Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

I am 36 years old.

One of my favorite artists, Félix González-Torres, died at 38 years old of AIDs, almost thirty years ago now.

And five years before his own death, Félix González-Torres lost his partner, his “one great love,” Ross Laycock to the same disease.

This post is about their love story.

Born in Guáimaro, Cuba, in 1957, art came to Félix González-Torres early. In the second line in his autobiography, he notes the day when “Dad bought me a set of watercolors and gave me my first cat.” (From that day forward, cats were also a “constant part of his life,” according to Natalia Grabowska, Assistant Curator at The Serpentine Galleries.)

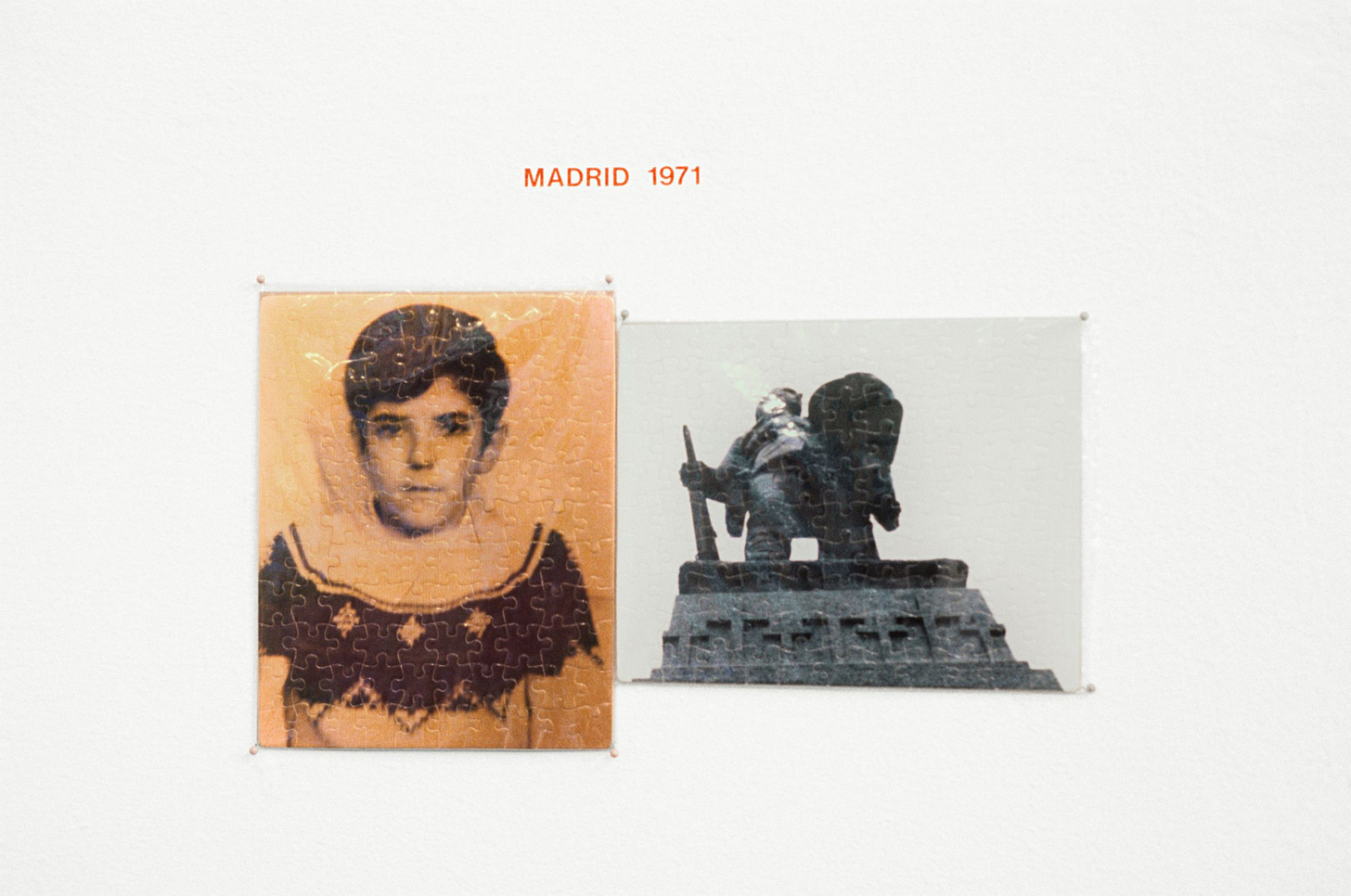

At 14 years old, Félix’s parents sent him and his sister to Madrid to flee the Cuban revolution. No family or friends were waiting for them in Spain, and they were taken in by nuns. Soon the two siblings moved to Puerto Rico to stay with an uncle. It would take another decade for their family to reunite in full.

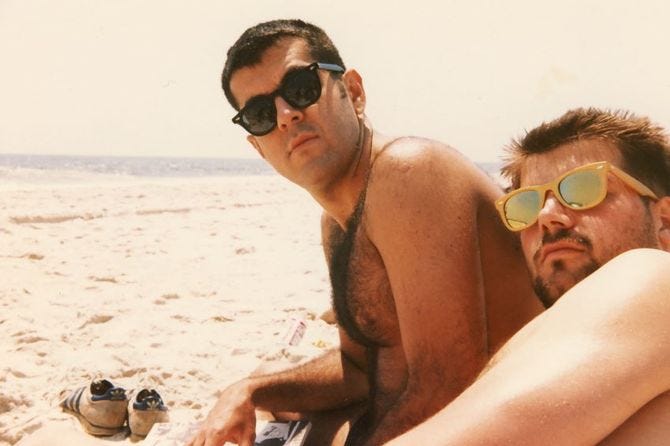

In 1979, Félix moved to New York after earning a scholarship to further his studies at Pratt. He met Ross Laycock four years later at Boy Bar, a gay bar on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. Ross was a sommelier. He was close to finishing his Bachelors in Biochemistry with a minor in English Literature when he died in 1991. He was also a cat and dog-lover. “He did everything; he was a Renaissance man,” Félix later said about Ross in an interview. “And gorgeous too, really gorgeous. Fucking hot! But intimidating, the first time around.”

Félix and Ross were together for eight years. In that time, their lives became “intertwined like the strands of a helix.”1

Ross was diagnosed with HIV five years into their relationship, in 1988. He didn’t realize he had the virus until he had his appendix removed and the medical staff tested his blood. It was HIV positive.

Félix’s response to Ross’s diagnosis was to document, write letters, and make art. In When This You See Remember Me, former MoMA curator Robert Storr argues that “the constant reminder of sickness and impending death for Gonzalez-Torres made his art production at times a necessary and urgent calling.”

And so just as Ross was facing death, Félix’s star began its incredible rise in the art world.

Ross’s life informed many of the artist’s greatest pieces. Up until his own death, Félix repeatedly proclaimed that his art was made for an audience of one: Ross. His tremendous output during this period led to an exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York in 1995, when Félix was just 37 years old. The exhibition should have been a mid-career survey, but proved to be a retrospective.

Let’s take a look at a few of the pieces Félix made for Ross.

Untitled (Perfect Lovers), 1987-1990

In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was no effective medical intervention once HIV transformed into AIDS, leaving patients with a 12 to 18 month life expectancy. So when Ross received his diagnosis, a countdown began.

