Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Kurt Vonnegut’s satirical and darkly humorous stories are required reading in America. The author wrote fourteen novels over a fifty-year career, including Cat's Cradle, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions.

As you might guess from the themes in his work, his early life wasn’t a walk in the park.

Kurt was born in Indiana on November 11, 1922. (Tomorrow would be his 101st birthday.) His family, once financially secure, lost nearly all of their wealth in just a few years. Their brewery was closed due to Prohibition, and then his father’s architecture practice collapsed in the Great Depression. The author later recalled his father withdrawing from normal life, and his mother becoming “depressed, withdrawn, bitter, and abusive.”1

Despite all of this, Kurt made his way to Cornell, but poor grades and a “satirical article” in the school’s newspaper cost him his place at the university. Because he was no longer eligible for deferment, he was sent off to serve in the army.

In May 1944, he returned home on leave for Mother's Day weekend to discover that his mother had committed suicide the night before he arrived by overdosing on sleeping pills.2

A few months later, he shipped off to Europe to fight in World War II. In December 1944, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge, where his division was overrun by the Germans. Over 500 of his peers were killed, and more than 6,000 were captured. Kurt was taken to a prison camp, and ended up living in a slaughterhouse in Dresden, Germany. He witnessed the terrible firebombing of the city, and survived by taking refuge in a meat locker three stories underground.3

Kurt returned from the war as a 22-year-old, and set out to finish his degree then kickstart a career in writing.

In his early thirties, his sister died of cancer. Soon after her husband passed away in a tragic train accident. Kurt adopted their three children. (He later adopted another child, making him the father of four adopted and three biological children—seven kids in total.)

It took nearly twenty years of struggling as a writer for him to reach commercial success. He published Slaughterhouse-Five as a 47-year-old, and it went to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list, thrusting Kurt Vonnegut into fame. Despite this success, he battled alcoholism and bouts of depression until the end of his life, and attempted suicide in 1984.

Read ’s review of Slaughterhouse-Five in the New Yorker here. Rushdie calls Vonnegut a “sad-faced comedian”

I’m sharing all of these brutal anecdotes because, for me, it makes the moments of lightness that Kurt Vonnegut created through his letters, speeches, and the spectacular photos of him we have on record all the more heroic. The writer once said: “It's a terrible waste to be happy and not notice it.” After researching his work and life, it appears to me that Kurt tried his best to notice small joys.

