Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

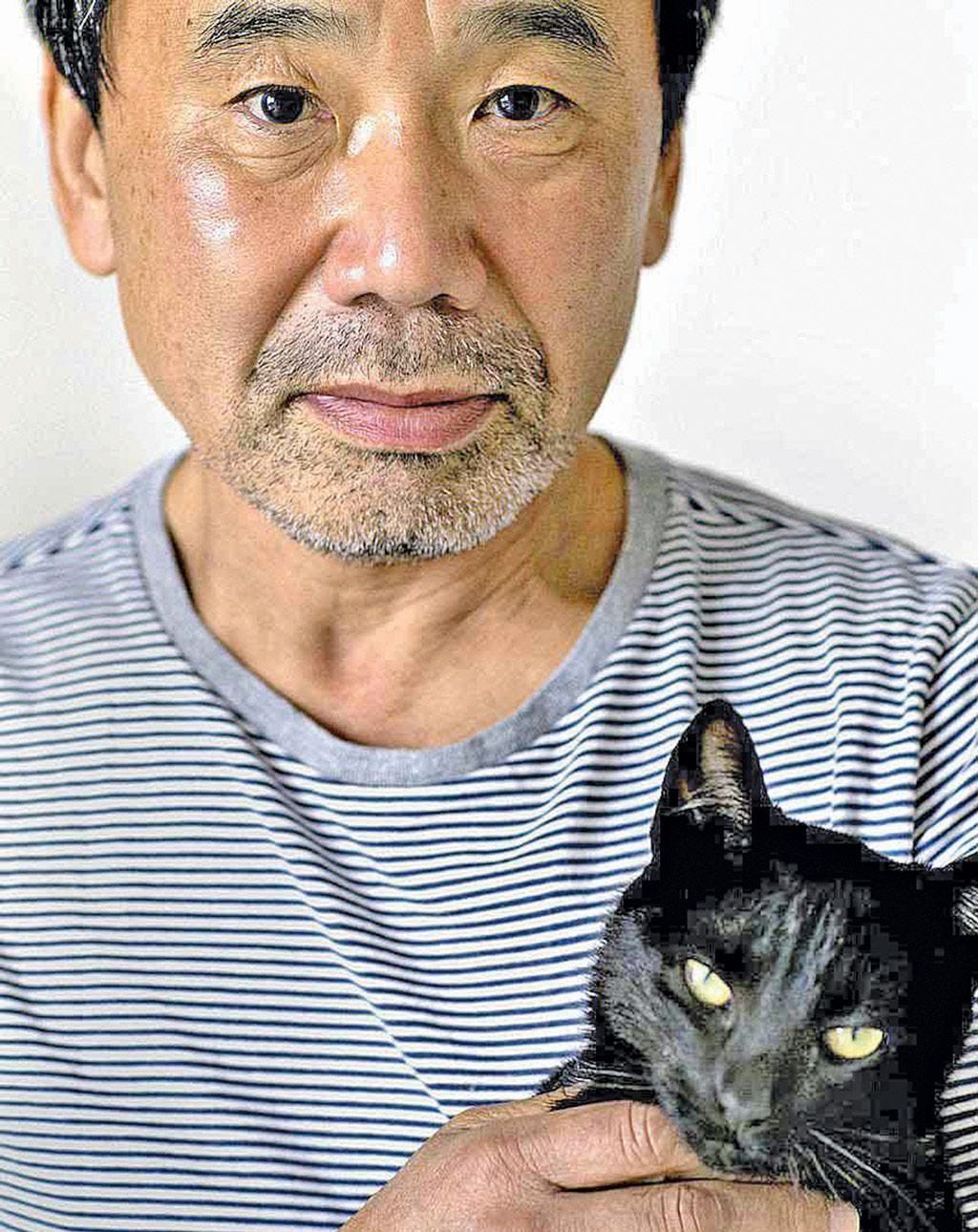

Haruki Murakami has written more than 30 novels and is the most widely-read Japanese novelist in the world. He has won virtually every prize Japan has to offer, including its greatest, the Yomiuri Literary Prize, and is a regular on the list of possible recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Haruki wrote his first book Hear the Wind Sing1 at 29 years old, and it won the coveted Gunzo Literature Prize. In 1987, he published Norwegian Wood, which has sold at least 10 million copies in Japan alone.2

He is also an active translator, and credited for bringing writers like Raymond Carver and F. Scott Fitzgerald to Japanese readers.

