Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts in your email inbox.

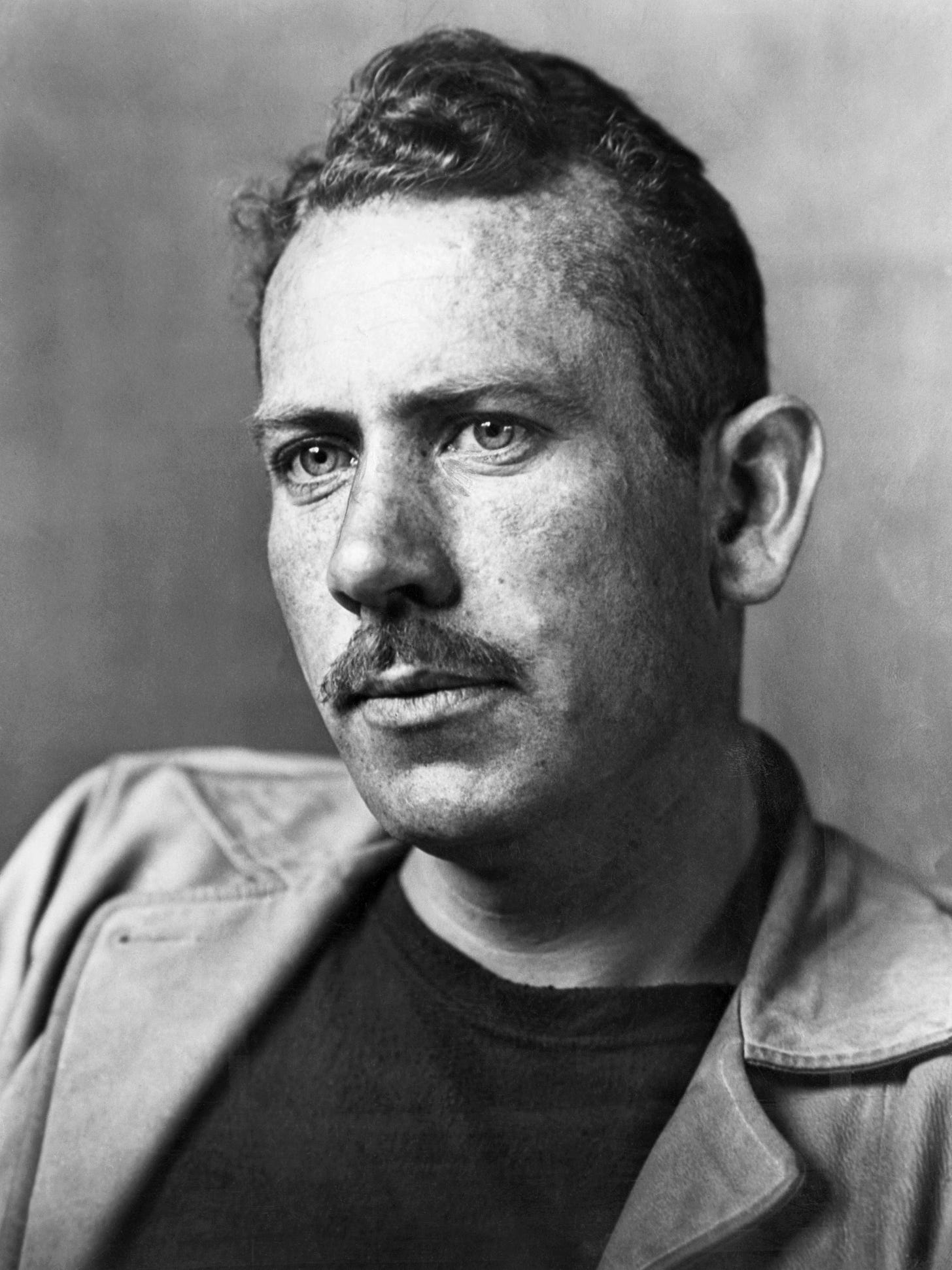

John Steinbeck is one of the giants of American letters. He has been called “the conscience of America” and is much-loved for bringing together “the human heart and the land” in his stories.

In his lifetime, John Steinbeck won most of the prestigious prizes an author could aspire towards: the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and more. Many of his books are still required reading at schools in the United States, especially in California. In total, he authored “22 novels, 12 nonfiction books, three film scripts and truckloads of newspaper articles and magazine essays”1 including East of Eden (1952), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which many believe to be his masterpiece. By the 75th anniversary of its publishing date, The Grapes of Wrath had sold 14 million copies.