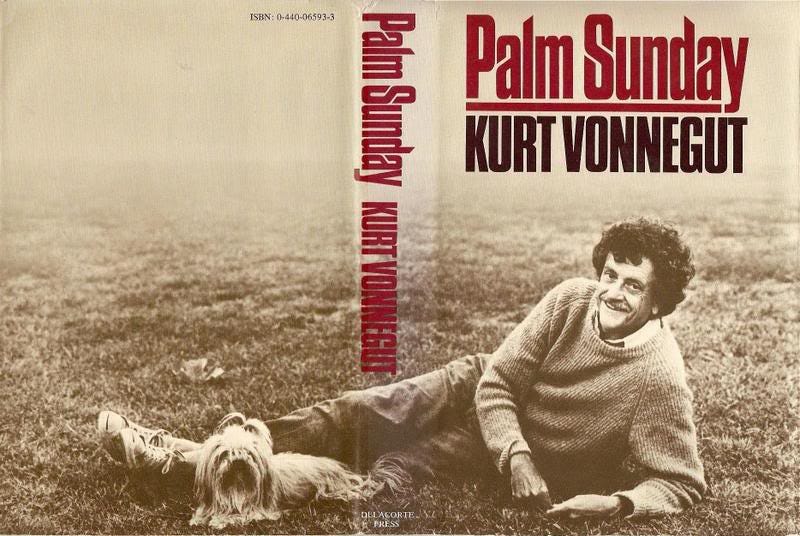

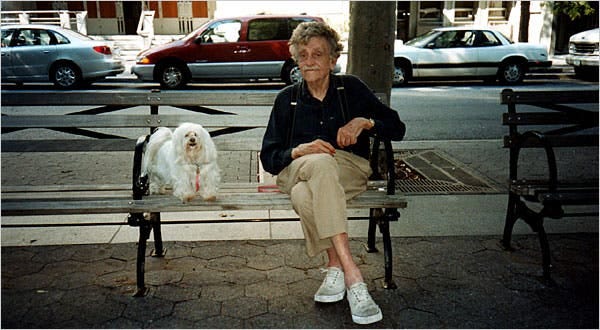

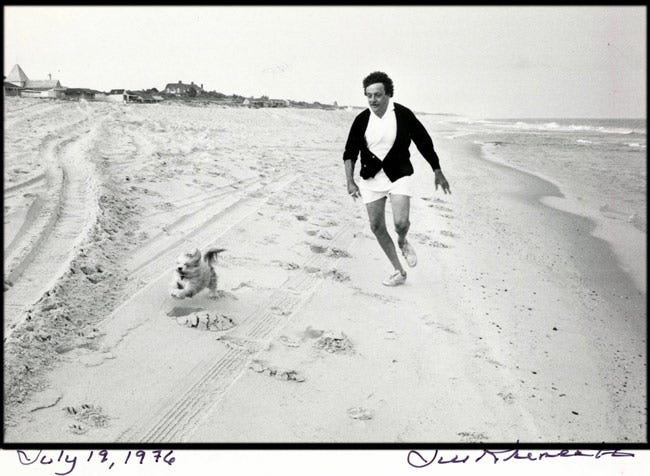

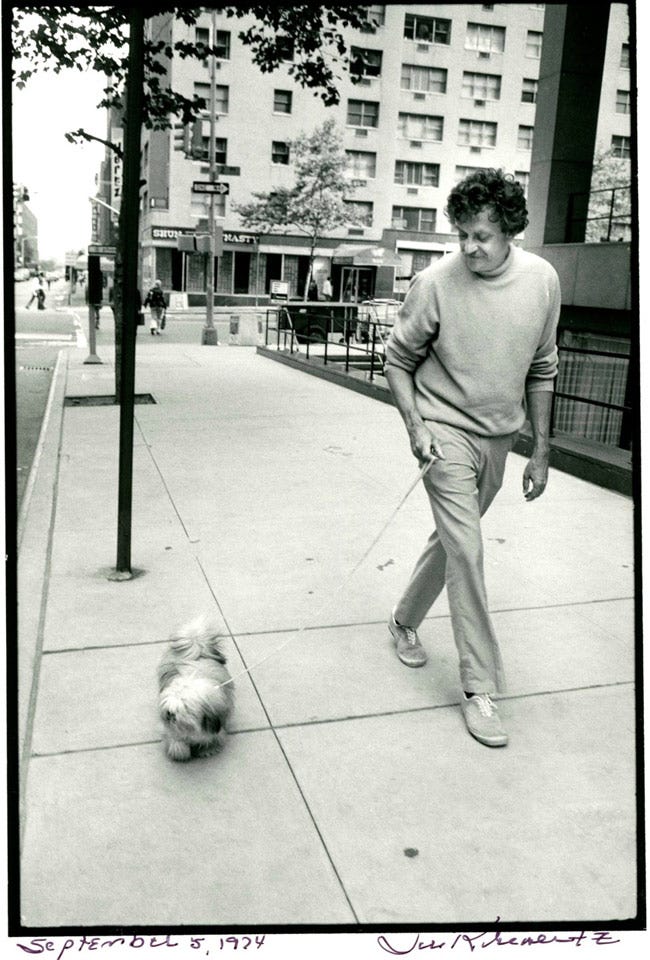

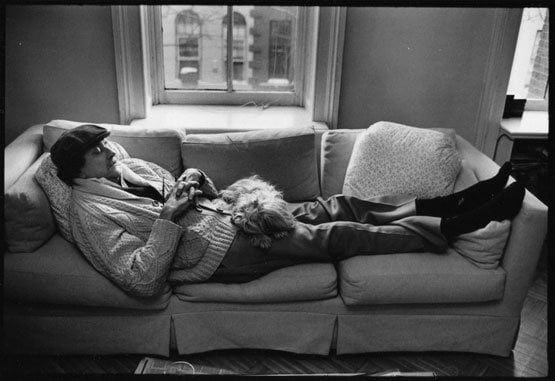

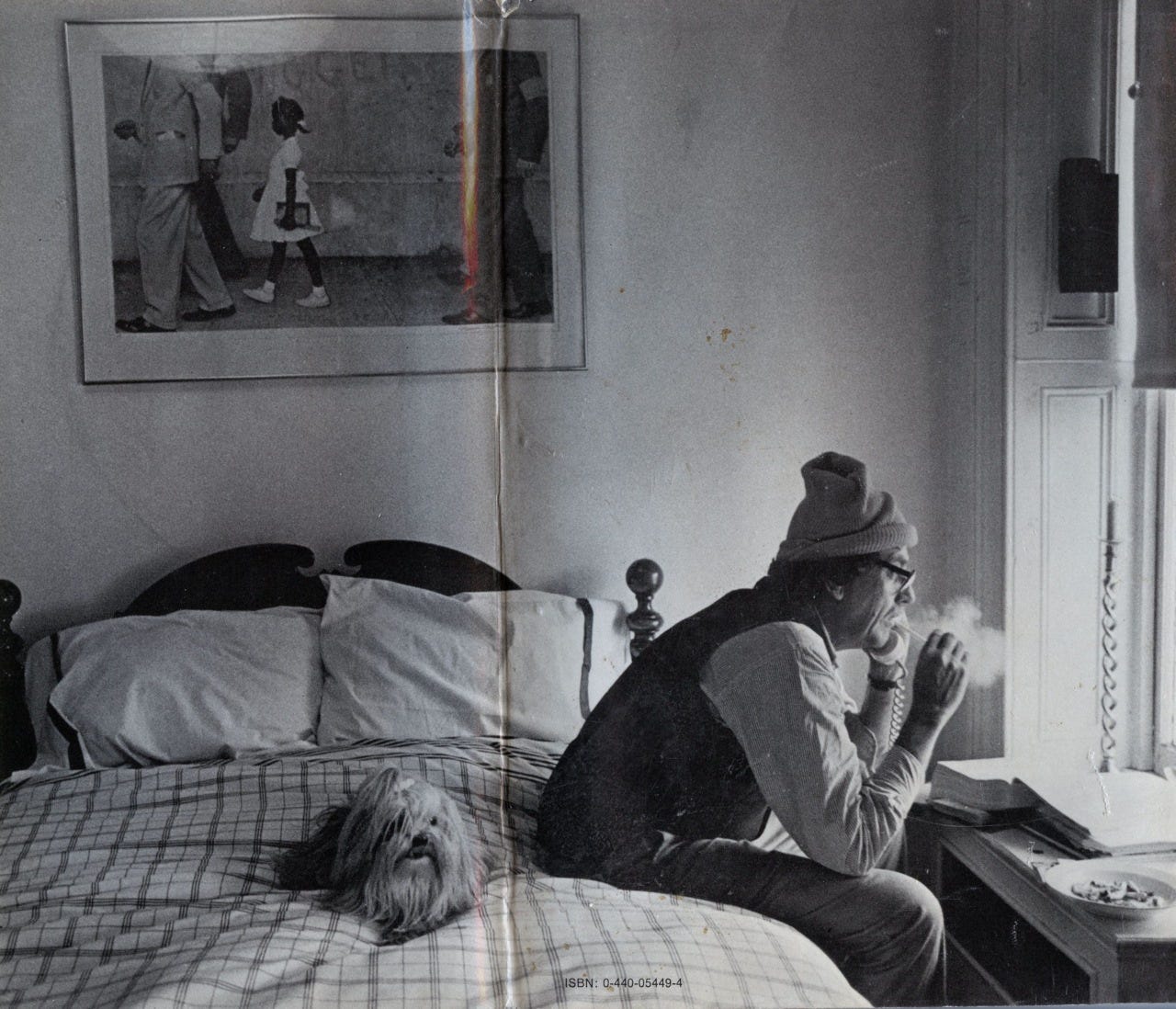

In 1979, Kurt married Jill Krementz, a tremendous photographer. She left us with images of Kurt in various states of bliss with their beloved dog, “Pumpkin.” This first image on the beach is my favorite photograph of an artist and their dog of the hundreds that I’ve come across writing Art Dogs so far.

Kurt Vonnegut was struggling with drinking and depression when some of these photographs were taken, and yet here he is, both playful and at ease. In a 1998 commencement speech at Rice, the writer told the crowd:

“When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, ‘If this isn’t nice, what is?’”

When I look at the scenes above, I can imagine Kurt Vonnegut turning to his wife behind the lens and saying his own words back to her: If this isn’t nice, what is?

