Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

George Balanchine was born Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1904. By the age of 17, he was a dancer at the State Theater of Opera and Ballet (formerly the Mariinksy Theater) where he choreographed, danced, and organized an experimental ballet company.

In his early 20s, during a tour in Germany, his troupe decided to defect from the Soviet Union. They met with remarkable hardship along the way:

All performances in Berlin were met coldly. The Young Ballet had to perform in small cities of the Rhine Province such as Wiesbaden, Bad Ems, and Moselle. [Georgi’s first wife Tamara Geva] wrote later, that in that time they had to dance “in small dark places, in summer theaters and private ballrooms, in beer gardens and before mental patients.” They could barely afford paying for hotels and often had only tea for meals. In London, they had two weeks of very unsuccessful performances, when the audience met them with dead silence. With expiring visas, they were not welcome in any other European country. They moved to Paris, where there was a large Russian community.1

Despite all of this adversity, Balanchine’s talent still shone through. Sergei Diaghilev invited 21-year-old Balanchine to join the Ballets Russes as a choreographer. (Diaghilev also insisted that he change his name from Balanchivadze to Balanchine.) The Ballets Russes is widely regarded as the most influential ballet company of the 20th century. Balanchine worked across Europe, and collaborated with some of the best artistic minds of the era: composers such as Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, and Maurice Ravel, and artists who designed sets and costumes, such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, and Henri Matisse.

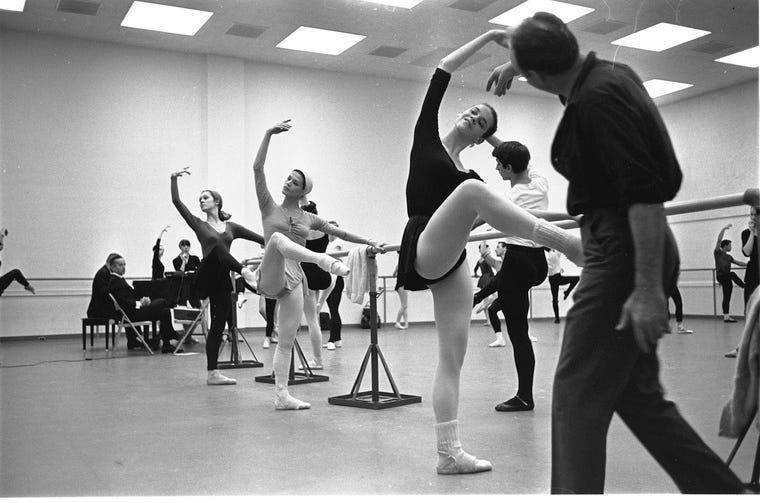

In 1933, Balanchine was invited to the United States, where he established the first truly American ballet company—the School of American Ballet. (The School of American Ballet became and remains a home for dancers of New York City Ballet as well as companies from all over the world.) Compared to his classical training, Balanchine thought Americans could not dance well. He wanted to develop dancers who had strong technique.

It was in the United States that Mourka the cat came into Balanchine’s life.

