Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Willie Howard Mays, or "the Say Hey Kid," is one of the greatest baseball players to ever step foot on the field. He ranks second behind only Babe Ruth on most all-time lists.

He also seems to have been a pretty stand up guy. Here are some of the things people said about Willie Mays in his prime. I’ve never seen praise quite like it—so wide-ranging and enthusiastic:

“I’m not sure what the hell charisma is, but I get the feeling it’s Willie Mays.” — Ted Kluszewski

"The best Major League ballplayer I ever saw was Willie Mays. Ruth beat you with the bat. Ted Williams beat you with the bat. Joe DiMaggio beat you with the bat, his glove and his arm. But Willie Mays could beat you with the bat, with power, his glove, his arm and with the running. He could beat you any way that's possible." — Buck O'Neil

“They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays.” — Ted Williams

"He would routinely do things you never saw anyone else do. He'd score from first base on a single. He'd take two bases on a pop-up. He'd throw somebody out at the plate on one bounce. And the bigger the game, the better he played." — Peter Mogawan

“Willie Mays, to me, was the best ballplayer I ever saw in my life. …Nobody in the history of baseball is going to see anyone like Willie Mays. Everybody loved Willie in the clubhouse. Willie used to do a lot of things for different players, especially the rookies. Willie used to take players to clothing stores to buy them clothes. Sometimes he would get free clothes, shoes, and stuff, and give them to the players. He was like the mother of the team.” — Juan Marichal

“There have been only two geniuses in the world: Willie Mays and Willie Shakespeare.” — Tallulah Bankhead

