Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Pedro Almodóvar has been called the most important Spanish director since Luis Buñuel. His films are marked by melodrama, bold color and glossy décor, and complex narratives. He launched the careers of world-famous actors, including Antonio Banderas and Penélope Cruz, and his films have both a cult following and industry recognition. Pedro has received a Golden Lion, nine Academy Award nominations—winning twice for All About My Mother (1999) and Talk to Her (2002)—and been the subject of retrospectives at the world’s most important cultural institutions, including MoMA.

To set the tone, here’s a scene from Talk to Her with one of my favorite musicians, Caetano Veloso.

Pedro Almodóvar Caballero was born in 1949, in Calzada de Calatrava, a small town in central Spain. He described his hometown as “highly conservative, extremely backward.” From the start, he felt he didn’t fit in. “My parents were effectively living in the 19th century and they gave birth to a son who was almost like a 21st-century child.”1

He grew up mostly in the company of women, and began to adore them at an early age. He sees women as a singular force. “It was because of women that Spain survived the postwar period,” he told The New Yorker.2 While the men worked, the women “nurtured the children and dealt with births, relationships, and deaths,” which Pedro came to call los problemas reales. In a 1999 interview with Guillermo Altares, he described “the Spanish father” in contrast as “oppressive, repressive.” Critics have described his work as a “Cinema of Women.”

Pedro has said that many of his characters were inspired by his mother. “She had the capacity to fake things, fake things in order to solve problems,” he said, explaining that as opposed to the men in his family, the women “would resolve situations with the greatest naturalism, with the greatest ease, they would just fake that certain things were happening in order to protect us as children, and they did it with the greatest conviction. Life is filled with these miniature plays, scenarios, where people are forced to act or fake, and women are naturally born actresses.” 3

Watch Pedro Almodóvar’s interview with MoMA below for more on his “Cinema of Women”

Pedro’s parents sent him to Catholic boarding school, but he hated the “authoritarian” education. Some priests sexually abused his peers, which young Pedro was aware of at the time.4 He stopped confessing, and he and his brother started going to the movies instead.

By the age of 17, Pedro knew he wanted to make films. He came home from Catholic school one day and told his parents that he was moving to Madrid, leaving despite their disapproval. Upon arriving in Madrid in the late 1960s, Pedro took jobs as a disc jockey, an extra in movies, and an office assistant. He bought a Super 8 camera and began to shoot short films without any budget, writing the entire script himself. He projected these films for friends in bars, discos, and art galleries.

At the time, Franco was still in power in Spain, though he was aging and his grip loosening. An artistic and musical movement called La Movida started spreading in Madrid that took inspiration from punk and New Wave movements in England and America. Pedro became a key figure in this scene, initially as a singer (see the video below) then as a “frustrated novelist,” which is how he still describes himself today.

Once Franco died, the group flourished. Pedro describes his time with La Movida as “a dream come true, the best experience of his life.” And notes that it was only possible because he had fled his hometown and Franco was out of power. “Franco had to die so that I could live.”5 Repression transformed into expression.

Pedro scrapped together the money for his first full movie, “Pepi, Luci, Bom,” which he shot on weekends over thirteen months. Filming would halt when they ran out of money, which was mostly spent on food and alcohol for the cast and crew. (“This was logical,” he said, on a Spanish talk show. “The people had to be content.”)

Despite mediocre reviews, “Pepi, Luci, Bom,” became “a staple of late-night Madrid—a ‘Rocky Horror Picture Show’ for the Spanish—and highly profitable.”6 Producers began wooing Pedro, and he set out to work on a feature film.