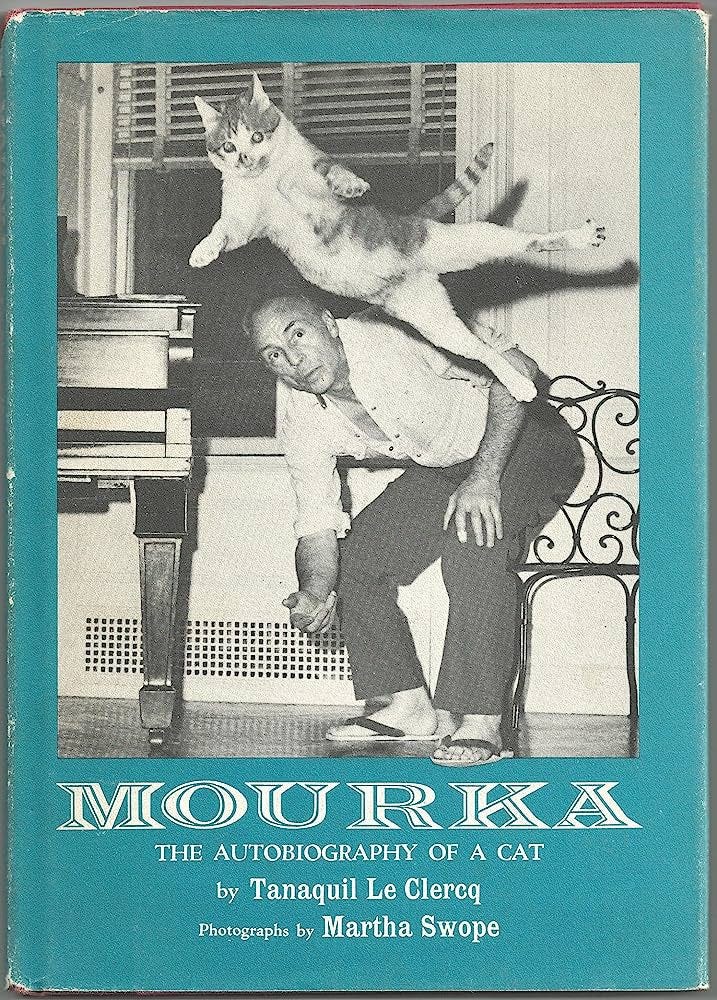

Mourka was an “alley cat,” who was rescued by Tamara Karsavina, a famous ballet dancer. Balanchine and his fifth (and last) wife, Tanaquil Le Clercq2, named the young cat Mourka—the most common female cat name in Russia—before realizing he was a boy. The name stuck. Described as “a white-and-ginger-colored cat,” Mourka was “a pampered and much admired creature.”

Mourka became yet another pupil for Balanchine.

The great choreographer put in considerable time “training” Mourka, and would have his cat perform for friends. According to Balanchine: A Biography by Bernard Taper:

Balanchine had trained this cat to perform brilliant jetés and tours en l’air; he used to say that at last he had a body worth choreographing for. He talked of presenting Mourka publicly, in a program titled—in parody of the revolutionary program he had presented as a youth in Russia—“The Evolution of Ballet: From Petipa to Petipaw.” Once, at a party at his apartment during the Christmas season, [Igor] Stravinsky asked to see Mourka perform. Guests present later said that was the only time they had ever seen Balanchine nervous before a performance.

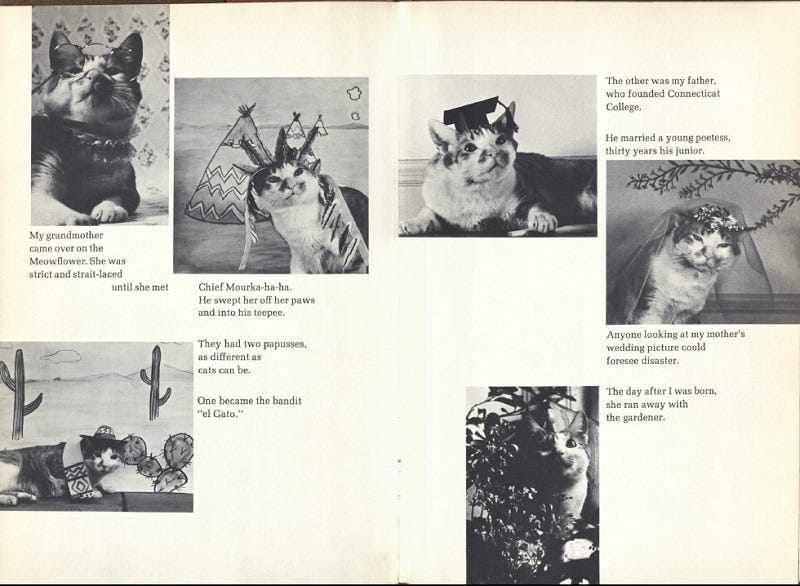

A photograph of Mourka performing with Balanchine (see below) was featured in Life magazine and was so well received that it led to a book deal. Famed ballet photographer Martha Swope’s pictures of Mourka were paired with facetious, comedic writing by Tanaquil Le Clercq, Balanchine’s wife who was spending most of her days at home with Mourka.

The playfulness of this book and the devotion Balanchine showed to training his cat at home take on a deeper meaning when you learn more about his and his wife Tanaquil Le Clercq’s life during this time.