But before all of his fame and literary contributions, he was a bar owner who was obsessed with jazz and cats.

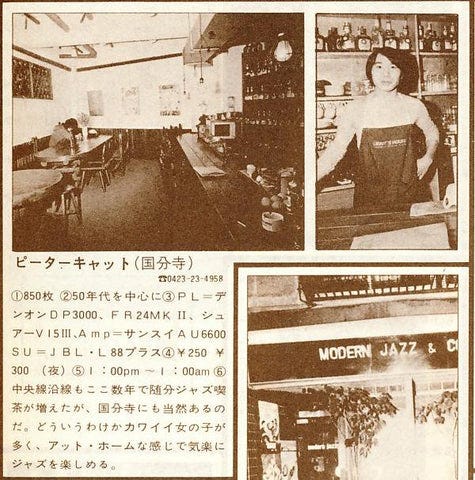

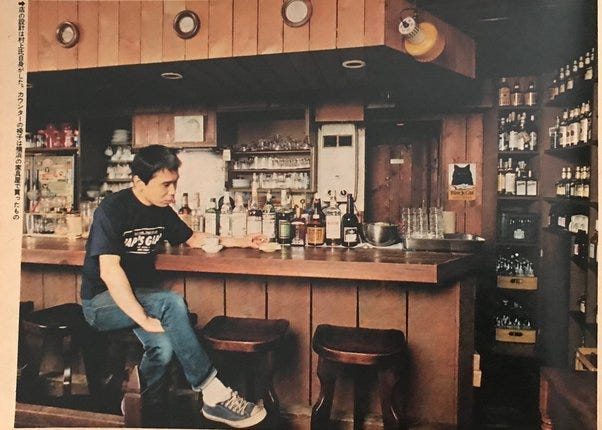

Haruki Murakami was just a 20-year-old university student when he met his wife, Yōko Takahashi. Coming of age in the late 1960s, the couple hated the idea of being a part of “the system” and doing salaryman-type office work after graduation. So in 1974, before they had even graduated, they decided to open a jazz bar in Kokubunji in the western outskirts of Tokyo. They named the bar Peter Cat, after their pet cat. The first location was in a basement. Aaron Gilbreath writes:

The club served coffee during the day, and drinks and food at night. On weekends, it hosted live jazz. In a smoky, windowless room, Murakami washed dishes, mixed drinks, swept, and booked musicians. When bands weren’t performing, he spun records from a collection of 3,000 (which has since grown to more than 10,000).

(Imagine that! Do you have 10,000 of anything?)

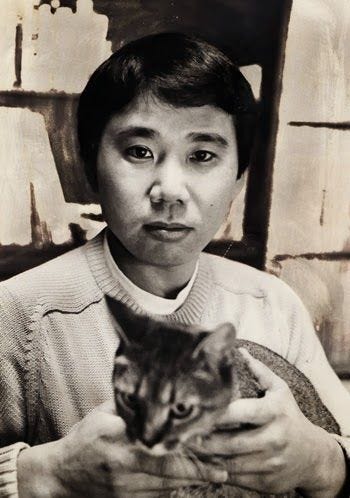

The young couple went so deep into debt that they reportedly couldn’t afford heating. Instead, during the cold winter nights, the author recalls that they “snuggled with their cat for warmth,” whose name was Peter—the bar’s namesake.

What motivated Murakami to endure so much hard work and financial risk starting the cafe? Obsession. He told The New York Times:

We had records playing constantly, and young musicians performing live jazz on weekends. I kept this up for seven years. Why? For one simple reason: It enabled me to listen to jazz from morning to night.

The main records played in the bar were jazz from the 1950’s. You can listen below to set the scene.

