Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Toni Morrison is perhaps the greatest writer in American history. In her lifetime, she published 11 novels. She also created plays, an opera, and with her son Slade, she co-authored a number of books for children. Today, Toni Morrison is required reading in schools across the United States. She was awarded a Pulitzer Prize and she was the first African-American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

But she didn’t write her first novel until she was 39 years old, by then a divorced mother of two boys. As Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah wrote: “She wasn’t born Toni Morrison. She had to become that person.”1

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Wofford in Ohio in 1931. Her family lived in at least six different apartments over the course of her childhood. (One of their apartments was burned down by the landlord when the Woffords couldn’t pay the rent, which was four dollars a month.) Here’s how the New Yorker described the unassuming home and town she was born into:

No. 2245 Elyria Avenue in Lorain, Ohio, is a two-story frame house surrounded by look-alikes. Its small front porch is littered with the discards of former tenants: a banged-up bicycle wheel, a plastic patio chair, a garden hose. Most of its windows are boarded up. Behind the house, which is painted lettuce green, there’s a patch of weedy earth and a heap of rusting car parts. Seventy-two years ago, the novelist Toni Morrison was born here, in this small industrial town twenty-five miles west of Cleveland, which most citydwellers would consider “out there.” The air is redolent of nearby Lake Erie and new-mown grass.2

At twelve years old, Chloe decided to convert to Catholicism. She took Anthony as her baptismal name, after St. Anthony, and her friends began to call her Toni. By junior high, her talents were evident. A teacher sent a note home to her mother: “You and your husband would be remiss in your duties if you do not see to it that this child goes to college.”3

At Lorain High School, Toni participated in debate, yearbook, and drama club. Although Oberlin College was just 30 minutes from home she decided to go to Howard University in Washington, D.C. “I want to be surrounded by Black intellectuals,” she said. Her parents took on extra work to pay her tuition.

Her dad, George Wofford took a second union job, which was against the rules of U.S. Steel. In the Lorain Journal article, Ramah Wofford remembered that his supervisors found out and called him on it. “ ‘Well, you folks got me,’ ” Ramah recalled George’s telling them. “ ‘I am doing another job, but I’m doing it to send my daughter to college. I’m determined to send her and if I lose my job here, I’ll get another job and do the same.’ It was so quiet after George was done talking, you could have heard a pin drop. . . . And they let him stay and let him do both jobs.” To give her daughter pocket money, Ramah Wofford worked in the rest room of an amusement park, handing out towels. She sent the tips to her daughter with care packages of canned tuna, crackers, and sardines.4

After graduating from Howard in 1953—when segregation was still rampant in America, D.C. included—she earned a master’s degree from Cornell in American literature. Her thesis was titled “Virginia Woolf’s and William Faulkner’s Treatment of the Alienated.” She said she saw in their work “an effort to discover what pattern of existence is most conducive to honesty and self-knowledge, the prime requisites for living a significant life.”5

Toni then went back to Howard to teach, and soon married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect. She joined a writing group, and began writing a story about a little Black girl, Pecola Breedlove, who wanted blue eyes. When Morrison read the story to the group, a peer reportedly turned to her and said, “You are a writer.”

While pregnant with her second son, her marriage to Harold fell apart. Toni left Howard and returned home to Ohio, where she found a job listing that would change her life: a position with L. W. Singer, a division of Random House. In 1965, at thirty four years old, she got the job and moved to New York, a solo parent with two babies.

