Art Dogs is a monthly-ish dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these ~monthly posts to your email inbox.

“In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland.”1

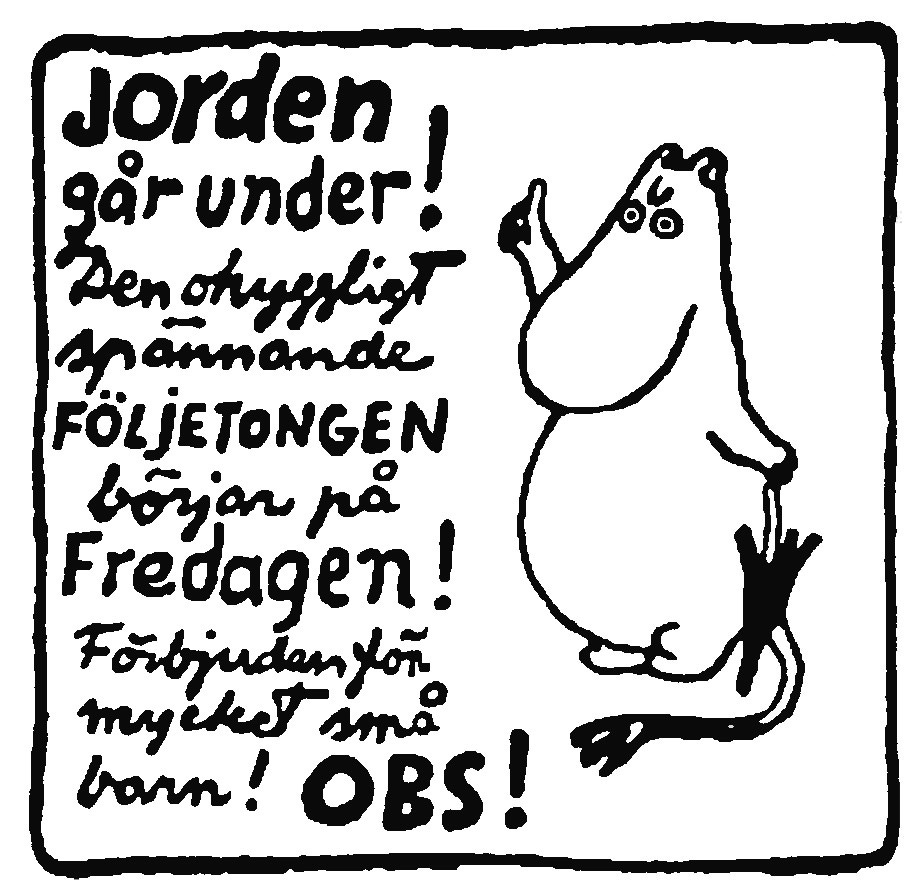

That lesbian artist was Tove Jansson, creator of the Moomins. At its peak, her Moomin comics was reaching an astounding 20 million readers in a single day.

Today, the Moomins is the most popular Finnish series of all time, and Tove is a national icon. The series has been adapted for screen, for stage, and even as an opera. During Tove’s career she received more than 50 honorary awards and nominations, including the Hans Christian Andersen medal in 1966. Tove has a park named after her in Helsinki, stamps made in her honor, and there are Moomin amusement parks in Finland and Japan. (If you are American and don’t know the Moomins well, it might be because Tove turned down Walt Disney’s offer to buy exclusive rights to the characters, opting instead to retain ownership in full in a family company. That business, which is now run by Tove’s niece, Sophia, holds the artistic control over her legacy. It brings in over $850 million each year.2)

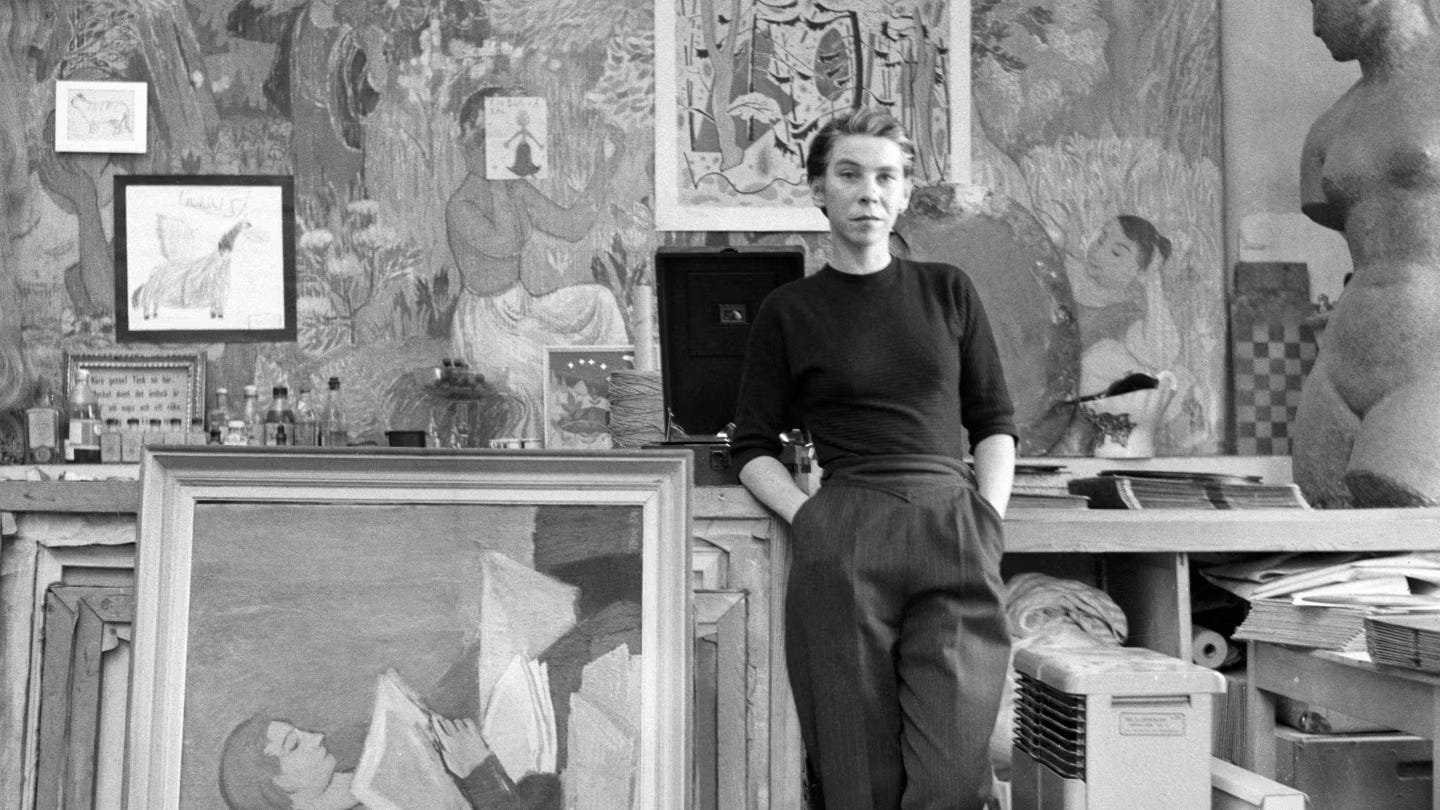

Despite the fame and fortune the Moomins brought her, Tove never lost her grounding. In addition to writing the series, she pursued painting primarily as an artist her entire life and wrote eight novels and four picture books.

To sustain such an ambitious creative focus, she balanced building a rich community of friends and family with taking deliberate remove from a world that had so many demands of her.