John Ernst Steinbeck II was born in February 1902 in Salinas, California. He was the second of four children—and the only boy—born to John Steinbeck, Sr., the treasurer of Monterey County, and Olive Hamilton Steinbeck, a former teacher. The family was middle class, and Olive instilled in young John a love of reading and writing. By the age of fourteen, he had decided to be a writer and was spending hours “living in a world of his own making, writing stories and poems in his upstairs bedroom.”2

If you’ve read his books, you’ll know that John Steinbeck brought his childhood setting to life through his stories. Salinas sits near the central California coast and possesses some of the world's most fertile soil. On summer breaks from Salinas High School, John worked as a farm hand on the nearby Spreckels sugar beet farm.

After graduating from high school in 1919, John enrolled at Stanford University. Though he enjoyed his English classes, John found the college culture “pretentious and phony.”3 He studied at Stanford intermittently for six years, leaving campus often to take odd jobs in farms, factories or ranches. It was through Stanford that he met Ed Ricketts, and published his first story—about the marriage of a white girl and a Filipino worker. In 1925, he left Stanford for good to make his living as a writer, having never received a degree.

John Steinbeck wrote a handful of books to little acclaim before publishing Tortilla Flat at the age of 33. The story took shape during his years as a high school farmhand, and is set near his hometown of Salinas. Tortilla Flat won both commercial and critical success, and earned John his first Gold Medal from the California Commonwealth Club, a prize awarded for the best novel by a Californian.

Over the course of the next four years, John Steinbeck would publish Of Mice and Men and his greatest masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath, which brought him “overnight” fame and success. Louis Kronenberger compared The Grapes of Wrath to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in terms of its impact on the conscience of the American public, writing: “No novel of our day has been written out of a more genuine humanity, and none, I think, is better calculated to arouse the humanity in others.” The New York Times said that The Grapes of Wrath “touched off a national explosion of protest and indignation over the plight of the dispossessed.”4

Hollywood came calling to adapt both The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men into films, and John won a Pulitzer for The Grapes of Wrath. Before turning 40 years old, John Steinbeck had made it—an author enjoying critical acclaim, financial security, and public recognition.

John Steinbeck’s story seems like a literary slam dunk. A career path without friction, a pre-ordained star.

But the author would likely disagree with that description. He made it a point to return over and over to humility and groundedness, even inscribing a symbol of these qualities on his books and in his letters.