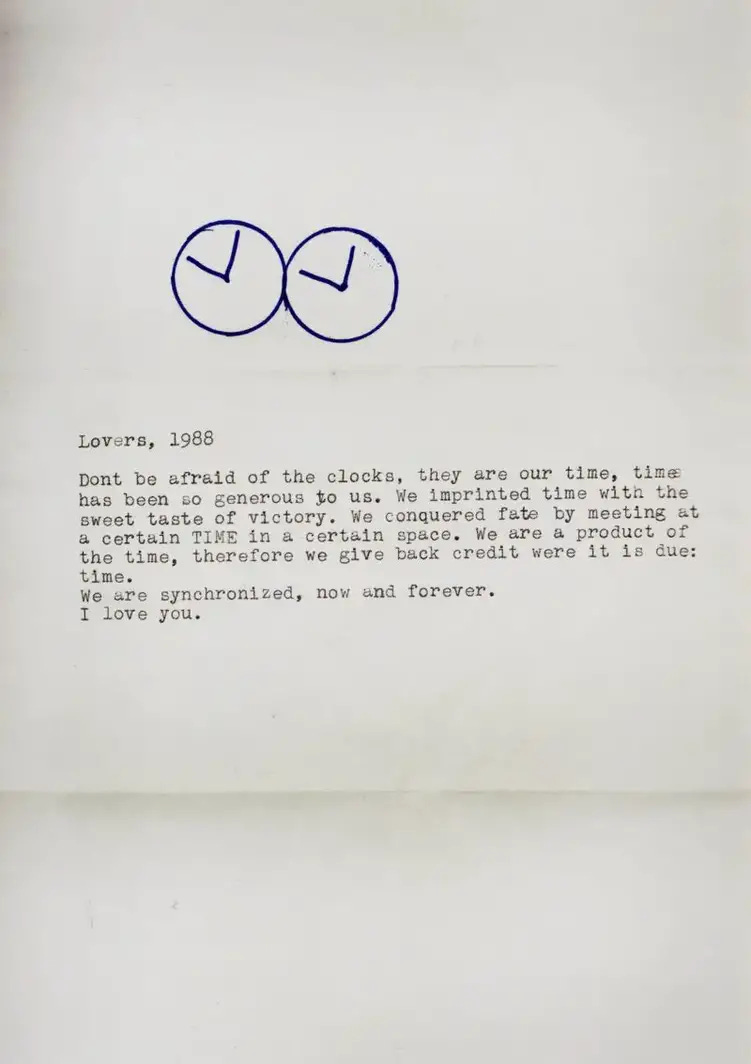

In a letter to Ross in 1988, just after his diagnosis, Félix first showed him a rough sketch of a piece entitled “Lovers.” It consists of two clocks touching each other that start in synchronization. The two clocks represent the two men’s mechanical heartbeats.

In the letter, Félix ruminates about time in what amounts to one of the most beautiful love letters I have ever read:

Don't be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, the time has been so generous to us. We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. We conquered fate by meeting at a certain time in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit where it is due: time. We are synchronized, now forever. I love you.

When Felix developed the idea for Untitled (Perfect Lovers), the two lovers’ hearts were still beating. Slowly, the clocks would fall out of time, caused by both the running out of batteries and the very nature of the mechanics.

Félix reflected that before making this piece, time had scared him—that making the artwork was “the scariest thing I have ever done.” He told Bomb Magazine: “I wanted to face it. I wanted those two clocks right in front of me, ticking,” and later said “I thought of that phrase from Freud: we prepare ourselves for our greatest fears in order to weaken them.”

Félix specified that future displays of these clocks should include a distinct blue color, which is often incorporated as the wall paint (see above). The blue he used was the color of Ross's hospital gown at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Toronto. You’ll notice the same shade of blue in later pieces, and even spot it in the invite to Félix’s own memorial.

“Love gives you a reason to live, but it also brings panic: the fear of losing that love.” — Félix González-Torres