Shortly after graduating from university in 1977, Haruki and Yōko moved the bar to Sendagaya in the center of Tokyo. Obsession struck again. Outside the new space, the Murakamis placed a big, smiling face of the Cheshire Cat; inside the bar, customers could admire cat figurines lying on all tables and on the piano, cat pictures, coasters, matchbooks, and paintings.3

Haruki began writing his first novel Hear the Wind Sing in 1979 at Peter Cat’s second location in downtown Sendagaya. He’d write for one or two hours in the kitchen after closing, and completed the novel in ten months. He submitted his manuscript for the Gunzo Prize for New Writers and won, setting his career in motion.4

The success of Murakami’s first two novels enabled the couple to give up the jazz bar. In 1981, he and Yoko sold the bar, and Haruki dramatically changed his lifestyle to devote himself to a new obsession that would take over decades of his life: writing.

Haruki Murakami has said his first novel came “out of nowhere.”

When he turned 29, he “got this feeling that I wanted to write a novel — that I could do it,” while sitting in Jingu Stadium watching a baseball game between the Yakult Swallows and the Hiroshima Carp. Dave Hilton, an American, came to bat, and according to an oft-repeated story, in the instant that Hilton’s bat hit the baseball, Murakami had a sudden realization that he could write a novel. “Hilton slammed Sotokoba’s first pitch into left field for a clean double. The satisfying crack when the bat met the ball resounded throughout Jingu Stadium. Scattered applause rose around me. In that instant, for no reason and on no grounds whatsoever, the thought suddenly struck me: I think I can write a novel.” He went home and began writing that night.5

But I’d argue that first novel, and Murakami’s later works, didn’t simply come “out of nowhere.” They are borne from his subconsciousness and intuition—the collage of all of his deep obsessions and the life experiences they brought him.

Murakami once told The New Yorker that if it hadn’t been for his years running Peter Cat, he would never have become a novelist. Until that day at the baseball game, he had never written a novel, but he had had time to observe, brood, and listen to customers while working behind the helm of the jazz bar. The bar’s stories filled his subconscious with ideas for characters and plots. He has also said that “the hard physical work” that it took to run the bar “gave me a moral backbone.” The rigor of running his own shop taught him the fortitude he’d need to sit down and write every day, devoting himself to a creative pursuit without the promise of success.

Meanwhile music gave him a template for how to write. Murakami said that when he began to write his first book, he “had absolutely no experience, after all, and no ready-made style at my disposal. I didn’t know anyone who could teach me how to do it, or even friends I could talk with about literature. My only thought at that point was how wonderful it would be if I could write like playing an instrument.” The young author approached creating his own style by mimicking musical structure. He wrote an essay in The New York Times about this musical approach to writing, remarking “Practically everything I know about writing, then, I learned from music.” He relates his writing process to the musical concepts of rhythm, harmony, and the accomplishment of finishing a performance. Here he is on rhythm:

Whether in music or in fiction, the most basic thing is rhythm. Your style needs to have good, natural, steady rhythm, or people won’t keep reading your work. I learned the importance of rhythm from music — and mainly from jazz.6

Today, he still allows great ideas and characters to emerge much like a jazz musician. He told The Guardian that he has never experienced writer’s block because his writing style is a “kind of a free improvisation.” He never plans, and never knows what the next page is going to be. “Many people don't believe me. But that's the fun of writing a novel or a story, because I don't know what's going to happen next. I'm searching for melody after melody. Sometimes once I start, I can't stop. It's just like spring water. It comes out so naturally, so easily."7

Because Murakami’s writing flows unobstructed from his subconscious, two of his core obsessions since childhood—music and cats—often appear in his stories. As he said in an interview: “whenever I write a novel, music just sort of naturally slips in (much like cats do, I suppose).” There are so many songs and cats in his novels that there are papers dedicated to the meaning behind them. Notably, in "Kafka on the Shore,” a character named Nakata is a simple-minded old man who can communicate with cats after a mysterious incident during his childhood. In "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,"a mysterious stray cat with a missing tail is featured as one of the enigmatic elements of the story. Contained within "1Q84," is an extended passage where we read, alongside the lead character, a short story called “Town of Cats.”