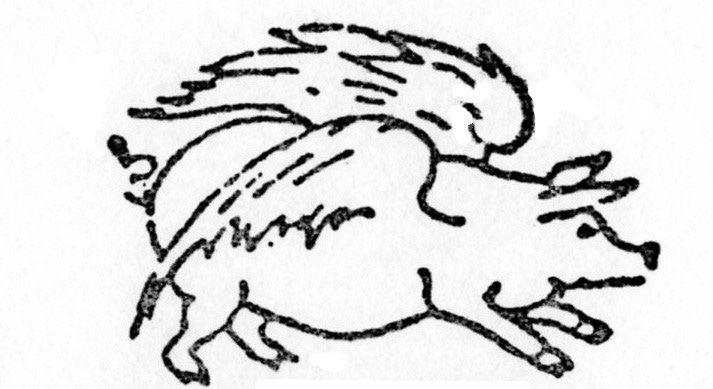

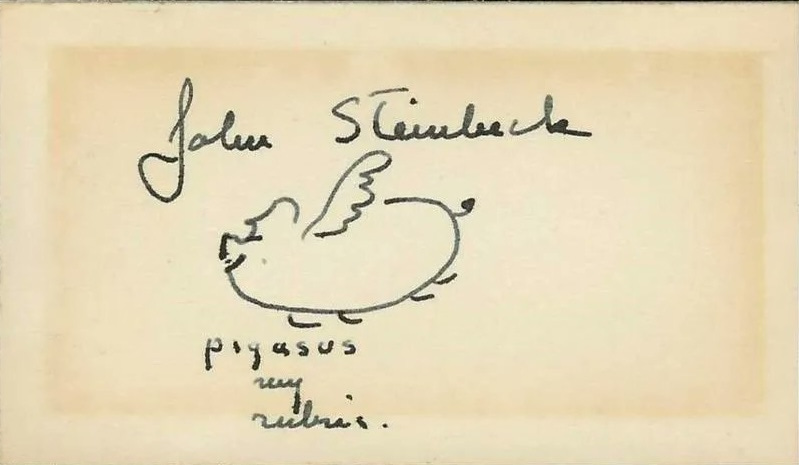

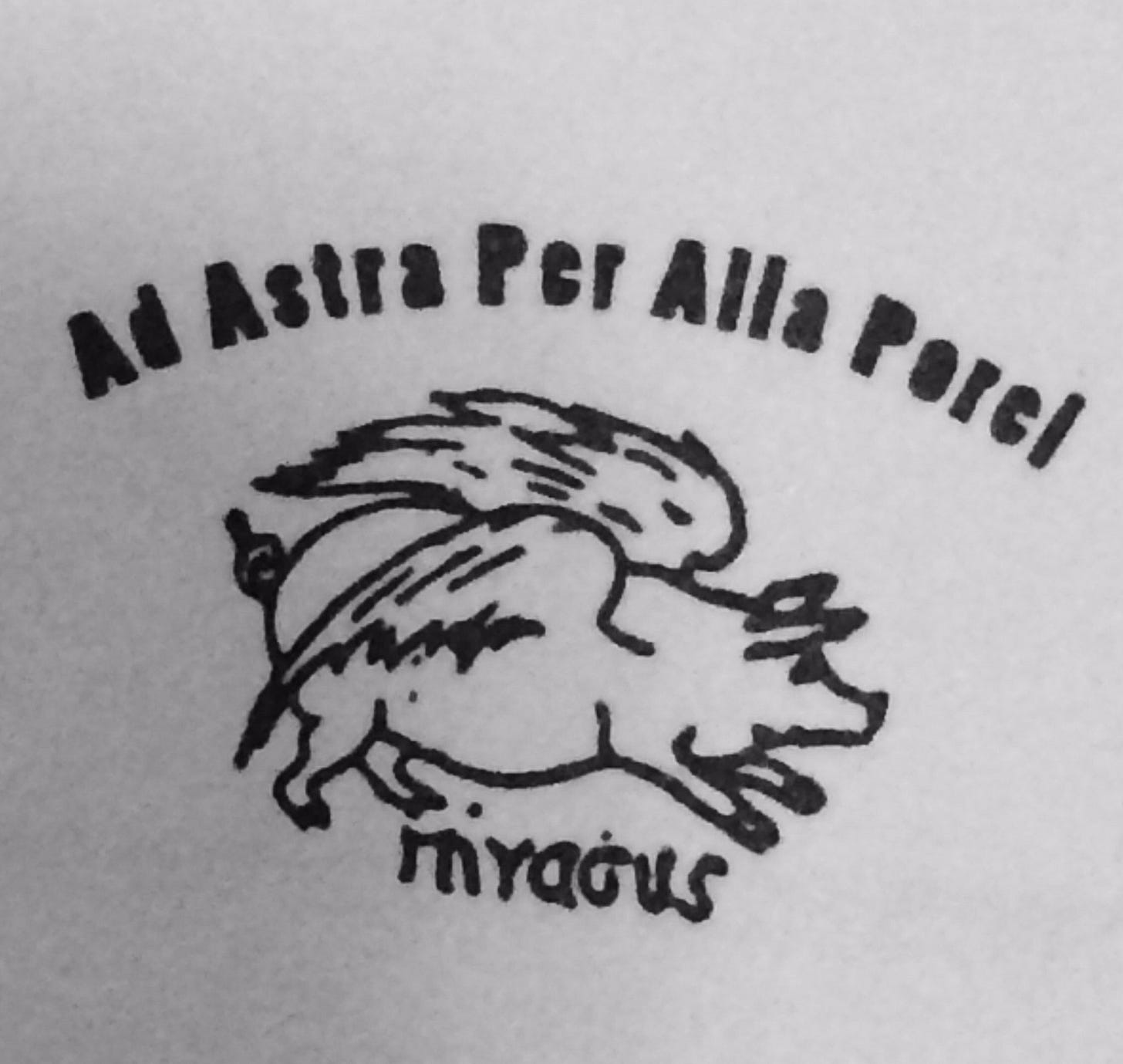

Meet the Pigasus.

Yes, a flying pig.