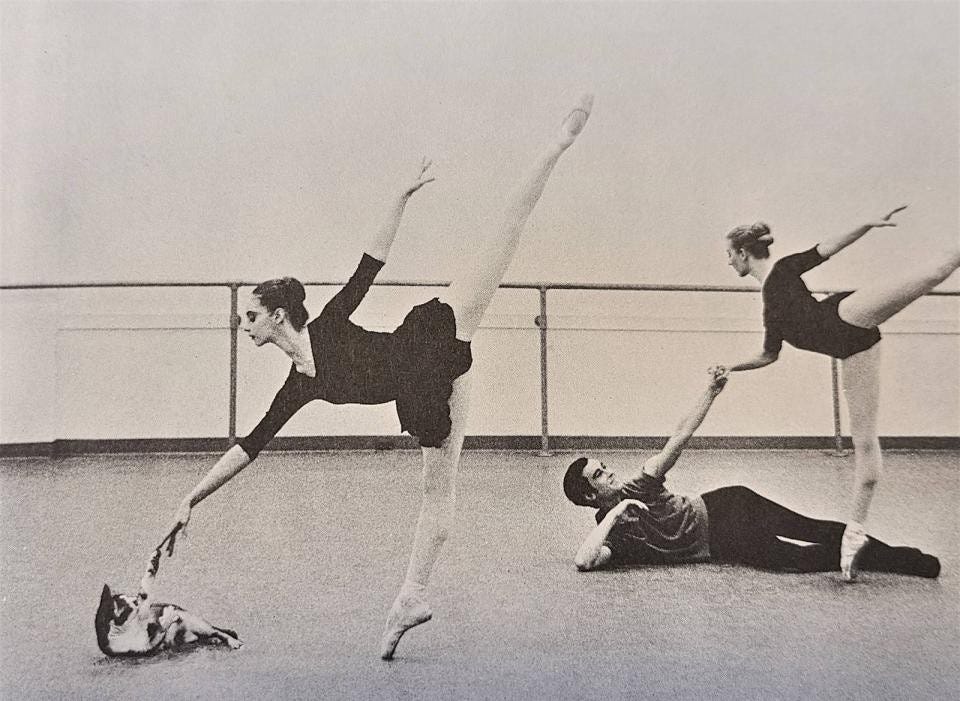

Le Clercq was a ballet prodigy. At 10, she was awarded a scholarship to Balanchine’s School of American Ballet. She became Balanchine’s star student at just 15 years old. In addition to Balanchine, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Frederick Ashton, and Antony Tudor also created ballets for her3. At 23, Le Clercq wed Balanchine. But at 27, in her prime, Le Clercq was stricken with polio during a European tour. Paralyzed from the waist down, she was confined to a wheelchair for the rest of her life. As her close friend Holly Brubach recalled:

Her presence onstage was breathtaking and heartbreaking. It’s impossible now to watch the handful of her performances that have survived on film without a sense of foreboding. She holds nothing back, devouring every role, with an incandescent charisma and an irresistible charm that conveys the sheer joy of being airborne or turning on point or swooning into her partner’s arms. Her range was astonishing.

When Le Clercq came down with polio, it made international news. Balanchine was devastated, and took a yearlong leave from his company to be with Le Clercq and search for treatments. According to Holly Brubach, Le Clercq, “always knew she would never walk again, but she made the effort for [Balanchine] because he couldn’t bear the thought.”4

The hero of this story, in my eyes, is Le Clercq. As Le Clercq later reflected, “I could have gone on, he couldn’t.” While Balanchine spent the year after her illness diligently teaching his cat to dance in lieu of being able to teach his students and wife, Le Clercq began to make something brand new and different of her creativity, starting with a playful, silly book about the alley cat in her home. She would go on to also publish The Ballet Cookbook, based on recipes she cooked for elaborate dinners her and Balanchine hosted for friends during this time. She also developed a passion for photography and crossword puzzles, and even published some of her own in the New York Times. Holly Brubach said of her friend’s spirit: “To hear [Le Clercq] tell it, she had just gone on. In fact, just going on required a choice.” But through my lens researching her life, I don’t see someone who was merely putting one foot in front of the other after tragedy. Le Clercq brought many new forms of delight, humor, friendship, and creativity into her life after she lost the use of her legs. In the midst of the darkest moment of one’s life, if that’s not heroic, I’m not sure what is.

After 17 years together, Balanchine and Le Clercq divorced in 1969. (Reportedly, he asked for a divorce so he could woo another dancer.) Le Clercq would return to dance as a teacher a few years later.

After years of being unwell, Balanchine died on April 30, 1983, at the age of 79. Le Clercq passed away 17 years later, from pneumonia, at the age of 71.

The trailer for a documentary film about Tanaquil Le Clercq that was released in 2013.

Thank you for reading Art Dogs. If you’d like to receive future editions in your inbox, subscribe here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Balanchine

She was named for the first Etruscan queen of Rome, and was called Tanny by her friends

https://miscelana.com/2022/04/13/the-moving-story-of-tanaquil-le-clercq/

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/t-magazine/inside-the-mind-of-tanaquil-le-clercq.html

The story of Le Clercq always gets to me, amazing woman. Wonderful post, I love that it was the only time Balanchine was nervous about a performance! 🐱

I'm so excited to see a cat featured on these pages 😺