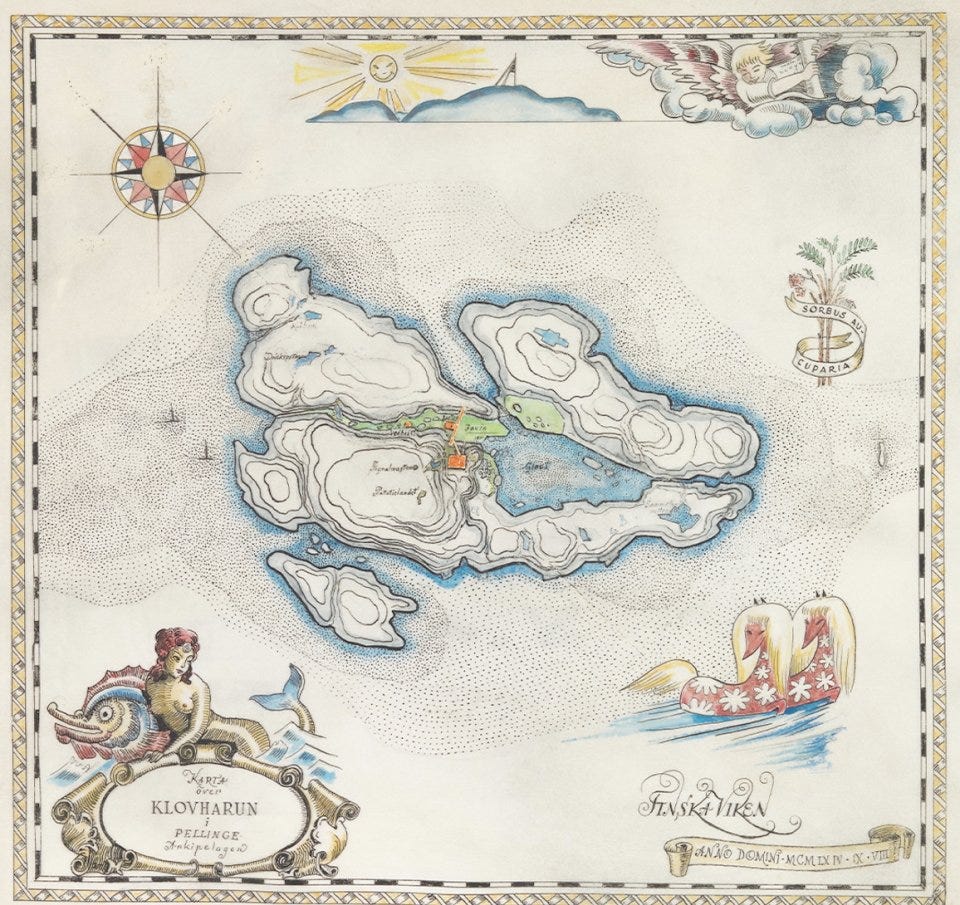

Most notably, she spent close to 30 of the final summers of her life alone with her partner, Tooti, and their cat on Klovharun, a rocky and inhospitable island in the outermost archipelago of the Gulf of Finland, close to islands she had visited regularly as a little girl.

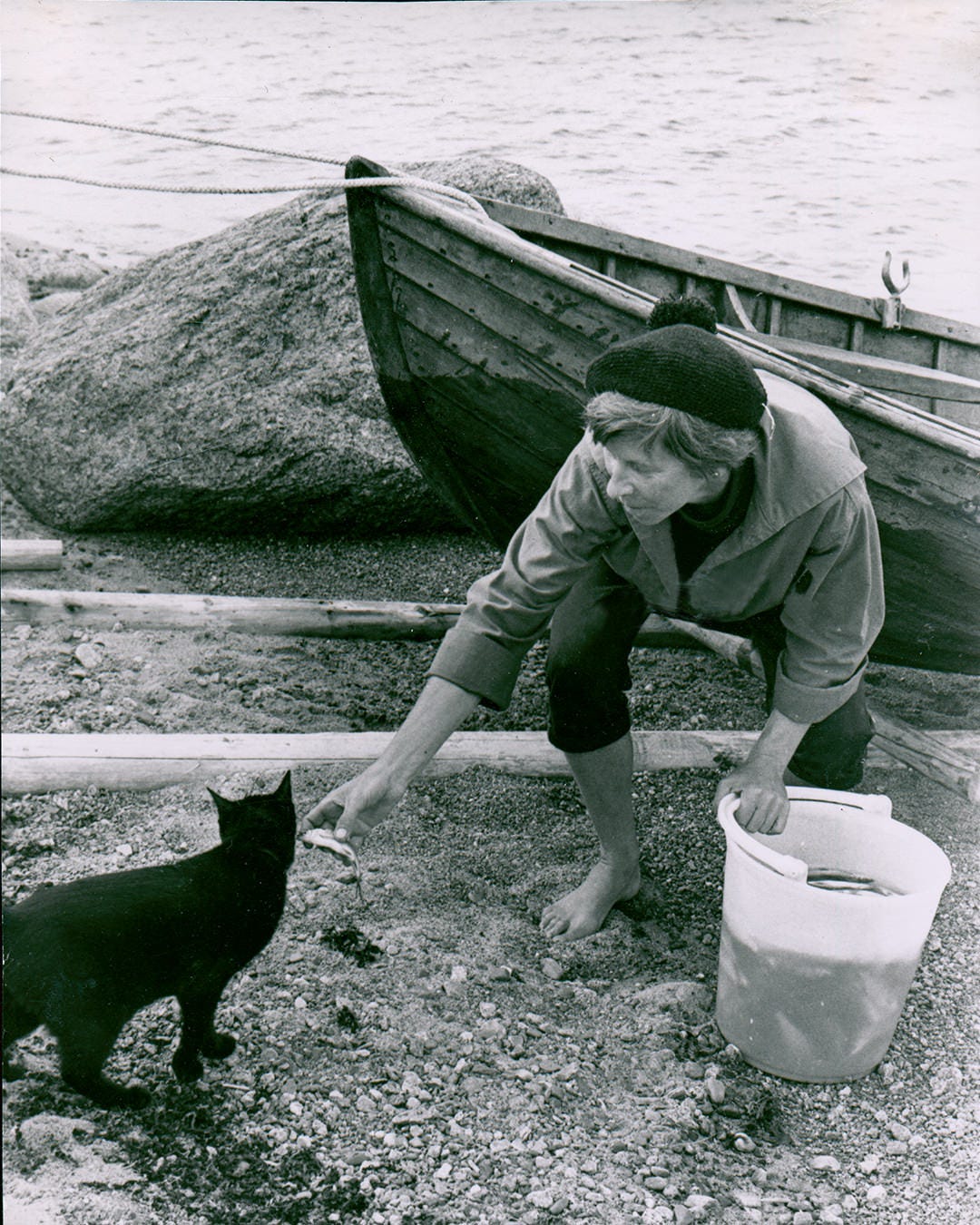

The couple slept in a tent on Klovharun, caught their own fish, made art, and danced. (Tove loved dancing; Tooti loved filming her.) Occasionally, fisherman or family moored for a visit, but most days they were alone with the sea, the landscape, their art, and each other.

Tove Jansson was born in Helsinki, Finland, in 1914, to a sculptor father and an illustrator mother. Finland was part of the Russian empire then, and in her lifetime Tove would bear witness to the country’s separation from the Russians, two world wars, and a Finnish civil war.

Tove’s life philosophy and the work she created for the world are the rare artistic artifacts of a happy childhood. Despite the strife and suffering occurring in the world around them, Tove’s childhood home offered a loving creative cocoon. As both of Tove’s parents were well-respected artists, they encouraged their children creatively. “Home and studio were one,” wrote Boel Westin in her biography, “with no clear distinction between work and family life.” The siblings came to see that working as a professional artist was “the obvious way to spend each day, and the meaning of existence.”3

All of the Jansson children would become artists, with Tove publishing her first story at just 14 years old. Having the childhood home full of art and artists who were “facing the compromises of daily life” had a significant impact on Tove’s philosophy as an artist. She would put her painting and freedom first—before fame, fortune, or stability—until her final days.