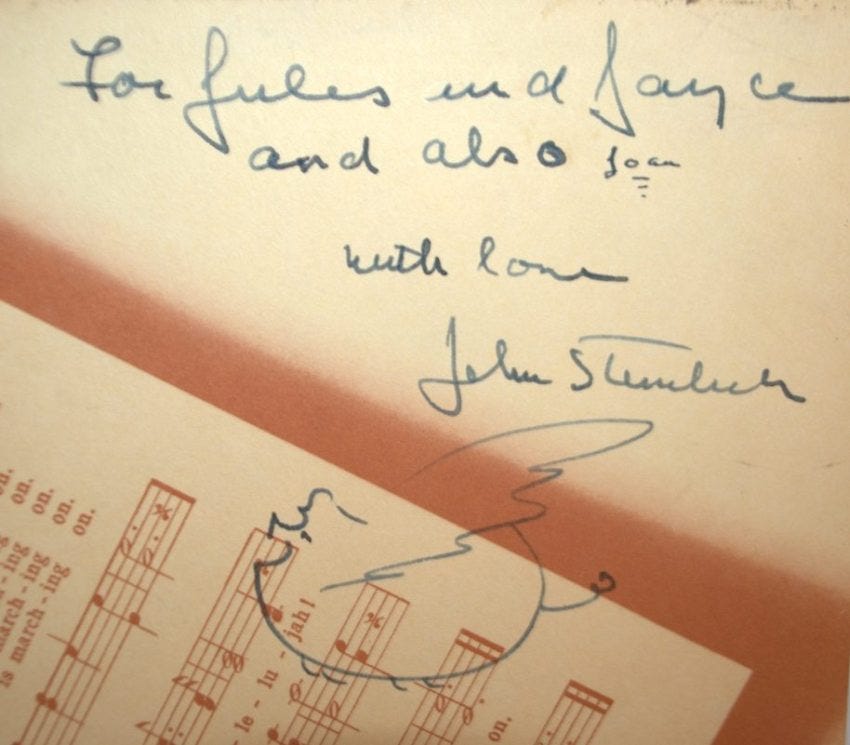

There’s an origin story floating around that John Steinbeck was once told by teacher or a literary professor in college that he would be an author “when pigs flew,” hence the stamp. While that story is hard to confirm, what’s not is that at some point the great novelist started to print a pig with wings into every book he published as an insignia. He even doodled a Pigasus onto his personal letters.

John referred to himself as a Pigasus to symbolize that his spirit was “earthbound but aspiring.” As one scholar explained: “He had great aspirations, dreams and ideals, but at the end of the day he was grounded. He saw himself more of a pig than a grand horse.”5 Inside his books, John Steinbeck included the Pigasus alongside a Dog Latin phrase: ad astra per alia porci, or “To the stars on the wings of a pig.” According to a letter from his wife Elaine:

The Pigasus symbol came from my husband’s fertile, joyful, and often wild imagination… John would never have been so vain or presumptuous as to use the winged horse as his symbol; the little pig said that man must try to attain the heavens even though his equipment be meager. Man must aspire though he be earth-bound.

This theme of human imperfection, and of striving and caring despite our flawed nature, was more than just a stamp and a personal philosophy for this great author. It would pervade his stories and fuel his very reason for being a writer.

John Steinbeck was known for “zealously guarding his privacy,” during his lifetime. He didn’t own a dinner jacket for many years, preferred the company of “people with no pretension” and “shunned award ceremonies; dodged interviews and declined as often as he could to pose for photographs.”6 As such, his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1962 is a rare recording of him directly conveying his philosophy of life. He seized the moment to lay out both his own purpose, and the purpose of every writer, to the audience. I can’t help but see the Pigasus in these words:

The ancient commission of the writer has not changed. He is charged with exposing our many grievous faults and failures, with dredging up to the light our dark and dangerous dreams for the purpose of improvement.

Furthermore, the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit – for gallantry in defeat – for courage, compassion and love.

In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally-flags of hope and of emulation.

I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man, has no dedication nor any membership in literature.

Man must try to attain the heavens even though his equipment be meager. Man must aspire though he be earth-bound.