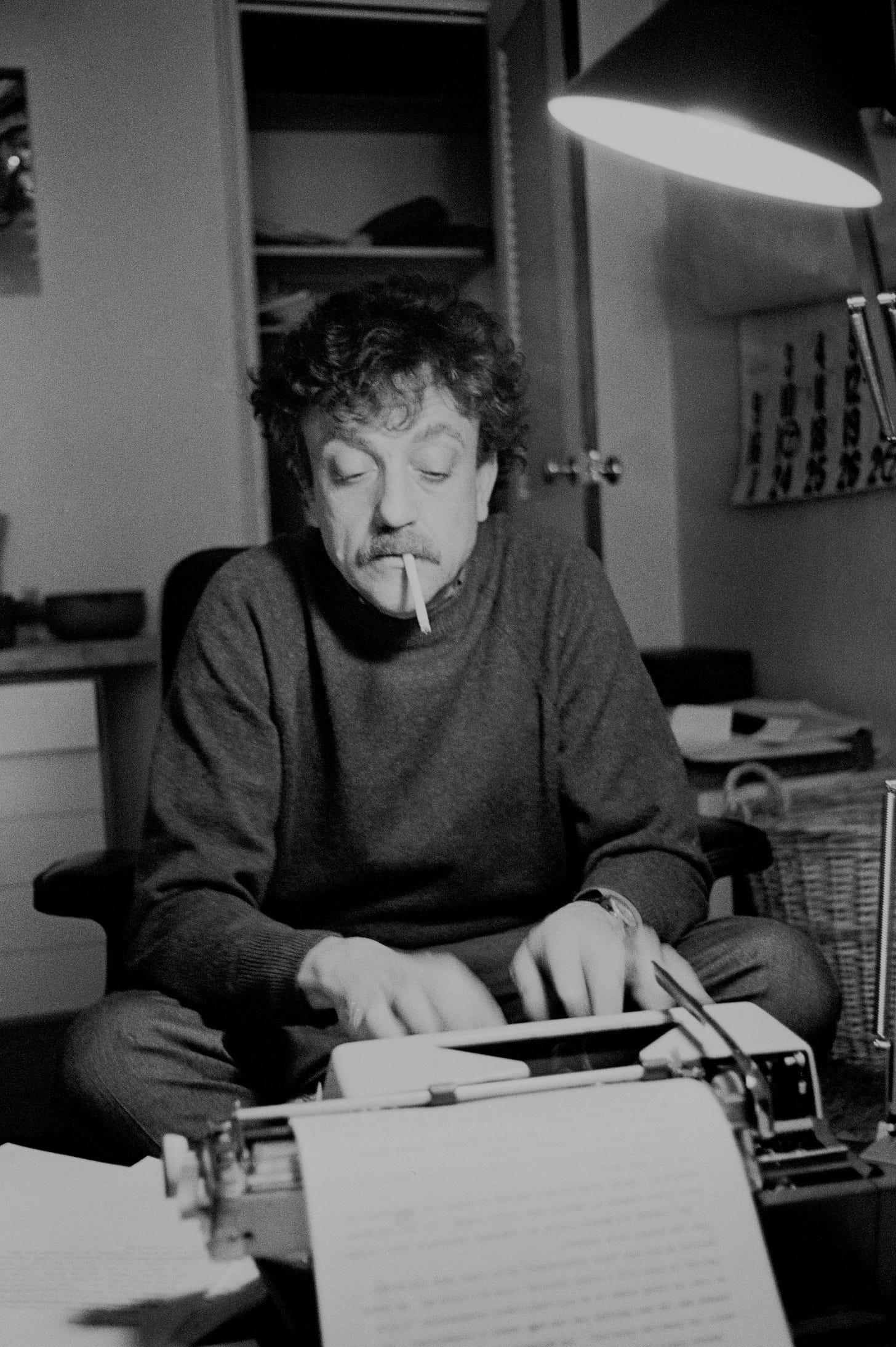

One of my favorite Kurt Vonnegut passages is, surprisingly, from a September 1996 Technology issue of Inc. Read it all the way through. I promise you won’t regret it.

I work at home, and if I wanted to, I could have a computer right by my bed, and I’d never have to leave it. But I use a typewriter, and afterwards I mark up the pages with a pencil. Then I call up this woman named Carol out in Woodstock and say, ‘Are you still doing typing?’ Sure she is, and her husband is trying to track bluebirds out there and not having much luck, and so we chitchat back and forth, and I say, ‘OK, I’ll send you the pages.’

Then I’m going down the steps, and my wife calls up, ‘Where are you going?’ I say, ‘Well, I’m going to go buy an envelope.’ And she says, ‘You’re not a poor man. Why don’t you buy a thousand envelopes? They’ll deliver them, and you can put them in a closet.’ And I say, ‘Hush.’ So I go down the steps here, and I go out to this newsstand across the street where they sell magazines and lottery tickets and stationery. I have to get in line because there are people buying candy and all that sort of thing, and I talk to them. The woman behind the counter has a jewel between her eyes, and when it’s my turn, I ask her if there have been any big winners lately. I get my envelope and seal it up and go to the postal convenience center down the block at the corner of 47th Street and 2nd Avenue, where I’m secretly in love with the woman behind the counter. I keep absolutely poker-faced; I never let her know how I feel about her. One time I had my pocket picked in there and got to meet a cop and tell him about it. Anyway, I address the envelope to Carol in Woodstock. I stamp the envelope and mail it in a mailbox in front of the post office, and I go home. And I’ve had a hell of a good time.