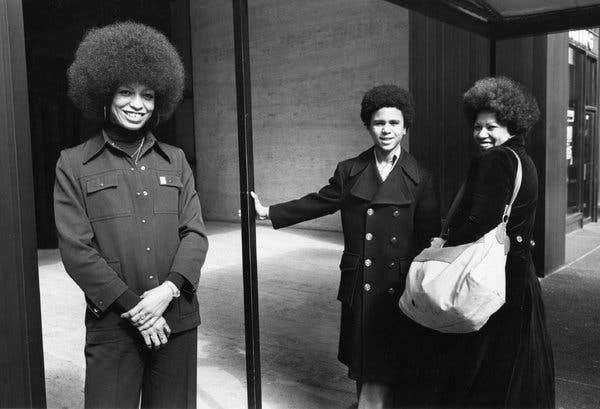

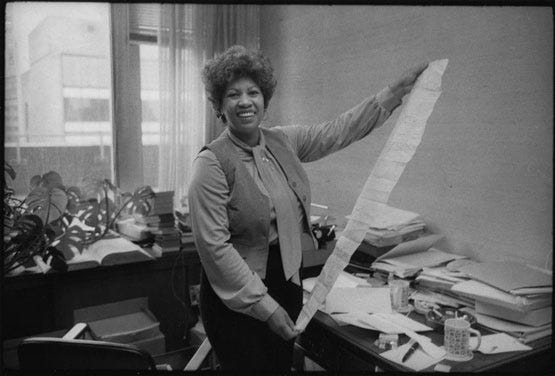

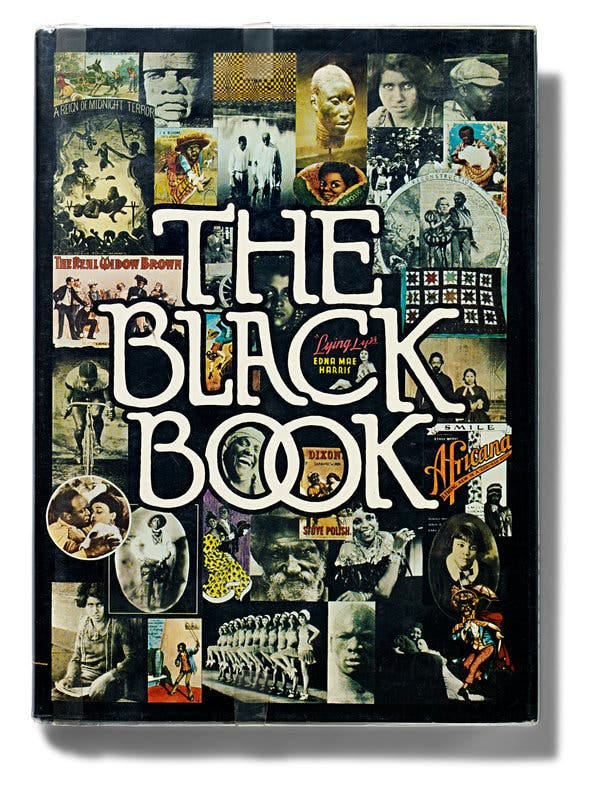

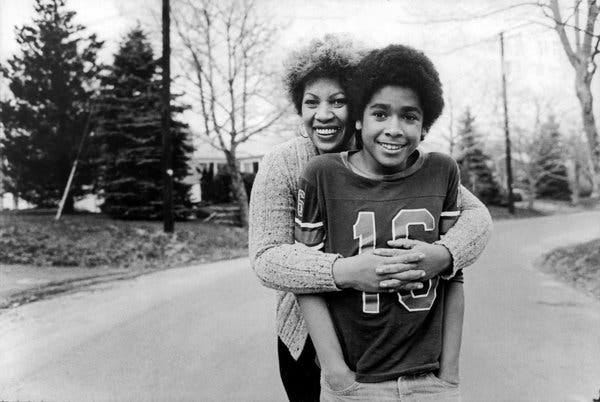

Toni became the first Black woman to work as an editor at Random House. Through the 1960s and 1970s, she acted a pivotal supporter of Black writers-as a friend would say, she was “not a Black editor but the Black editor.”6 She published Gayl Jones and Toni Cade Bambara, and edited James Baldwin, Lucille Clifton, and many more. She pushed Muhammad Ali, while still at odds with the United States government over his draft status, to write an autobiography, and worked closely with Angela Davis to do the same.7 The earliest photos of her come from this era where she participated in culture not as a lauded author but as an editor and began to receive press for her own talents.

During these years, she rose early to write before going into work, and before her sons woke up. She published “The Bluest Eye” (1970), “Sula” (1974), and “Song of Solomon” (1977) while working in publishing, teaching part-time at Yale, and raising two children.8

“What was driving me to write was the silence—so many stories untold and unexamined. There was a wide vacuum in the literature,” Morrison later said. “I was inspired by the silence and absences in the literature.”9 She told The Dictionary of Literary Biography: “I look very hard for Black fiction because I want to participate in developing a canon of Black work.”