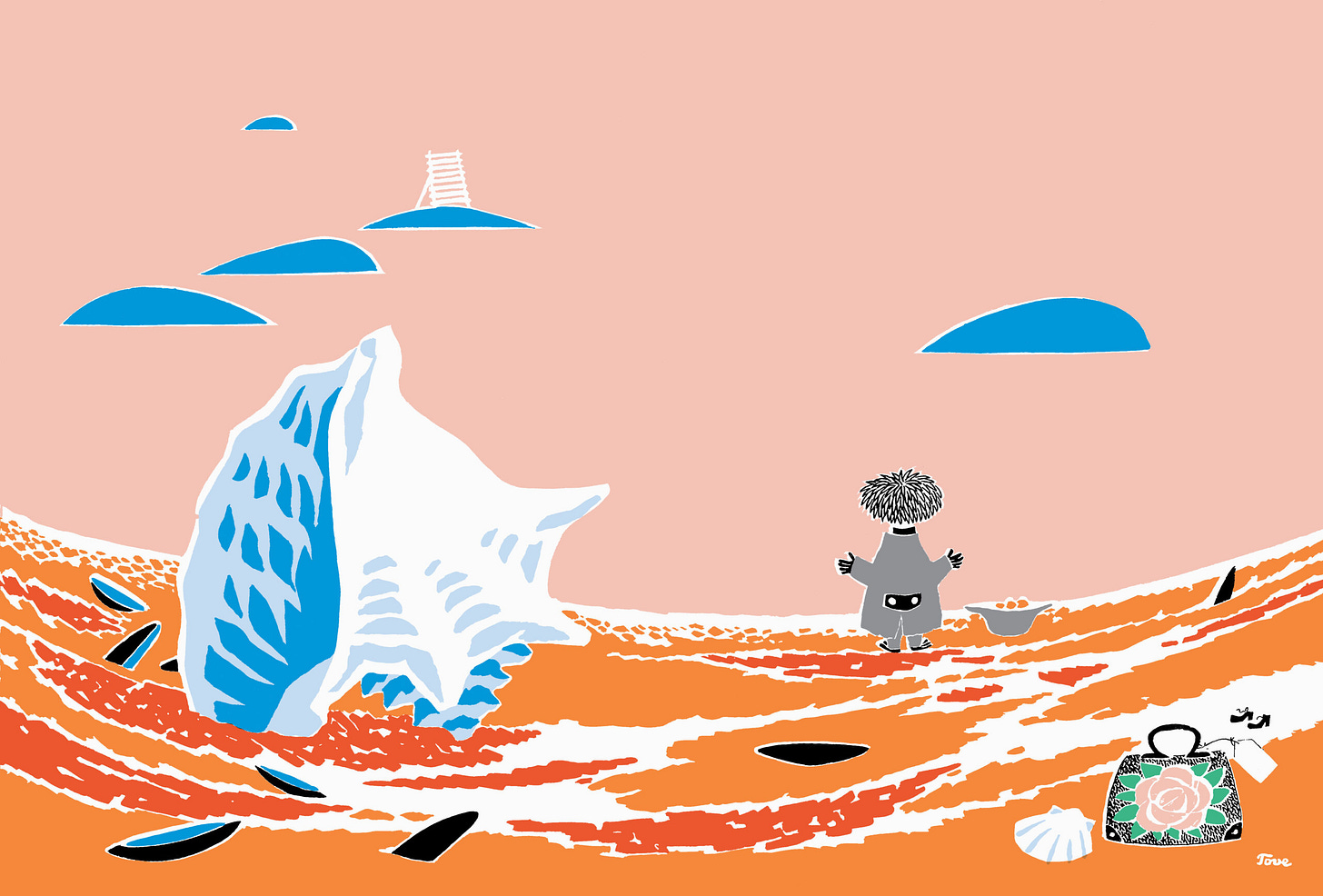

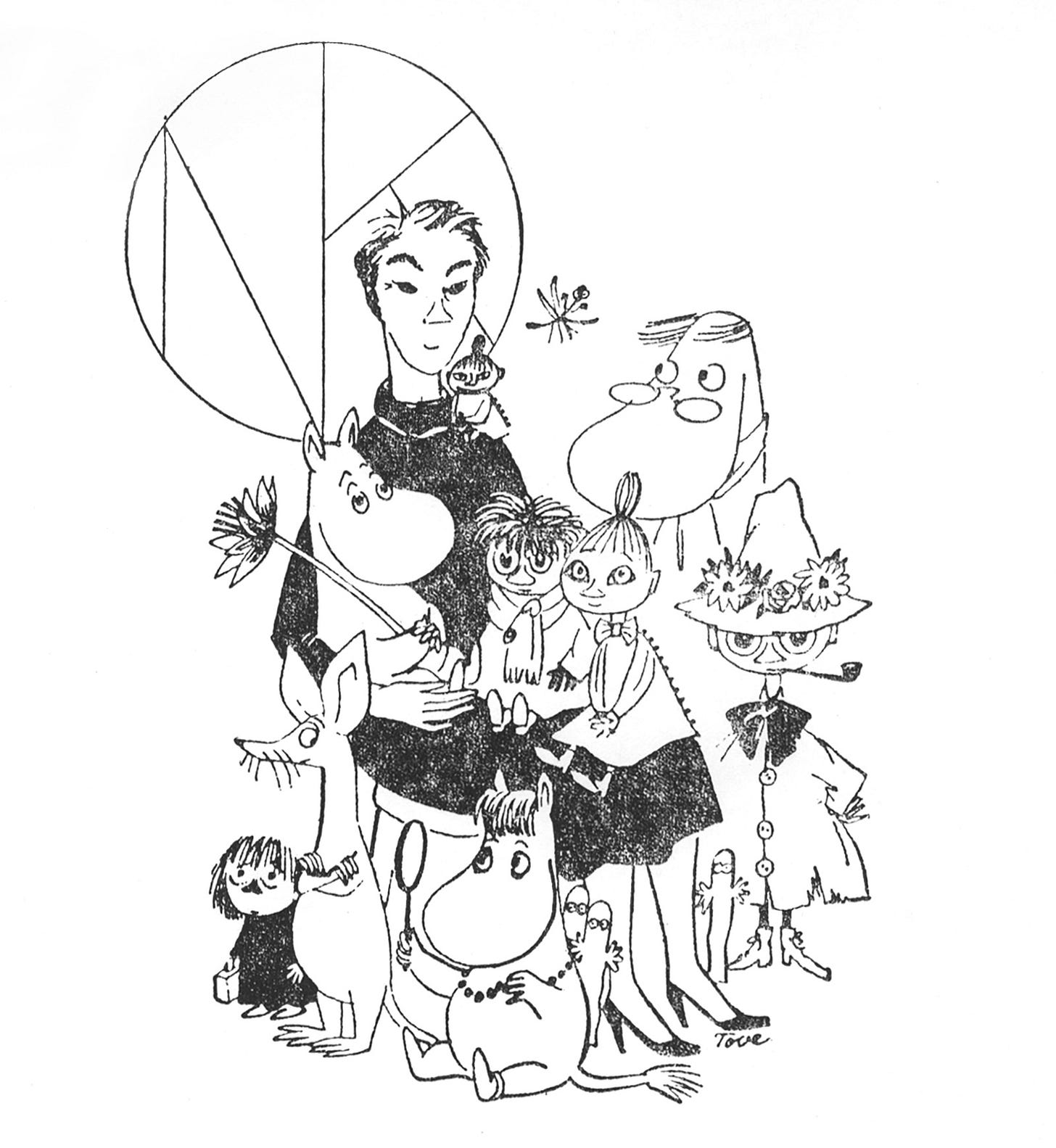

During World War II, Tove started producing cartoons for magazines and newspapers to earn money and support her career as a painter. She created the Moomins in this moment of war and poverty, a time when children’s stories were rare. She later wrote to a friend that the Moomin characters had taken shape “when I was feeling depressed and scared of the bombing and wanted to get away from my gloomy thoughts to something else entirely. . . . I crept into an unbelievable world where everything was natural and benign—and possible.”4

Tove’s parents, siblings, friends and lovers directly inspired the Moomin characters. As Sheila Heti writes for The New Yorker:

Jansson built her narratives around an idealized notion of home: her creatures ventured out on their own, but some sense of safety followed them everywhere, an assurance of a familial love that left them to enjoy their solitude, rather than fear it.

The Moomins “trusted and supported each other in every way” and acted as a creative team. Much like in Tove’s young life, “community and the power of art” are what see Moomin through challenges time and time again.5

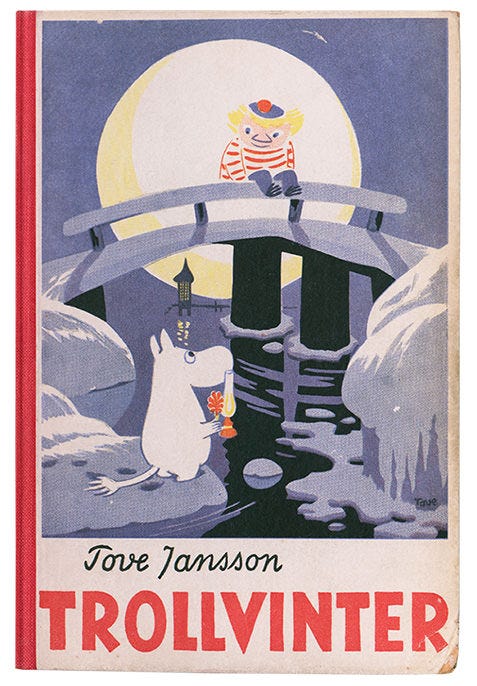

At first, Tove kept her drawings secret—she saw them as an unserious personal project. But in the final months of World War II, at a friend’s urging, Tove published The Moomins and the Great Flood. Readers met a young Moomintroll, the Moominmamma, and Sniff as they searched through forest and flood for a lost Moominpappa.

The Moomins were an immediate hit. Within a decade, the comic strip was being published weekly in over a hundred newspapers around the globe, including England’s Evening Standard, the most widely distributed paper in the world. There was eventually a Moomin television show in Sweden, an anime series in Japan, and “a deluge of merchandise: ‘trinkets and marzipan and candles,’ cups and dishes, even menstrual pads.” Having previously lived on meager income, the regular compensation offered a “huge relief” to Tove.

