kelly (standing), Robert Indiana (kneeling), Delphine Seyrig, 1957]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xO_7!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6cfee0da-aaaa-4a3e-a88a-5621c6d38f6f_820x1060.jpeg)

https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2535_300299040.pdf

https://www.apollo-magazine.com/ellsworth-kelly-centenary-postwar-abstraction/

https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2535_300299040.pdf

https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2535_300299040.pdf

https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2535_300299040.pdf

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/03/arts/design/ellsworth-kelly-last-paintings.html

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/columns/formerly-deserted-waterfront-neighborhood-attracted-cast-young-artists-lower-manhattan-mid-20th-century-1234675400/

This made me nostalgic for a time I’ve never known. Love Ellsworth Kelly’s work and delightful to discover his affinity for birds 🐦 and Orange the dog 🐶 🍊

Wonderful post!

Last year this website was produced as part of the centennial celebration of his birth. https://www.ek100.org/