Bonus: John Steinbeck’s dogs

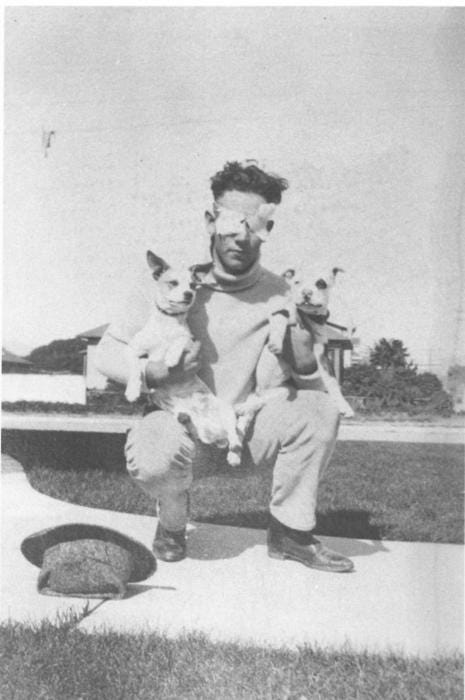

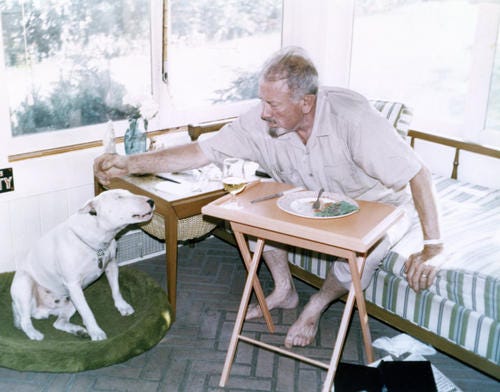

John Steinbeck spent his entire life with dogs. (You can see photos of them in the San Jose State archives here.)

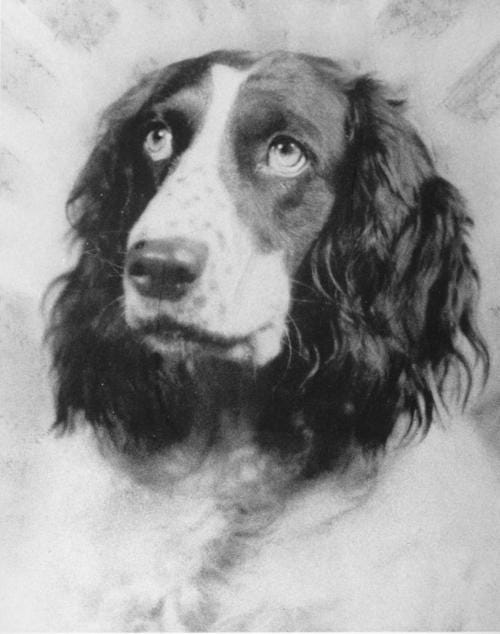

In fact, John even claimed that his Irish setter, Toby, ate part of his first draft of Of Mice and Men. John wrote to his editor:

My setter pup, left alone one night, made confetti of about half of my [manuscript] book. Two months work to do over again. It sets me back. There was no other draft. I was pretty mad but the poor little fellow may have been acting critically. I didn’t want to ruin a good dog for a ms. I’m not sure is good at all. He only got an ordinary spanking with his punishment flyswatter. But there’s the work to do over from the start.

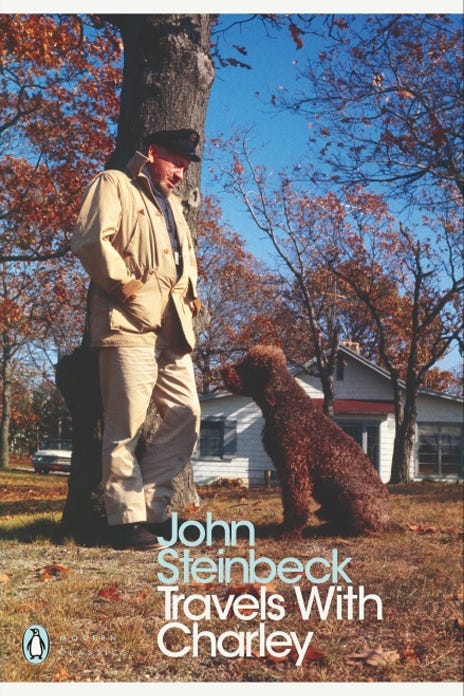

But if you’re a Steinbeck fan, one of his dogs will be more familiar than the rest: Charley.