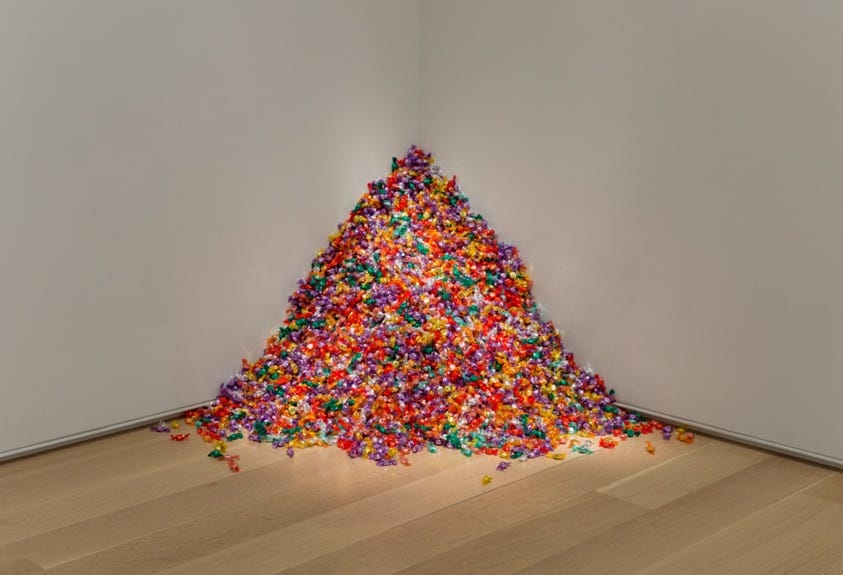

“Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991

Ross lived with HIV for three years before passing. When the couple first met, he was 195 pounds. “He was a fucking horse,” Félix said. “He could build you a house if you asked him to.” Soon, his weight dropped to 175 pounds, slimmer but still healthy.

Félix recalled watching Ross vanish in an interview.

FGT I know you’ve seen it the same way I’ve seen it, this beautiful, incredible body, this entity of perfection just physically, thoroughly disappear right in front of your eyes.

RB Do you mean disappear or dissipate?

FGT Just disappear like a dried flower. The wonderful thing about life and love, is that sometimes the way things turn out is so unexpected. I would say that when he was becoming less of a person I was loving him more. Every lesion he got I loved him more. Until the last second. I told him, “I want to be there until your last breath,” and I was there to his last breath. One time he asked me for the pills to commit suicide. I couldn’t give him the pills. I just said, “Honey, you have fought hard enough, you can go now. You can leave. Die.” We were at home. We had a house in Toronto that we called Pee-Wee Herman’s Playhouse Part 2 because it was so full with eclectic, campy, kitsch taste. His idols were not only George Nelson and Joseph D’Urso, but also Liberace.

In the month’s after Ross’s death, Félix made Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991. He invites viewers to take candy from the pile home with them—to consume the sculpture, which Félix specifies should ideally weigh 175 lb., Ross’s healthy body weight.

This piece, like most of Félix’s work, requires an audience. “I need the viewer,” he told Tim Rollins in a 1993 interview. “Without the public, these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work … to help me out, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in.”

Félix wanted this piece and others he made to spread and to exist in multiple places at the same time through participation by the viewer. MoMA writes the “pieces just disperse themselves like a virus that goes to many different places—homes, studios, shops, bathrooms, whatever,” much like HIV.2 But the virus that Félix’s work spreads isn’t life threatening; it’s life extending. As Jennifer Tucker described it, “By taking a piece, you are taking Ross with you, thus making him omnipresent.”3

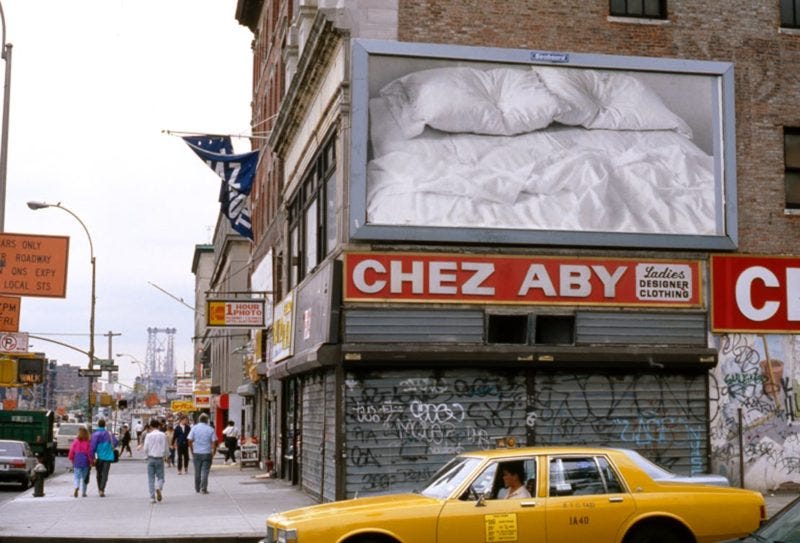

“Untitled.” 1991

Ross died on January 24, 1991. One month later, Félix first mounted Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) on a billboard in Manhattan.