Another major change arrived for Tove as the war was coming to a close. Throughout her 20s, she’d had love affairs with men—three of whom proposed marriage to her, all of which she declined. In 1946, she fell in love with a woman for the first time. Same-sex relationships were illegal in Finland until 1971, but Tove would privately share with close friends the she had gone over “to the ghost side” (ghost was both a slang word for lesbian and an allusion to the discretion required of them). She wrote the following about how it felt to fall in love with a woman for the first time:

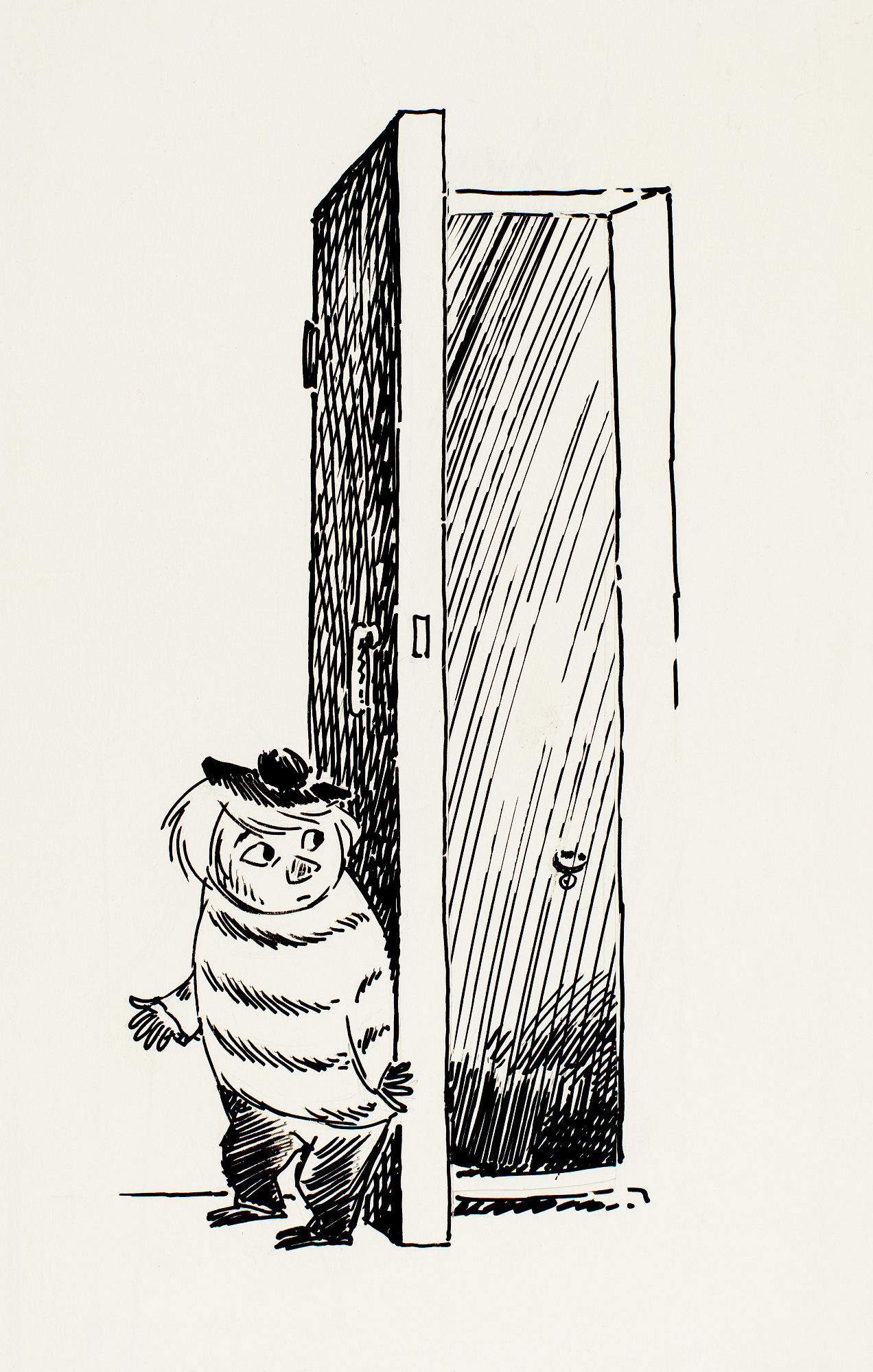

It came as such a huge surprise. Like finding a new and wondrous room in an old house one thought one knew from top to bottom. Just stepping straight in, and not being able to fathom how one had never known it existed. . . . I’m finally experiencing myself as a woman where love is concerned, it’s bringing me peace and ecstasy for the first time.