“Camp makes you look at our human situation with irony” — Pedro Almodóvar

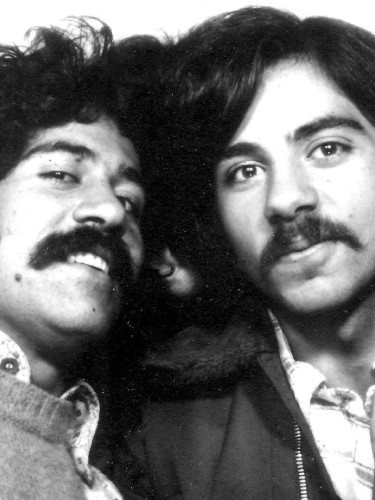

In 1985, with his brother Agustín’s help as his business counterpart, Pedro set up his own production studio called El Deseo. Of Agustín and El Deseo, Pedro has said: “I owe Agustín the independence and liberty that I enjoy as a director. It’s completely without precedent. Not even Scorsese himself has been able to do that.”

Agustín explained to The New Yorker that his sole purpose at El Deseo is to “help Pedro make the movie he wants.” Though Agustín was trained as a chemistry teacher, he chose to devote himself to his brother’s career because he felt his relationship with Pedro “was the crucial thing in his life.” He speaks about his brother’s “genius” and “brilliance” regularly, and you can see that admiration immediately if you peek at Agustín’s prolific Twitter profile: https://twitter.com/AgustinAlmo.

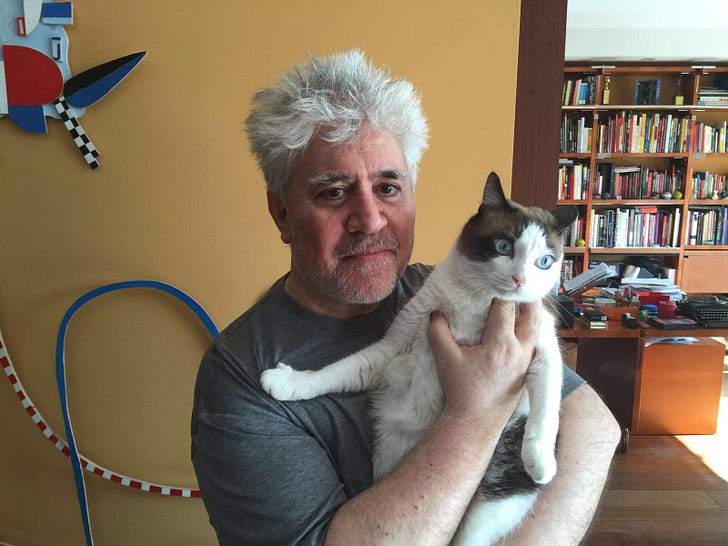

It was there that I unearthed what might be the only photo of Pedro Almodovar with one of his two cats in 2016.

Pedro Almodóvar’s apartment in Madrid today is close to the Malasaña district, where the artists of La Movida once pulsed and thrashed away their evenings. Gentrification has taken hold of Malasaña, and the neighborhood is now “thoroughly sanitized” of its raucous past.

Pedro lives alone, except for his books, 3,000 DVDs, and his cats, Pepito and Lucio.7 He has said that “a cat is the right pet for a selfish writer,” explaining that “if you dedicate your life to the movies, to writing or painting, the life you can offer another person is very precarious. I couldn’t have the strength or the right to ask another person to accept this sort of life.”8 Despite the devotion he has with his brother and had with his mother, and occasional rumors in the press, Pedro Almodóvar is steadfast in saying that he has no romantic partner. (He came out at age 34.)