The photograph is a simple, black-and-white image of unmade sheets and pillows. Note the depression in the center of each pillow, suggesting a recent presence now absent. The intimate, silent image was jarring to see on billboards in the middle of Manhattan, where they were first exhibited. The image feels even more poignant with the knowledge that it’s a photograph of Félix Gonzalez-Torres’ own bed.

He pasted these visual elegies on 24 billboards in total over the course of a few weeks—24 to honor the day Ross passed away. They have since been installed around the world, from Texas to Korea.

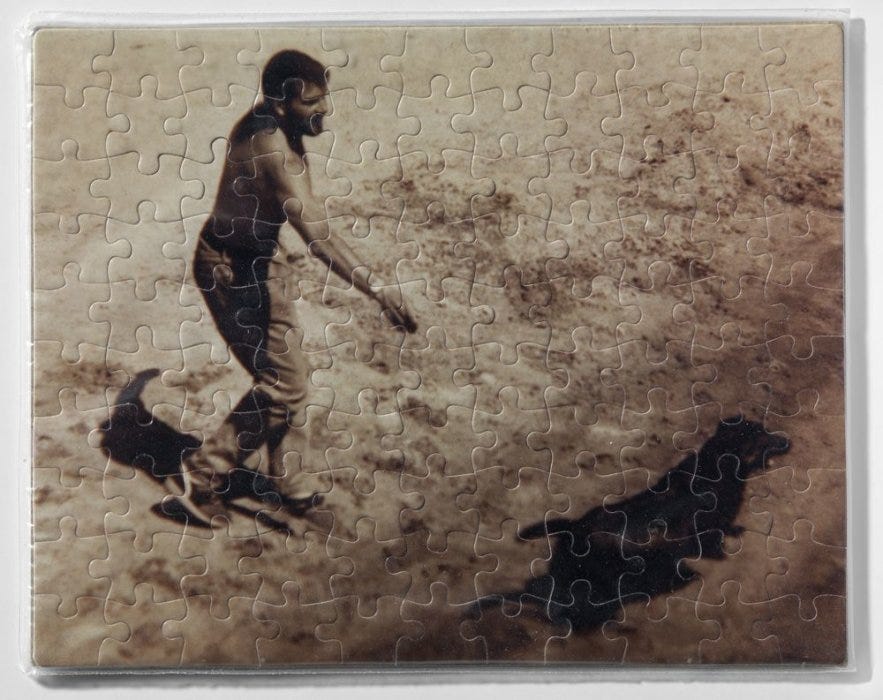

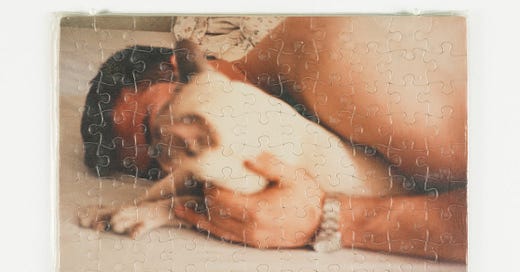

Puzzles, 1987-1992

Félix created photographic puzzles from 1987 until 1992, his longest engagement with any one body of work.

The puzzles realize two of his core themes: the use of readily available materials, and creating pieces that are at once fragments and whole, presence and absence. He made 55 puzzle works, including a few of Ross with his dog, Harry, and their pet cats. They come disassembled in a plastic bag. It’s up to the viewer to put Félix’s and Ross’s memories back together—to resurrect them.