The most striking thing to me about Haruki Murakami’s life is his clarity. He knows what he loves and he has the motivation to design his life around those passions despite the risks.

He has said that he has known what he loved most in the world since childhood: “I loved to read; I loved to listen to music; and I love cats…Those three things haven't changed from my childhood.”8

Cats, books, jazz.

Cats, books, jazz.

Cats, books, jazz.

It’s as if these obsessions act as wells that he can tap over and over, offering him a source of seemingly limitless inspiration and energy.

Haruki’s approach to life reminds me of a reflection John Stuart Mill had after suffering a nervous breakdown at the age of 20. In metabolizing what helped him come back from this breaking point, the philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant extolled the virtue of passions in our lives, writing:

I never, indeed, wavered in the conviction that happiness is the test of all rules of conduct, and the end of life. But I now thought that this end was only to be attained by not making it [happiness] the direct end. Those only are happy (I thought) who have their minds fixed on some object other than their own happiness; on the happiness of others, on the improvement of mankind, even on some art or pursuit, followed not as a means, but as itself an ideal end. Aiming thus at something else, they find happiness by the way. 9

Mill is saying that caring about things other than yourself is essential if you want to be happy. That doesn’t have to mean devoting yourself to other people or a cause. It could mean caring deeply about jazz, baseball, running, cats, writing, or any and all sorts of obsessions. If you want to be happy, try less hard to be happy and instead immerse yourself in something you might be able to develop a deep interest in with time. Fill your life with things you find interesting, and your entire orientation might start to brighten.

Haruki Murakami’s life path is a testimony to the immense generative power of such obsessions. He once said: “I know what I love, still, now. That's a confidence. If you don't know what you love, you are lost." Murakami may be a strange obsessive, but he is the opposite of lost.

Perhaps each of us needs such simple, self-evident obsessions to keep us energized and inspired in life—passions we can name without hesitation, hobbies we can go deeper and deeper into as life progresses, instead of spreading ourselves thin across shallow interests.

But I can’t say I have ever had an obsession quite like Murakami’s, except, perhaps surfing. Do you?

I’ll close with an excerpt from an interview Murakami did with The New Yorker

I listen to music while I’m writing. So music very naturally comes in to my writing. I don’t think much about what kind of music it is, but the music is a kind of food to me. It gives me energy to write. So I write about music often, and mostly I write about the music I love. It’s good for my health.

The music keeps you healthy?

Yes, very much. Music and cats. They have helped me a lot.

How many cats do you have?

None at all. I go jogging around my house every morning and I regularly see three or four cats—they are friends of mine. I stop and say hello to them and they come to me; we know each other very well.

Writing, like running, is a solitary pursuit. You went from a very social life in a jazz club—where there were people around you all the time—to being alone in your study. Which is more comfortable for you?

I don’t do socialization much. I like to be by myself in a quiet place with a lot of records and, possibly, cats. And cable TV, to watch the baseball game. I think that’s all I want.

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Thank you to my mentor and friend for gifting me Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, at a crucial time in my life, and for helping me write this piece. Eric, you’re the undisputed greatest.

Heard the Wind Sing was translated into English but not available outside Japan at the author’s request.

https://thediplomat.com/2010/12/norwegian-wood-ok-and-pretty/

http://aflls.ucdc.ro/en/doc1/15%20CAT%20IMAGERY%20IN%20HARUKI%20MURAKAMI.pdf

https://www.soundoflife.com/blogs/people/the-unbreakable-bond-between-murakami-his-music

https://lithub.com/haruki-murakami-the-moment-i-became-a-novelist/

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/08/books/review/Murakami-t.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/may/17/fiction.harukimurakami

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/oct/14/haruki-murakami-1q84

John Stuart Mill, Autobiography (London: Penguin, 1989), 117.

1. AMAZING read

2. Holy moly that playlist has 350 hours and wow!

3. This was so inspiring, I didn't realize he was 29 when he started.

4. I love this newsletter so much

❤️ Utterly clarifying. "If you don't know what you love, you are lost."