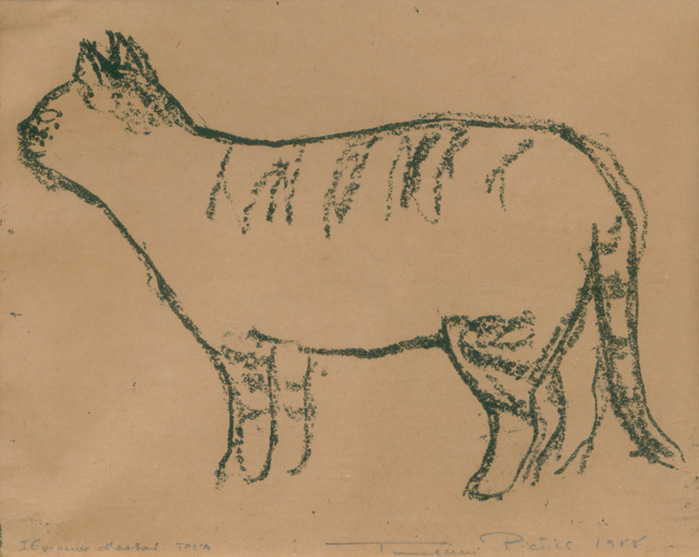

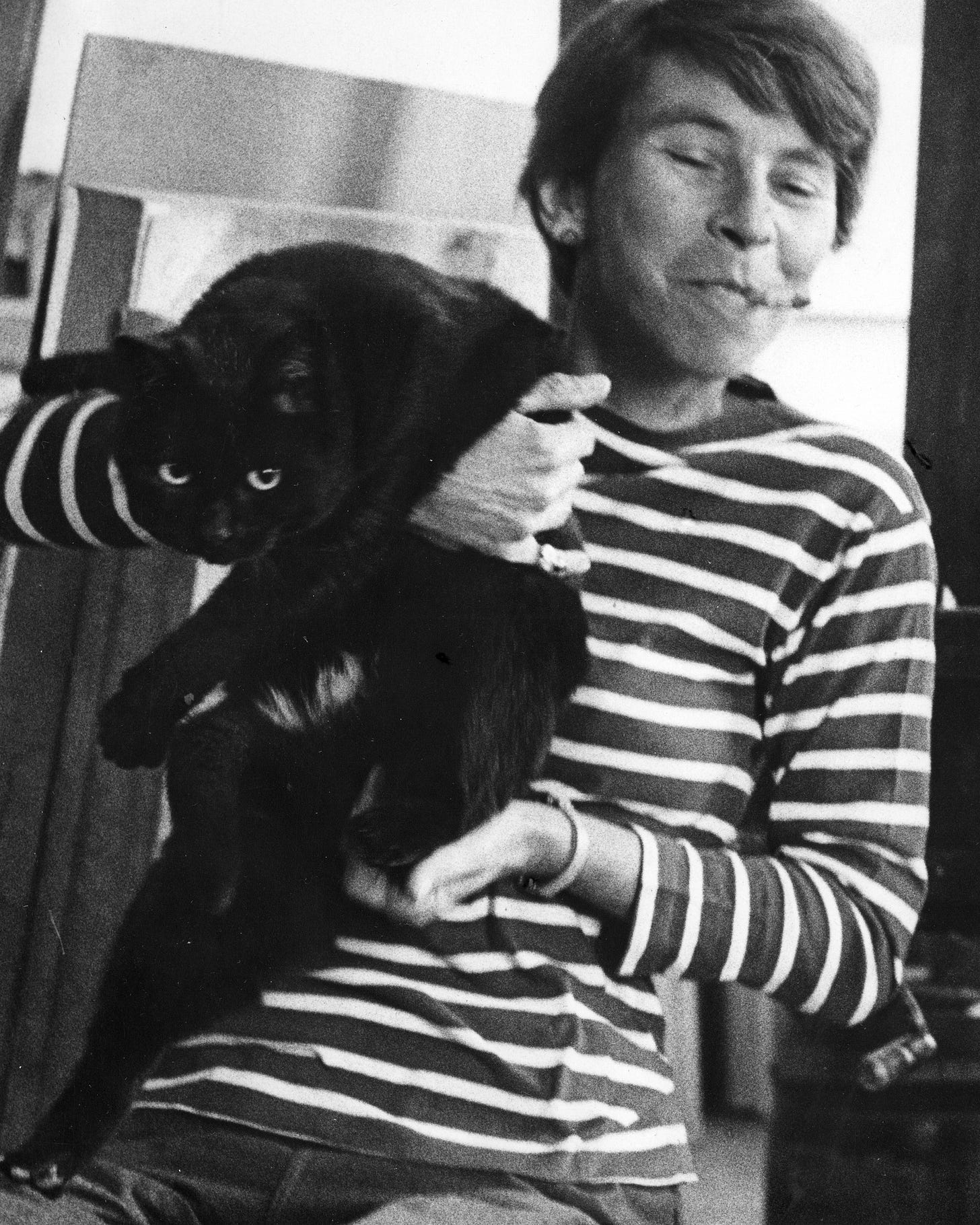

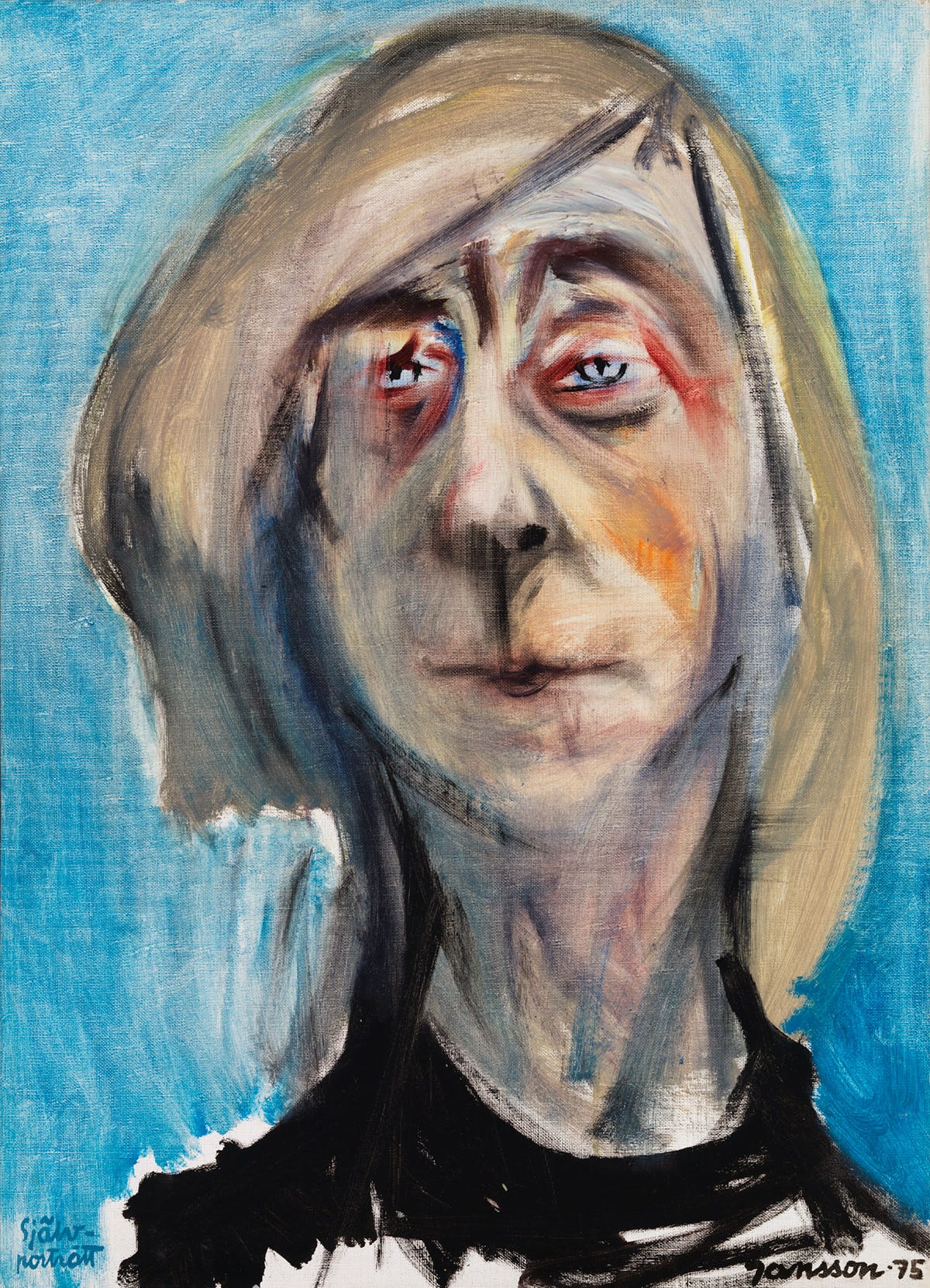

At a Christmas party in 1955, as the Moomins were reaching tremendous global fame, Tove met the artist Tuulikki (“Tooti”) Pietilä. They connected taking turns choosing records to play, and Tove asked Tooti to dance. Tooti refused, unwilling to break with social convention, but immediately after the party mailed a Christmas card depicting a striped cat to Tove’s studio. Soon Tooti would move into the studio next door. “At last I’ve found my way to the one I want to be with,” Tove Jansson wrote in one of her first letters to Tooti in June 1956.6 Tove was 42, and she stayed with Tooti until the end of her life.

By 1959, running the Moomin empire was taking its toll on Tove. Fame—parties, appearances, interviews—and the weekly comic strip consumed too much of her time, time she’d rather spend painting. Tove decided to transfer production of the weekly comics to her brother Lars and terminate her own contract prematurely.

With newfound time, Tove and Tooti began to travel for pleasure, an activity they continued to do actively for the remainder of their lives, often without too much planning. (“They didn’t usually book hotels in advance.”)

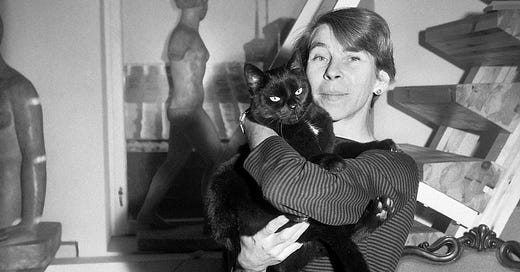

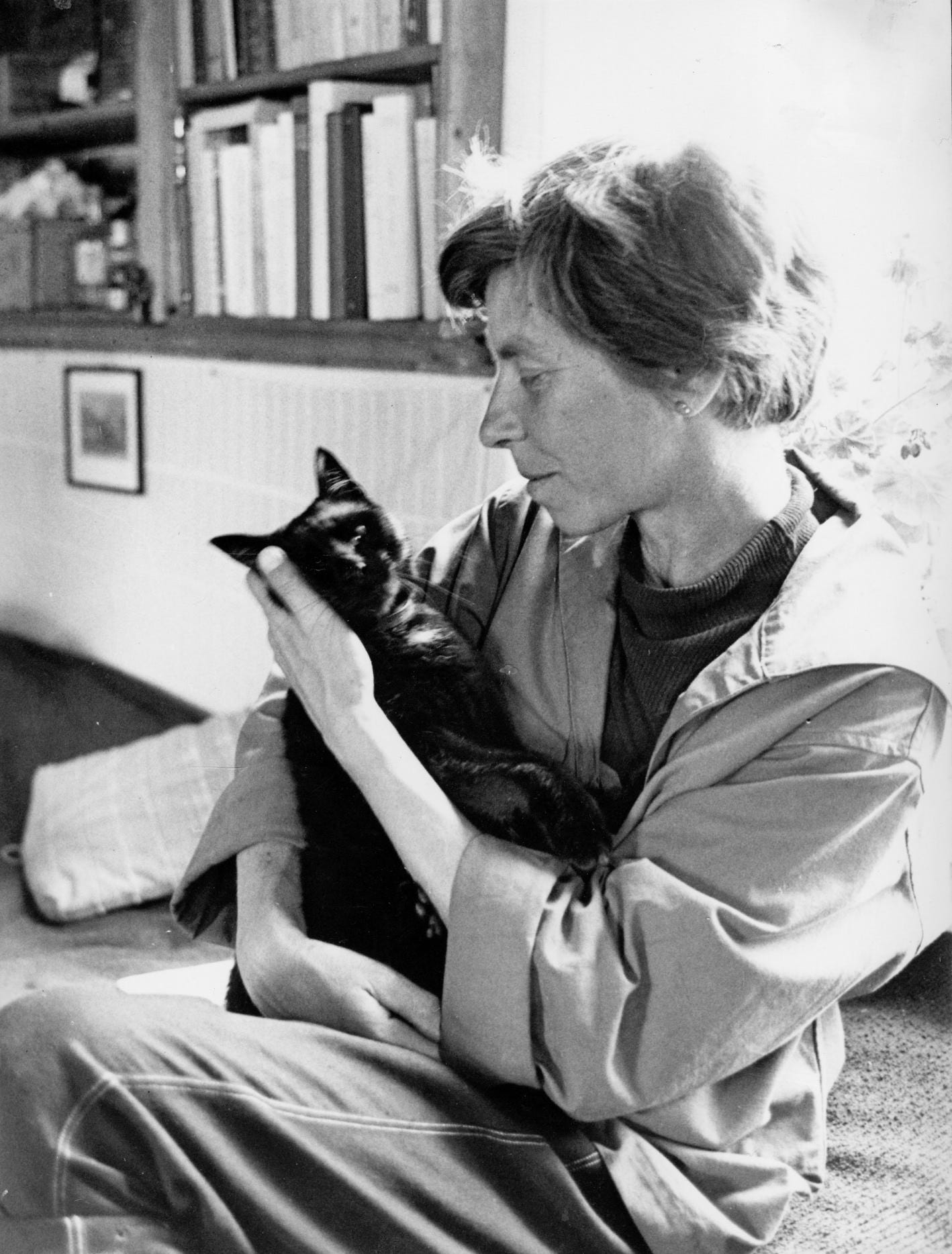

Their first trip took them to Greece in 1959, and by the early 1960s a black cat had appeared in their lives named Psipsina (Greek for “pussycat”). It’s rumored that Tove’s mother was the one who raised the cat and then passed her to Tove. Tooti would capture Psipsina in a number of her drawings.