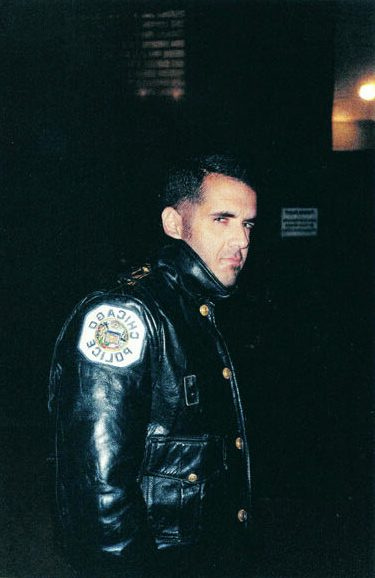

One strange thing you’d notice if you research Ross and Félix is that there’s an extremely limited number of photos of each of them available online.

And of the photos one can find of Ross and Félix, quite a few include a dog or a cat.

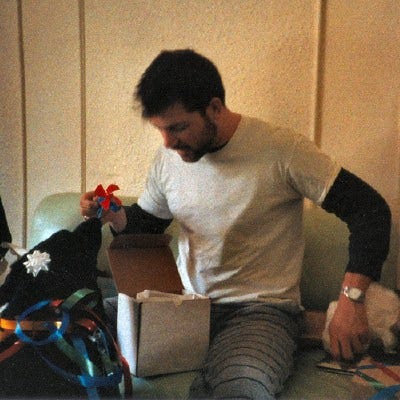

We’ve seen some of the remaining photos of Ross already, above, with cats and his dog Harry. A few of the other photos you can find of Félix are likely all from the same day in 1993 at his own apartment. If so, these photos would have been taken two years after Ross’ death, and three years before his own.

After Ross’s death, Bruno and Mary, two black cats that Ross had found in his hometown of Toronto, moved in with Felix. In an attempt to rebuild his life, he “moved the four cats, books, and a few things to a new apartment.”4

In these photos I found from 1993, he appears to still be acting as a caregiver—no longer for Ross but for Ross’s cats and for a new dog named Oscar. (My suspicion is he named his bulldog after Oscar Wilde, whom he referenced in an artwork.)

The significance of these cats and dogs reveals itself in the snapshots Félix took from 1991 to 1995, which were later published in a beautiful book. Félix had a practice of taking personal photographs and mailing them to his friends and family with short messages on the back. Similar to his other works which the public are invited to take, the photographs were also made to be owned by many, distributed through Félix’s personal network. Ross’s cats, and Félix’s bed, are a consistent theme in the snapshots.

In this period after Ross’s death, when he was cranking out masterpieces, it’s as though Félix’s life was a kind of purgatory. One year before his own death, Félix said in an interview:

FGT I never stopped loving Ross. Just because he’s dead doesn’t mean I stopped loving him.

RB Well, life moves on, doesn’t it, Félix?

FGT Whatever that means.

RB It means that you get up today and you try to deal with the things that are on your mind.

FGT That’s not life, that’s routine.

RB No, it’s not.

FGT Oh, yes, it is.

Félix’s life had not “moved on.” It never would. Carl George, one of Ross and Félix’s closest friends believes that Félix, “couldn’t help but cling to the past because a big part of him died with Ross.” Félix’s existence became a series of artistic and domestic rhythms—a routine that supported making art but not an expansive, vibrant life.

Carl George felt there was no way to compare Félix’s life with and without Ross. “He was a different person.” The tragedy was simply too great to overcome.

Félix was a great romantic. Ross was Félix’s one great love… Félix struggled deeply until the day he died because he and Ross were robbed, murdered while young. They could have gone the distance. The anger we all felt is impossible to imagine. But you don’t see that in the work he created between 1991 and 1996. It is resolute, profound and elegant, as always.5

It’s safe to assume that, though Félix Gonzalez-Torres’ art from this period translates to timeless universal themes, creating these pieces also served a deeply personal need for him. He had to find some way to process and cope not only with the deterioration of the love of his life, but also the onset of his own illness, and eventual death.

While he was in this purgatory period, heartbroken and angry all at once, we can at least hope that having his and Ross’ cats at home, and his bulldog, Oscar, offered the artist some amount of stability and solace. Perhaps they helped him have the strength to make such transcendent, timeless art.