Instead, Pedro’s life, and his family’s life, is organized to support his “addiction,” to storytelling. In 2019, he shared more in an interview:

“It’s an addiction, the need to tell stories… Perhaps this is the reason I haven’t developed any other facets of my life. Quite the opposite, I think I’ve cut back. So I’ve now reached the point where film is the only thing that makes me feel whole. Cinema is the only thing I have. It’s finished up being both the end and the means for me… Personally, I’ve got used to not needing other people. I’ve let them go. I’ve cut them off. I suppose I could get them back if I wanted. But I’d need a spur. I’d need a reason.”9

Philosopher

recently wrote about the concept of a “sinthome” in a reflection on the great writer Patricia Highsmith. Slavoj believes that writing acted as a sinthome for Highsmith, a term defined by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan in the mid 1970s. The sinthome is an object or practice that provides the continuity that holds a person’s life together, such that if you remove it, that person’s entire would fall apart. For Highsmith, writing was “the knot” that held her universe together, “the artificial symbolic formation through which she maintained a minimum of sanity by conferring on her tumultuous experience a narrative consistency.”It strikes me that the Almodóvar family’s story is the story of sinthome. Pedro’s career is his brother, Agustin’s, sinthome. Making movies is Pedro’s. “If I am not involved in a film, my life feels sad,” Pedro told El Pais. “That leaves me in a permanent state of anxiety.”

The problem is that, when overindulged, these sinthomes can isolate and repress us. Pedro Almodóvar told writer Xan Brooks in an interview in 2019, “If I could have looked ahead and seen myself now, I don’t think my view of myself would be positive. I wouldn’t like what I’ve turned into. I’d look over and think: ‘Who’s that lonely solitary old man?’” Working obsessively has pulled the director away from real life.

In his 2019 profile of Pedro Almodóvar in The Guardian, Xan Brooks asks: “Is this where most great artists wind up: in an ivory tower, contemplating the stars?” Xan argues that the great director’s current lifestyle “runs counter to the abiding spirit of [his own] work, which has always been about noise, colour, incident; the rub and thrust of bodies in close quarters.” Put another way, Pedro Almodóvar’s films are fundamentally animated by los problemas reales that result from actually engaging in the messy complexity of human communities and relationships.

What happens when an artist like Pedro Almodóvar drifts too far from los problemas reales in his own life? One critic, Kyle Turner, asserts that Pedro’s recent work is “stewing in nostalgia,” but not substance:

“If his new short, Strange Way of Life (2023), is any indication, each subsequent work in [Pedro Almodovar’s] filmography is proving the broth is losing a layer of flavor.…as a wispy whole, it’s more like something that will be blown away like footprints in the sand. Its attractive desert vistas notwithstanding, the short is about as substantial as one would expect from a glorified commercial by a haute couture house.”10

Ouch!

Time will tell if Pedro Almodóvar’s “broth” will only continue to lose its flavor.

I, for one, haven’t lost faith in him. I believe him to be one of the great artists of our generation, and he has all that he needs in his muscles and in his memories to turn his latest bout with repression into expression. Here’s to hoping that this great artist can find his way back to the source—to los problemas reales.

Thank you to my dear friend Isabelita Virtual for helping me fact check and write this post.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/12/05/the-evolution-of-pedro-almodovar

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/02/movies/pedro-almodovar-and-his-cinema-of-women.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CShe%20had%20the%20capacity%20to,order%20to%20protect%20us%20as

ibid. In 2007, he told GQ that he “could almost literally see their hands dirtied with sperm.”

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/aug/11/pedro-almodovar-interview-pain-and-glory-deep-down-i-know

https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2016/03/18/inenglish/1458309364_369885.html. His first cat was given to him in 2010, during the filming of “The Skin I Live In,” in Toledo. Some children left a cat with one of the people working on set, asking that it be called Lucía by its next owner. The cat was passed on to Almodóvar, who realized it was a boy cat. “We had an instant sex change!” Almodóvar joked. “He was a stray cat who is now king of the house and doesn’t want anything to do with the street.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/12/05/the-evolution-of-pedro-almodovar#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWe%20had%20an%20instant%20sex,another%20person%20is%20very%20precarious.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/aug/11/pedro-almodovar-interview-pain-and-glory-deep-down-i-know

Beautifully written! thank you!

Wow. I love this, and all the links too. I never knew any of that of his private life, so interesting the difference between our internal and external worlds. I can't wait to see his adaptation of Lucia Berlin.