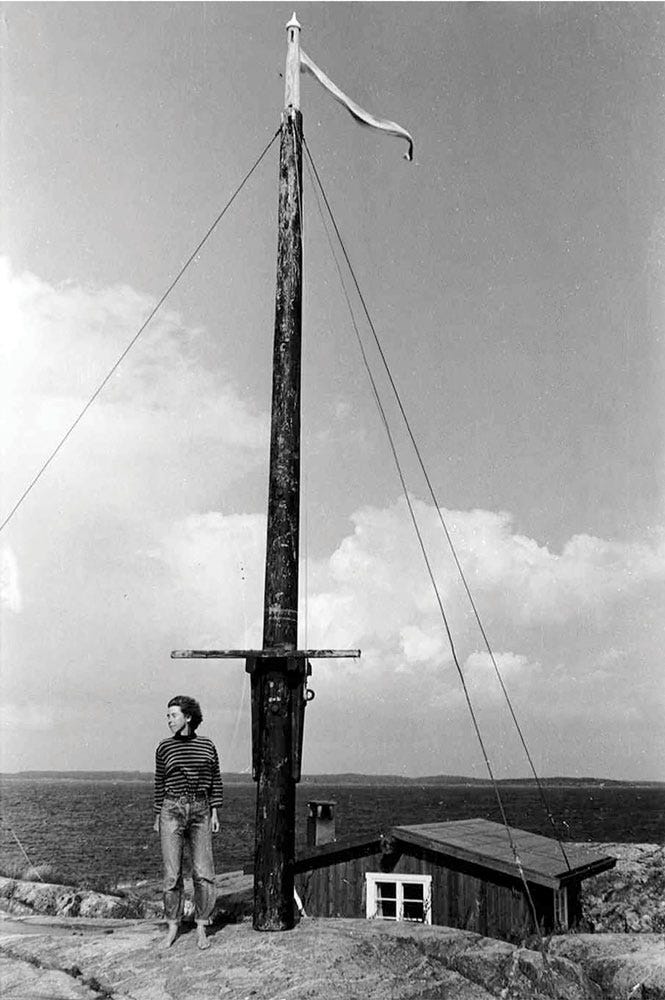

The couple also sought out solitude “to avoid the bombardments of the world—to find someplace where the performance could end.” In 1964, the year Tove turned 50, she and Tooti bought their own small island: Klovharun.