Beads in the color of Ross’ hospital gown. These bead works suggest the possibility of a portal into another dimension or afterlife. Viewers are required to pass through these beads in order to reach the other side.

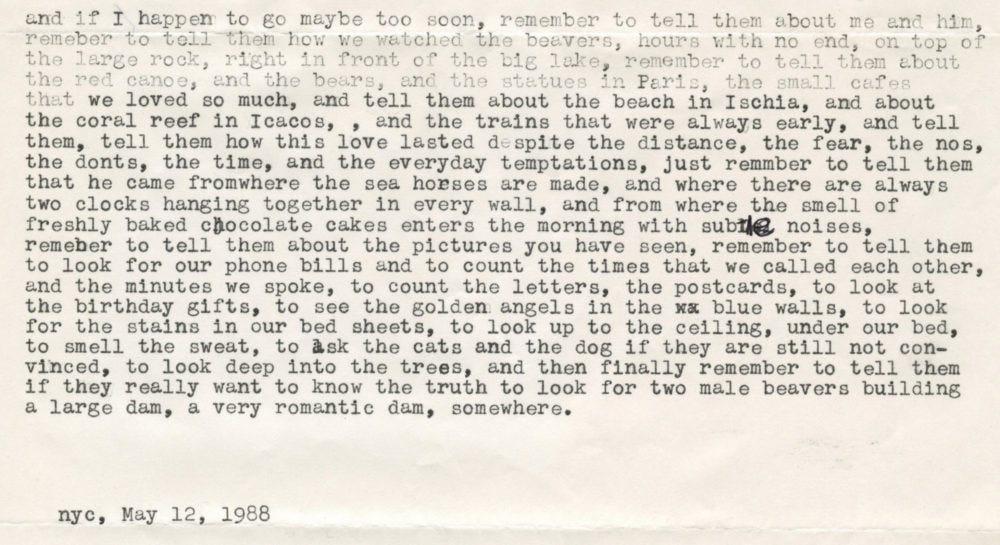

Back in 1988, when Félix was first processing Ross’s diagnosis, he wrote a letter to Carl George, the couple’s closest friend. “If I happen to go maybe too soon, remember to tell them about me and him” he began.

Carl fulfilled Félix’s request to tell all of us about Félix and Ross’s romance. He collected the lovers’ memories and created a digital archive. “The pictures” and “the letters, the postcards” and the other testaments to the couple’s love I found in my research for this post came from Carl’s efforts.

And Félix did his part as well. So many of the memories he cites in this 1988 letter to Carl—the big lake… the red canoe…the beach in ischia…the two clocks hanging together in every wall…the blue walls…the stains in our bed sheets—he spent the next eight years turning into artworks.

Upon looking back, it almost seems as though Félix had a masterplan. His frantic output during those years of loss and purgatory was a grand gesture to preserve the memory of his love story. As a result, Félix and Ross will live on through these artworks—artworks that we’ve touched with our hands, put in our mouths, and hung up on our walls, streets, and greatest museums.

Laura Bravo once wrote: “through the process of losing his life, Félix González-Torres [gained] immortality.”6 But it’s not just Félix who became immortal. It’s the artist and his subject, his most important audience: Ross.

Those loverboys will last forever.

Rest in peace, Ross and Félix.

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Joe Clark-torres-y-las-vanitas-barrocas-por-laura-bravo-lopez/

https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/04/04/printout-felix-gonzalez-torres/

https://www.thelondonlist.com/culture/felix-gonzalez-torres

Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled Biographical Sketch.”

https://visualaids.org/blog/carl-george-fgt-ross-laycock

Laura Bravo, ‘Félix González Torres: The Fleeting Life of Flesh and Objects’ (https://www.academia.edu/6030843/Félix_González_Torres_The_Fleeting_Life_of_Flesh_and_Objects) Accessed 1 July 2020.

I loved reading this.

This touches my heart so deeply. And I am moved by how such a uniquely personal experience translated into art taps into the very universal experiences we all have with love and loss and illness and grief and fear. And also how the work can live today as a means to create understanding and empathy around such a unique time in our history when those qualities of empathy were often so very lacking.