The relationships that Toni built during this era are worth pausing to reflect on. She sustained other Black voices, particularly Black women she published and worked with, and in turn they sustained hers. In 2003, she reminisced about this period in her life with the New Yorker:

“Single women with children. If you had to finish writing something, they’d take your kids, or you’d sit with theirs. This was a network of women. They lived in Queens, in Harlem and Brooklyn, and you could rely on one another. If I made a little extra money on something—writing freelance—I’d send a check to Toni Cade with a note that said, ‘You have won the so-and-so grant,’ and so on. I remember Toni Cade coming to my house with groceries and cooking dinner. I hadn’t asked her.”

The mutual support was practical, and also intellectual. The books that came from Toni’s circle of women in this period led to a rebirth of Black women’s fiction.10

wrote about this writing group, called The Sisterhood, earlier this year. She shared that this group of writers served “as a critique of the idea that there could be only one great Black woman writer in a generation. The Sisterhood insisted on multiplicity.”

Kaitlyn went on:

A generation earlier, James Baldwin and Richard Wright had circled each other warily, cognizant of the scrutiny of the larger white literary world. The Sisterhood, at least at its start, rejected the myth of the one and only. This is evident in Morrison’s work as an editor at Random House, where she published works by Angela Davis and Henry Dumas, and Walker’s promotion of fellow Black female writers to publications and editors. It’s there in members’ archived syllabi, where we can see them assigning one another’s work to their students, long before that work was considered part of any canon.”

Emerging from this community, in 1977, Toni published “Song of Solomon,” which brought her national acclaim. At 46, she finally had the financial freedom to write full time, and she took full advantage of it.

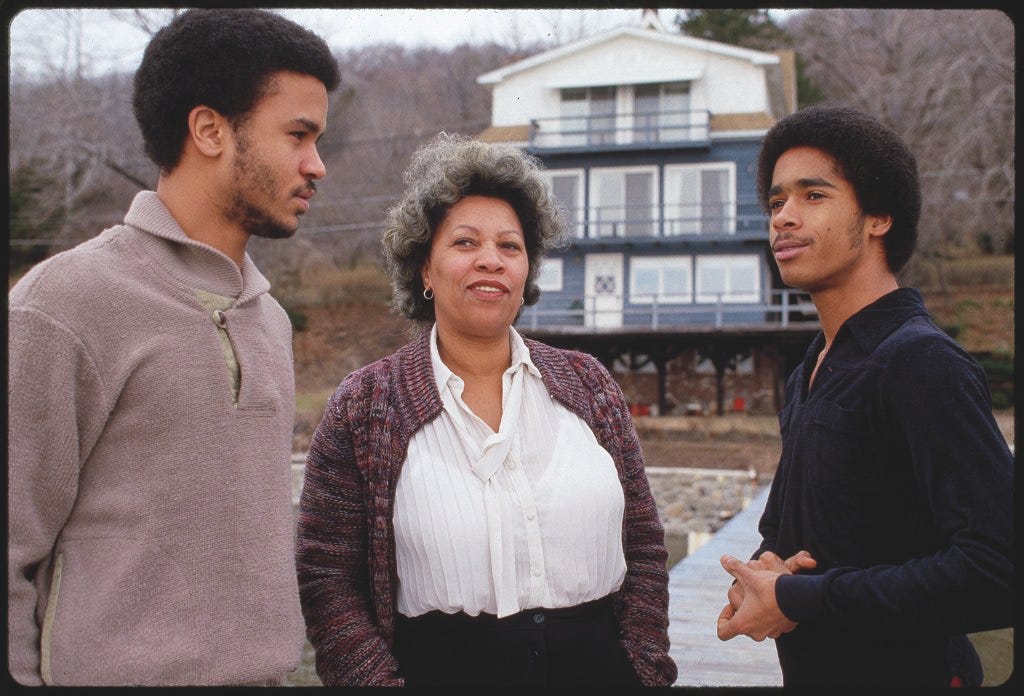

As Toni’s writing career took off and her boys reached their high school years, she purchased a converted boathouse on the banks of the Hudson River in Grand View-on-Hudson. She would spend most of her time there for the next four decades.