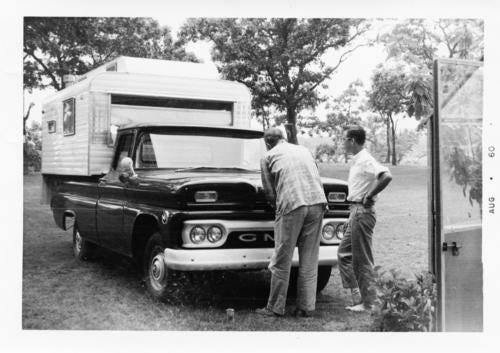

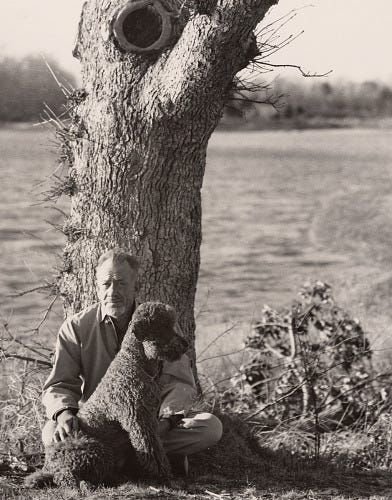

In the fall of 1960, at the age of 58, John Steinbeck decided to drive a 10,000 mile loop around the United States. He traveled in a pickup truck with trailer in the era before RVs and #vanlife.7 Because he’d lived in Europe and New York for many years by then, he came to believe that he “had not felt the country for twenty-five years” and worried that meant that he was growing too distant from his subject matter.

Thom Steinbeck, John’s oldest son, was 18 years old when his father left to wander the country. According to Thom, John actually believed he was dying when he decided to take this trip. “He went out to say goodbye”—to see his country one last time. The author’s younger son, also named John after his father and grandfather, once remarked that he was surprised that his stepmother even allowed the great author to travel. By this point, John Steinbeck was unwell, and had a heart condition that meant he could have died at any time.

As a companion on his grand adventure, John Steinbeck took Charley, his wife’s 10 year old standard poodle. In mid-1962, John published Travels With Charley just a few months before he accepted the Nobel Prize in Literature. It would be his last major work. Much of the book's charm emerges from his conversations with and observations of Charley ("In establishing contact with strange people, Charley is my ambassador"). Charley even makes appearances on a few of the covers.

The book reached #1 on the New York Times Best Seller list, where it stayed for one week, only to be replaced by Rachel Carson's Silent Spring.

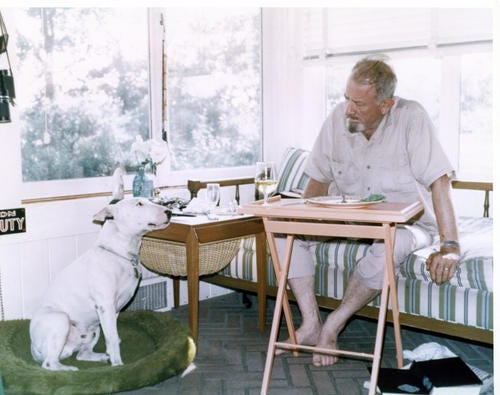

John Steinbeck would live eight more years after his grand tour, in the company of the final dog of his lifetime, a bull terrier named Angel.

Five years after John Steinbeck passed away, The Beach Boys sang about Steinbeck, Charley, and the author’s enduring relationship to their home state of California. Steinbeck and California, immortalized forever.

Have you ever been down Salinas way

Where Steinbeck found the valley?

And he wrote about it the way it was in his travelin's with Charley

And have you ever walked down through the sycamores

Where the farmhouse used to be?

There, the monarch's autumn journey ends

On a windswept cyprus tree

https://stanfordmag.org/contents/trailing-steinbeck

https://www.sjsu.edu/steinbeck/resources/biography/steinbeck-american-writer.php

https://studylib.net/doc/9240040/john-steinbeck-biography

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/12/21/76921334.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1077&context=spartan_daily_2017

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/12/21/76921334.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

https://www.deseret.com/2007/3/23/20008756/travels-with-charley-best-of-steinbeck-s-last-works

Thank you for Pigasus and Steinbeck’s gallery of dogs. “Charles le chien “ as Steinbeck called Charley, became my obsession after we adopted our first dog and I read TRAVELS for the first time. Charley was old and needed veterinary care on the journey. He died not long after. Although his appearances in the book are surprisingly brief, each one is lovingly observed. Charley’s pee is described as “a blessing” of the ground.

truly bodacious article ! Muchos Gracias !

Here’s link to an excellent article re the rescue of Rocinante

There is also another can round up - a truly rare tour inside the truck

including the details of the complete restoration process

http://www.thecamperbook.com/man-saved-john-steinbecks-van/