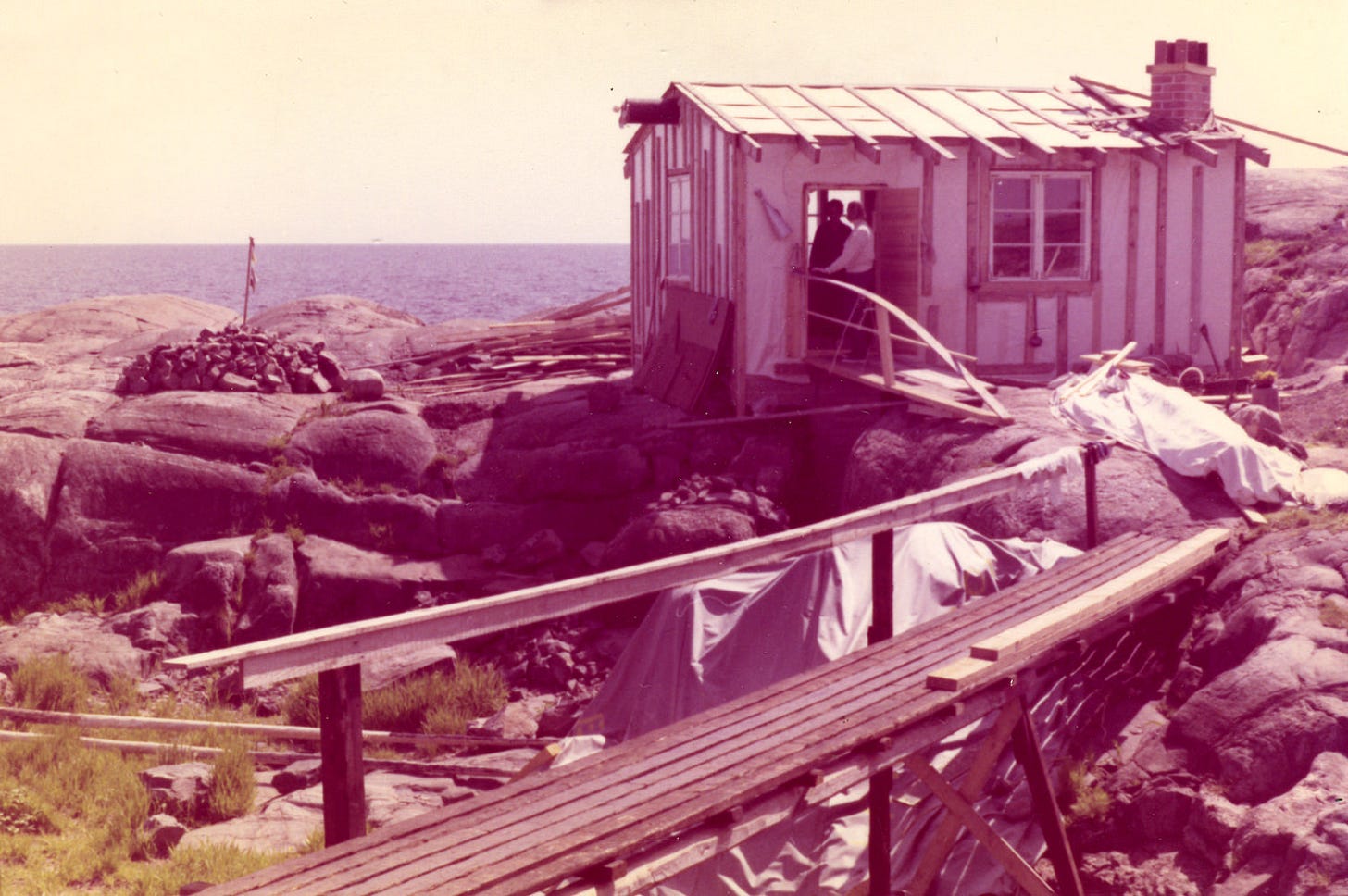

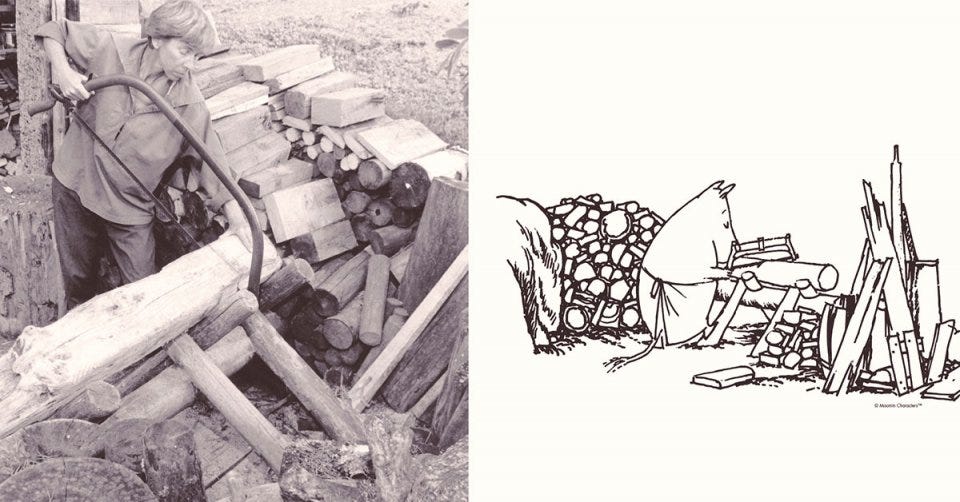

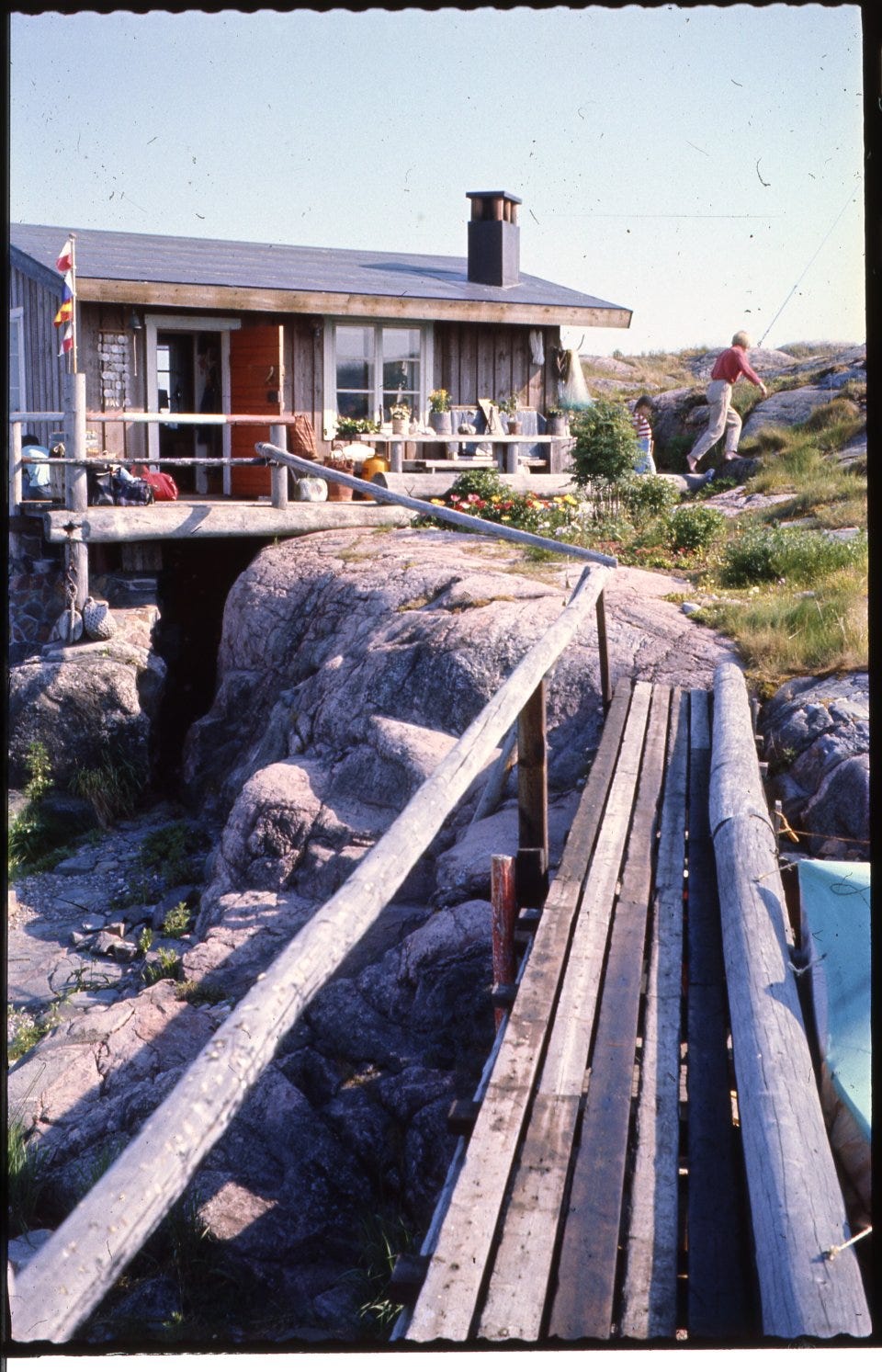

On Klovharun, the couple slept in a tent with Psipsina, listening to crashing waves as strong gusts blasted their tent walls. A fisherman helped them construct a simple one-room fisherman’s cabin. (Even when the cabin was ready, Tove and Tooti still chose to sleep in the tent, offering the cabin to guests.) The women chopped wood, caught their own fish, and rowed their mahogany boat to land for more supplies when needed. Otherwise, they were free to explore nature and make art. “They weren’t very young when they moved out there, they were almost 50. Many people raised their eyebrows to the idea of building a house on this deserted island in the outer archipelago,” Sophia Jansson, Tove’s niece, recalled. “There was no electricity or running water on the island and it was difficult to get there. Since they were women, people thought they would never make it. But they proved them all wrong.”

Sheila Heti captured what this reclaimed lifestyle meant for Tove and Tooti beautifully in The New Yorker:

On her islands, Jansson’s many contrary aspects—the self that valued solitude and the self that valued friendship; the self that loved adventure and the self that loved routine—were easily made one. In a letter, Jansson describes waking up early with Pietilä, “always simultaneously though we sleep in separate beds.” They lie together in the mornings and listen to the radio; Jansson lets out the cat, makes coffee, reads novels. Later, she walks along the beach and brings in the wood:

We rarely clean the house and only have the occasional wash, with much brouhaha and pans of hot water on the ground outside. Then we do our own private thing until dinner, which we eat sometime in the middle of the day, our noses in our books. We get on with our work. . . . We don’t talk much. And so the days pass in blessed tranquility.

Even in the city, the couple preserved a distance within their intimacy; they kept separate apartments, joined by an attic corridor through which they visited each other every day.

…

Much of Jansson’s later fiction expands this idea of contentment. Love, for her, is premised on a delicate balance between the reliable presence of another person and the freedom to inhabit one’s private universe…In “Fair Play,” a novel that is loosely based on Jansson and Pietilä’s relationship, Mari, a writer, and Jonna, an artist, live and work in side-by-side studios. Jonna receives an award that will take her to Paris, to a studio “meant for her use alone.” Worried about leaving Mari behind, she is unsure whether to accept. She nervously justifies herself, explaining “the importance of illustration, the painstaking labor, the concentration” needed to do one’s best work. But Mari finds herself unafraid of the prospect:

A daring thought was taking shape in her mind. She began to anticipate a solitude of her own, peaceful and full of possibility. She felt something close to exhilaration, of a kind that people can permit themselves when they are blessed with love.

In the 1970s, Tooti bought a Super 8 camera and began recording both their travels and their life on Klovharun. You can see more old videos of Tove and Tooti on Klovharun here and here.

Tove on Klovharun in 1982

Tove packing up their boat to leave Klovharun in 1983

Tove after her 75th birthday party in 1989, the year she published Fair Play, a novel about two older women and the life they've built together.

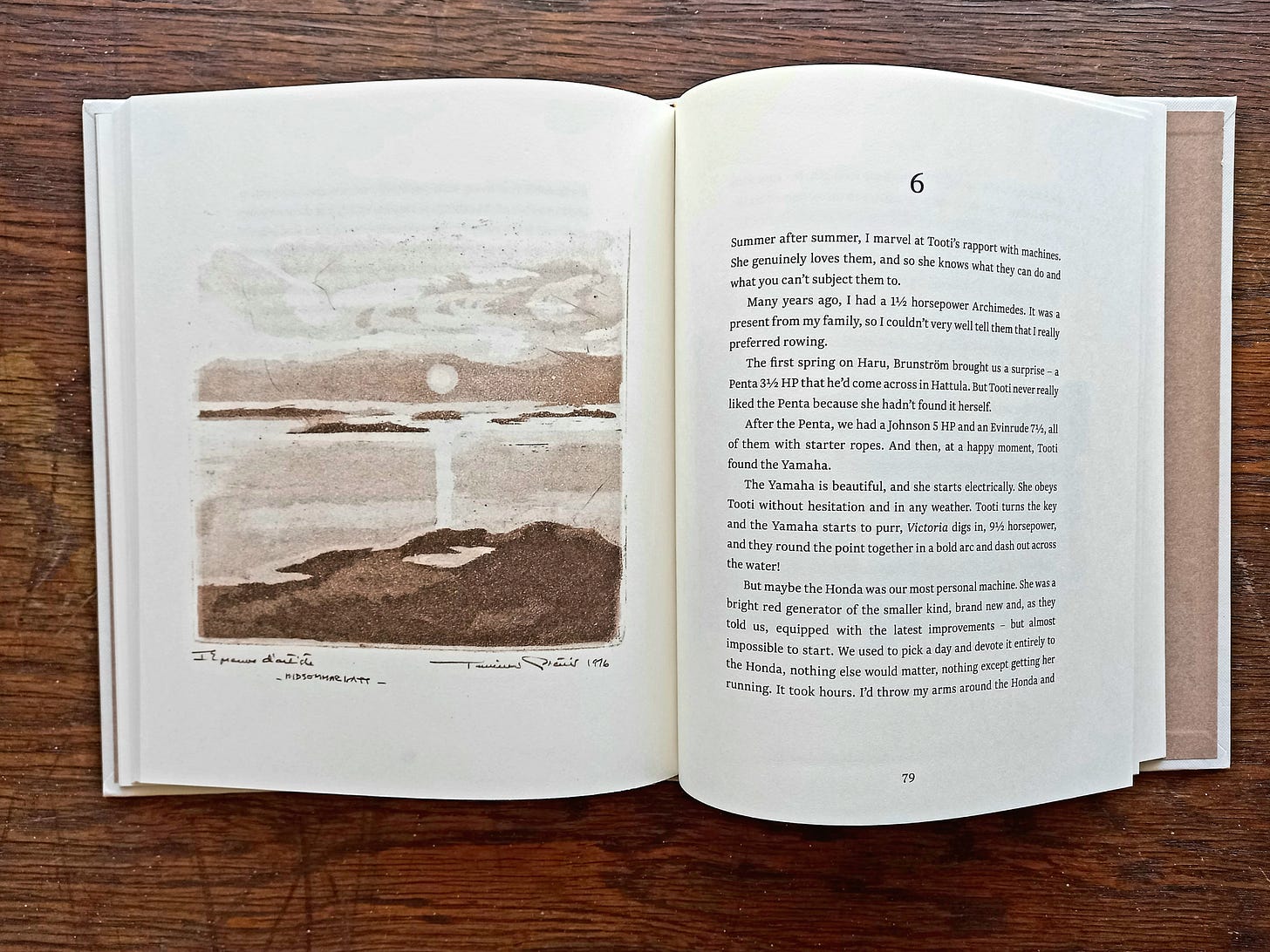

The pair returned annually to Klovharun until they were well into their 70s and it was no longer safe. Tove wrote in a beautiful book that her and Tooti created together about their island:

“And last summer, something unforgivable happened: I started to fear the sea. The giant waves no longer signified adventure, but fear, fear and worry for the boat and all the other boats that were sailing in bad weather. [...] We knew that it was time to give the cottage away.” — Anteckningar från en ö (Notes From an Island), 1996

On September 30, 1991, their final night in Klovharun, Tove signed a deed gifting the cabin to the Pellinge District Resident’s Association, which rents the cottage as an artists’ residence and also organizes open days and guided tours.7 The couple never returned to Klovharun, not even for a visit.8

At the end of her life, Tove became seriously ill from breast and lung cancer. During this time she lived in Tooti’s studio, which was in the same building as her own studio but had a separate entrance and a private passage, so the two could move secretly between them.

When the Finnish government awarded her an honorary professorship at the age of 80, Tove remarked:

I've had an exciting, varied life that I am glad of, though it has been trying as well. If I could live it all over again, I'd do it completely differently. But I won't say how.

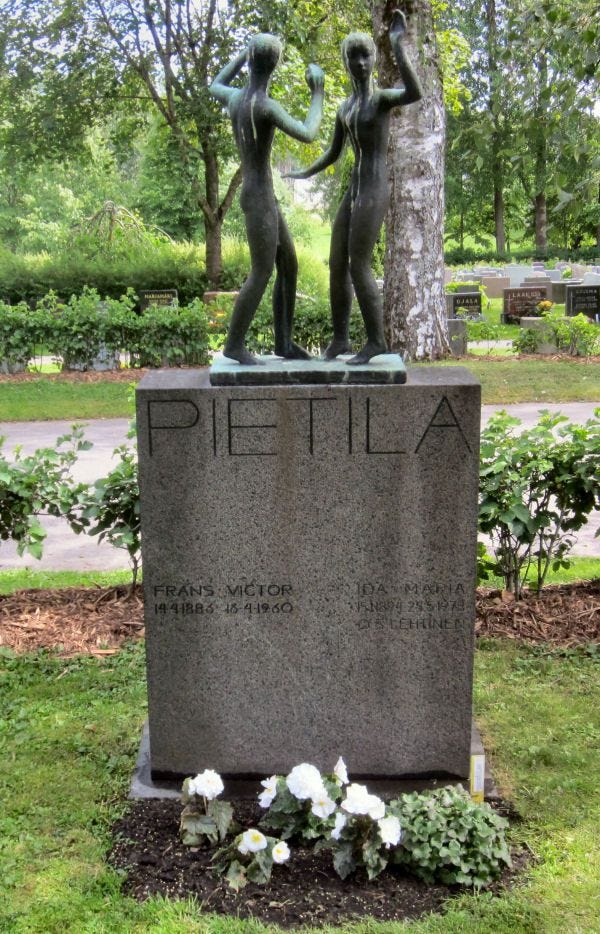

Tove Jansson died on June 27, 2001. She is buried with her parents and brother Lars in Sandudd Cemetery in Helsinki. The major obituaries made no mention of her and Tooti’s life together.

Tooti died eight years later. She was buried in a different cemetery, but is perhaps not so separate from Tove after all. In the end, it seems she honored Tove’s request for a dance.

Rest in peace, Tove and Tooti.

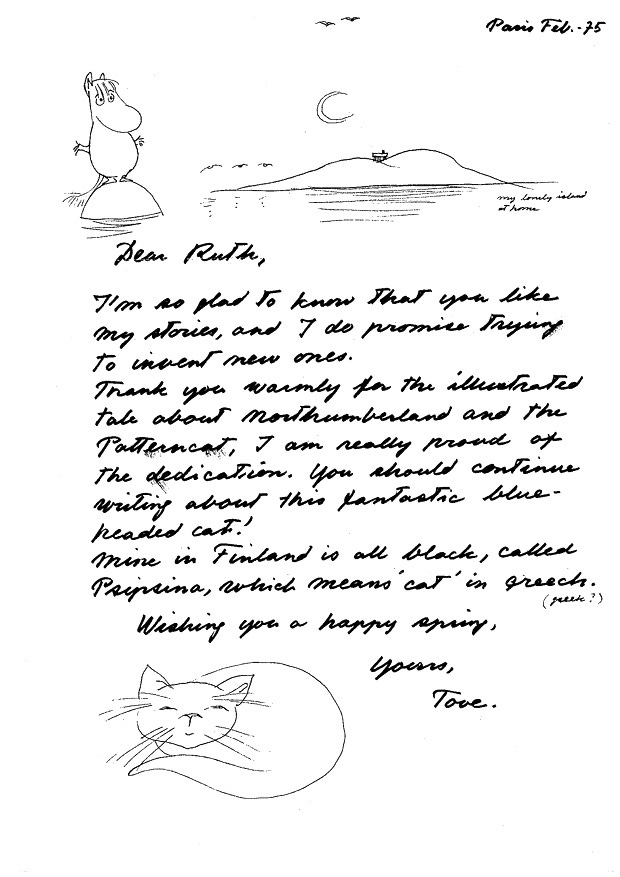

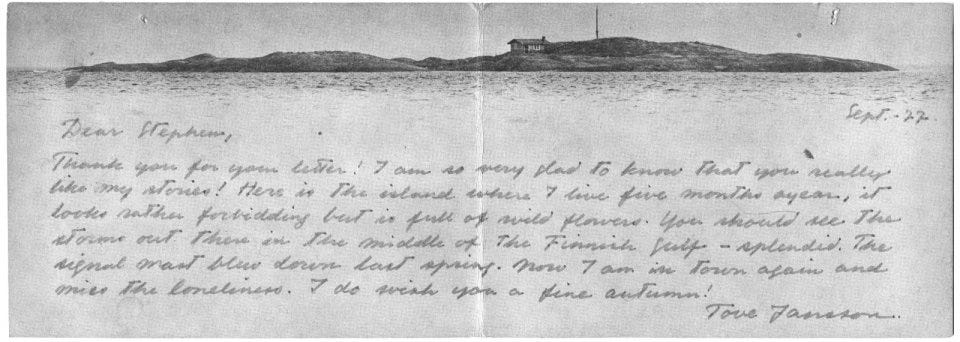

Bonus 1: Fan Mail

When Tove and Tooti would row to the closest town from Klovharn, they would collect their mail and Tove would often spend the entire day responding to correspondence and letters from admirers.

She received an average of 2,000 letters a year and answered each one of the personally, always by hand, and often with special drawings included.

Bonus 2: A cat dressed as Tove

Art Dogs is a monthly-ish dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these ~monthly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/inside-tove-janssons-private-universe#:~:text=In%20the%20nineteen%2Dfifties%20and,by%20children%2C%20celebrated%20by%20adults.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/arts/finland-moomins-lapinlahti.html#:~:text=Alamy-,Ms.,euros%2C%20or%20about%20%24850%20million.

https://tovejansson.com/story/tove-jansson-family-studio/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/inside-tove-janssons-private-universe#:~:text=In%20the%20nineteen%2Dfifties%20and,by%20children%2C%20celebrated%20by%20adults.

https://tovejansson.com/story/moomin-history/

https://tovejansson.com/people/tuulikki-pietila/

https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/tove-jansson-creator-of-the-moomins/

https://www.finnishdesignshop.com/design-stories/travel/on-klovharu-island-tove-janssons-spirit-and-handprint-live-on?srsltid=AfmBOop4P0MEbi0lHUFsDHy1XC72_30ZRFy5qutc2pURYW1K7fN6J4px

This was an absolute delight to read. Thank you.

I loved learning about this person I’d never known about. What an interesting life! Thanks for writing and sharing.