When Toni moved upstate, she surely traded some of her daily access to mutual support and intellectual relationships for the nature, space, and time that would allow her to write incredible works of art. It was from this home that she wrote Tar Baby and Beloved, the novel that would win her a Pulitzer and bring her work into the mainstream.11

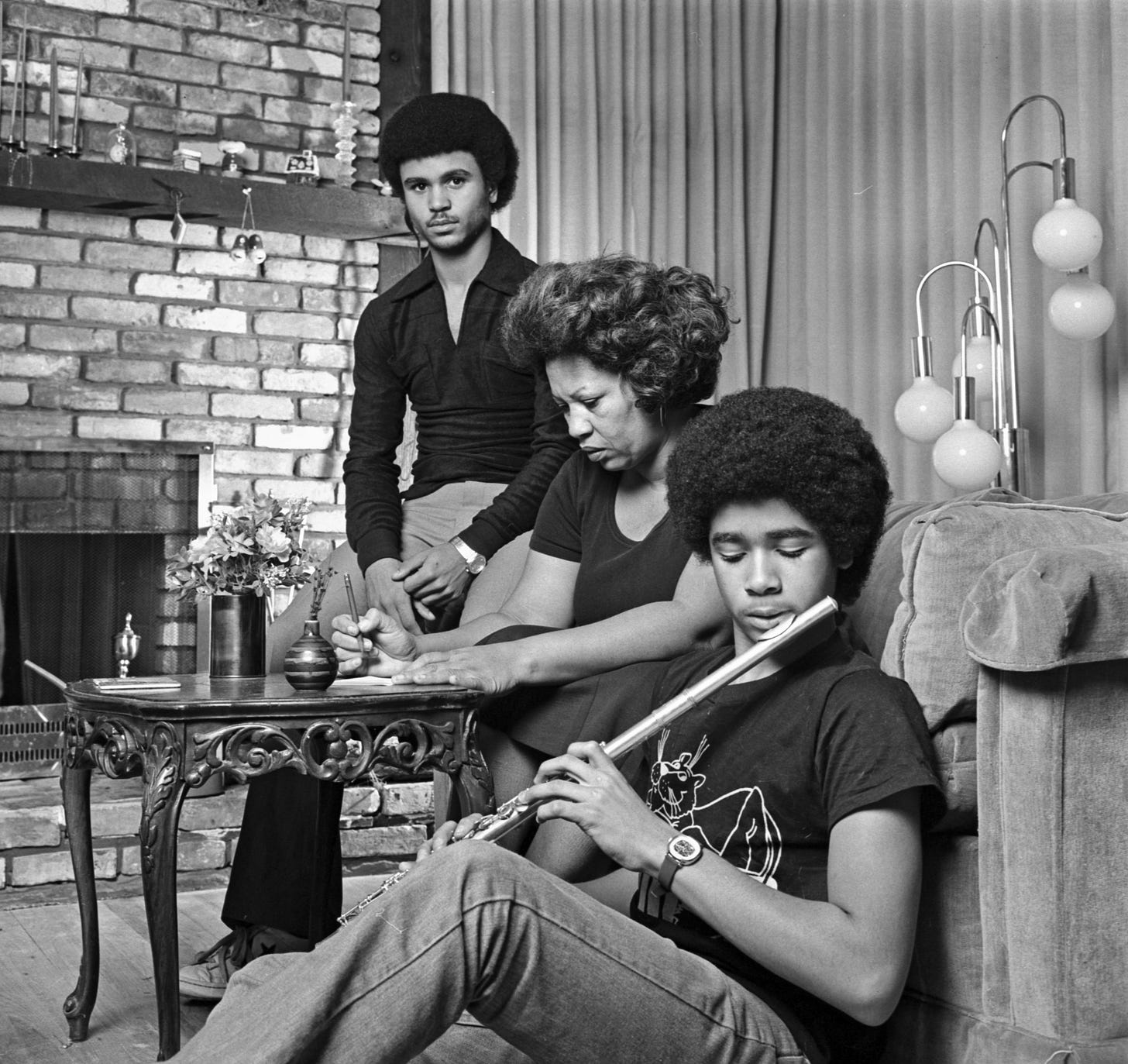

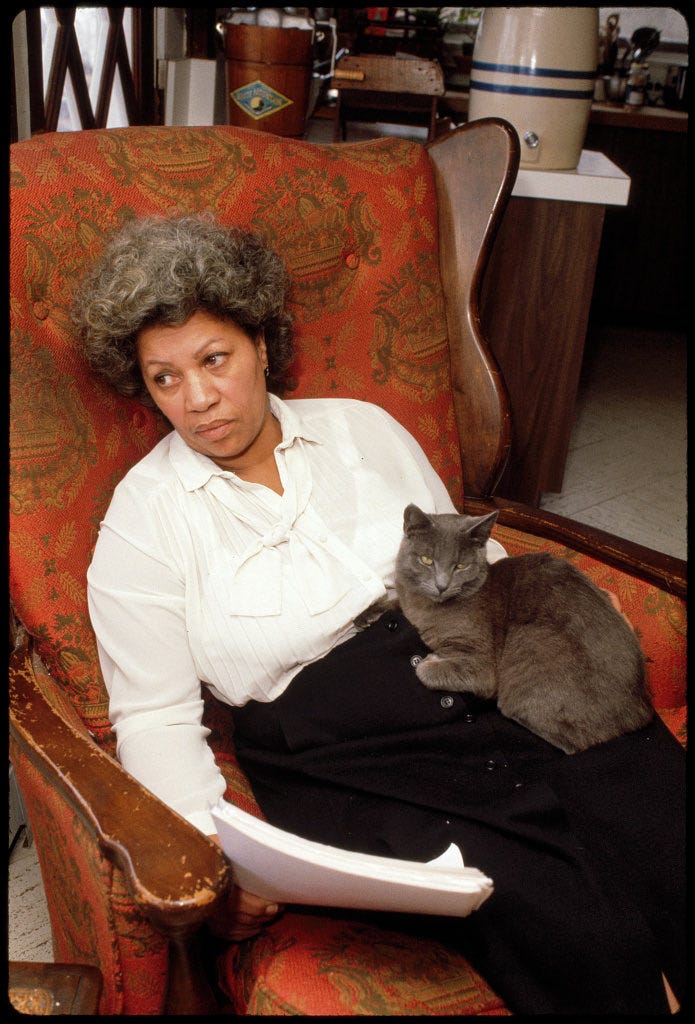

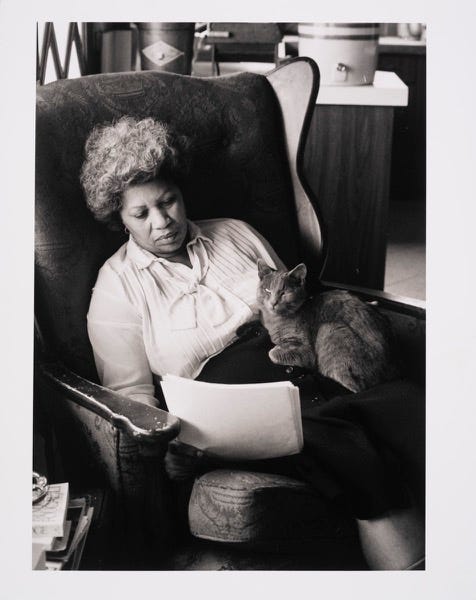

But I like to think that she symbolically brought those relationships with her through her cat, Zora.

While there are very few anecdotes about Zora, there are some photographs of her and Toni, and we know Toni named her after Zora Neale Hurston.

The two writers shared similarities. Toni was the second Black woman to appear on the cover of Newsweek, the first being Zora Neale Hurston. Just like Toni, Zora had moved to Washington D.C. to attend Howard, then headed to New York for graduate school. (Zora Neale Hurston was the first Black woman to graduate from Barnard College.) Zora stayed in New York City, in Harlem, after graduating to cultivate her talents amidst an emergent Black creative movement, similar to Toni.

But Hurston’s work and legacy slid into obscurity for decades after her death—out of print and all but lost to the world. It wasn’t until 1975, at the same time when Toni Morrison was working as an editor at Random House, that Toni’s friend Alice Walker rediscovered Hurston by writing an article about her in Ms. Magazine called "Looking for Zora.”