And I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you any different.

I bet “farting around” sustained Kurt Vonnegut through the suffering in his life, evening out his highs and lows with small moments of delight, motion, and serendipity. Moments worth savoring.

And I bet his dogs were key co-conspirators in farting around—going for runs on the beach, indulging in naps on the couch or wandering strolls down Manhattan avenues.

Fittingly, in the last words of advice the great writer ever wrote for an audience, he prescribes a dose of dog as an antidote to the torment of our modern lives:

How should we behave during this Apocalypse? We should be unusually kind to one another, certainly. But we should also stop being so serious. Jokes help a lot. And get a dog, if you don’t already have one.

I guess it’s time for me to get a dog.

Until next time, Bailey

Sharp, Michael D. (2006). Popular Contemporary Writers. Vol. 10. Marshall Cavendish Reference.

Farrell, Susan E. (2009). Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing.

Boomhower, Ray E. (1999). "Slaughterhouse-Five: Kurt Vonnegut Jr". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History.

What a great issue 👏 I really admire Vonnegut.

P.S. there's a quote that consistently resonates with me:

🌱💧🎨

“To practice any art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow. So do it.”

~ Kurt Vonnegut

This is just the best! Always loved Kurt, now I feel like I know him better; more as a complete, real human being.

Thank you for this, I am sure I won't read anything better than this piece today. Plus I know I will be more mindful, pausing to experience the simple passing happinesses.