Toni was clearly paying attention. She read Zora Neale Hurston for the first time after 1977, and Bernard Gotfryd took these photos of her upstate with “Zora” soon after that.

Some have even argued that Toni Morrison’s novel Tar Baby, published in 1981, was “a deliberate rewriting” of Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. Later Hortense J. Spillers wrote, "With Zora Neale Hurston a window is pried open. A breeze blows through, and by the time of Toni Morrison's Beloved, an opening has become a prospect, a landscape of vistas of possibility."12

Despite the similarities in their lives, writing philosophies, and styles, nothing could be more striking than a comparison between Zora Neale Hurston’s legacy and Toni Morrison’s.

Zora died in a Florida welfare home in 1960 and was buried in an unmarked grave. Toni Morrison’s net worth at the time of her death was $20 million and her funeral was attended by 3,000 people, including Oprah Winfrey, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Fran Lebowitz, David Remnick, Angela Davis, and more. Toni Morrison sold millions of books, many through Oprah’s book clubs13, while Zora Neale Hurston’s masterwork, Their Eyes Were Watching God, survived in part through photocopies of the work being passed by Black women writers and academics in English-department hallways and at literature and Black studies conferences.

This difference wasn’t due to mere timing or luck, though those played a part. Where Toni Morrison had Zora Neale Hurston and Black female peers to turn to, Zora Neale Hurston had no lineage, no predecessors, no Sisterhood in her lifetime.

Toni Morrison was able to bring robust mutual support into her own life, and offered it to others once she’d reached success. In addition to teaching throughout her lifetime as well as editing and publishing new voices, in 1994, she founded the Princeton Atelier, a program that invites writers and performing artists to workshop student plays, stories, and music. She and her sons even purchased an apartment building north of her home, up the Hudson, to house artists.

In 1987, upon the publishing of Beloved, Toni was asked what will be lost as she moves away from editing—her role a supporting other writers’ voices—to focus on her own work. Her answer, at 11:40, is beautiful.

I am convinced that the better known I am, the easier it is for other writers to come along.

If I till that soil myself—in publicity, traveling around Europe, selling books, lecturing, what have you—then all of the younger people won’t have to break down those same doors. They’ll be open.

They will write infinitely better than I do. They will write of all sorts of things that no one writer can ever touch. They will be stronger…But part of that availability and accessibility is because six or seven Black women writers, among whom I am one, will already have been there and tilled the soil.

Artists bring many things to our lives—imagination and inspiration, cultural critique, beauty. Great artists can even push us towards more freedom, both personal and societal.

Toni Morrison once said “The function of freedom is to free someone else.” That philosophy wasn’t just transmitted through her stories, but how she and her closest supporters lived their lives—from her peers in The Sisterhood publishing each others’ work and caring for each others’ children, to her parents, born in the south, working overtime to send their precocious daughter to college.

What if more of great artists had aspired towards such generosity and collectivity? How much better would our art be?

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/magazine/the-radical-vision-of-toni-morrison.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/06/books/photos-of-toni-morrison.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1977/09/11/archives/talk-with-toni-morrison.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/27/ghosts-in-the-house

Beloved was published in 1987. It was nominated for the National Book Award, but it did not win. In response, 48 African-American writers and critics—including Maya Angelou, Amiri Baraka, Jayne Cortez, Angela Davis, Ernest J. Gaines, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Rosa Guy, June Jordan, Paule Marshall, Louise Meriwether, Eugene Redmond, Sonia Sanchez, Quincy Troupe, John Edgar Wideman, and John A. Williams—signed a letter of protest that was published in The New York Times Book Review on January 24, 1988. Again, Toni’s community and relationships reveal themselves as key forces in the trajectory of her career.

“Tale" 94

Toni Morrison collaborated with Oprah’s Book Club. When Oprah selected Toni’s first novel The Bluest Eye, for the book club, it sold another 800,000 paperback copies. Oprah would go on to feature three more of her books.

I didn’t know she named her cat after Zora Neale Hurston! But of course she did!

Truly a gift you have delivered here, Thank you for sharing this wonderful story of hard work and inspiration, of giving and growing then giving some more. Such an amazing woman.