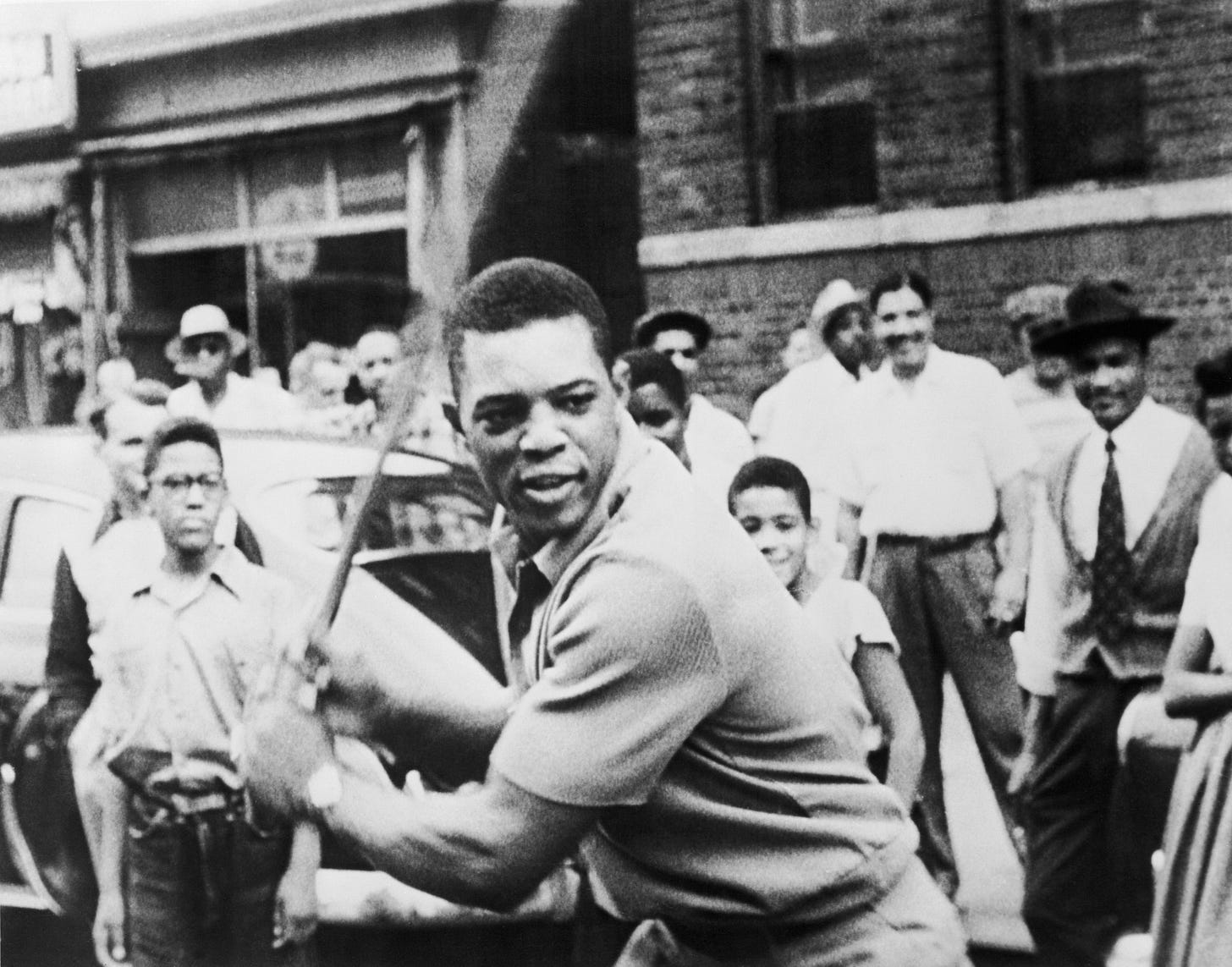

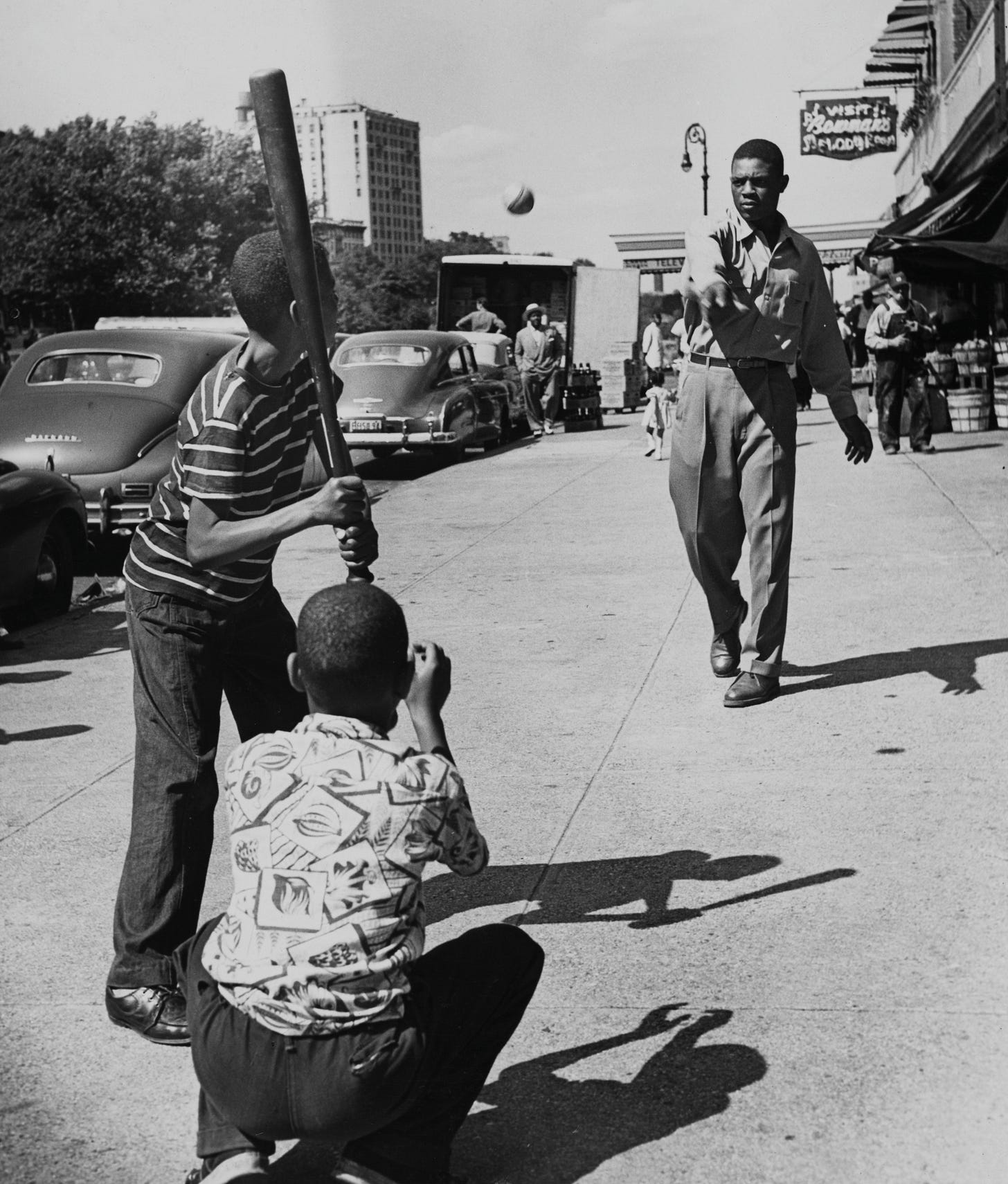

Even in the height of his career, he was known to regularly play stickball in Harlem with kids. He would reportedly play two to three nights a week during homestands until his first marriage in 1956. (You can watch footage of Willie playing in Harlem in 1950 here.)

Among his many accolades, Willie Mays may have made the most famous play in the history of the sport, known as “The Catch” in 1954 during the World Series. Of the play, Willie Stargell said: “I couldn’t believe Mays could throw that far. I figured there had to be a relay. Then I found out there wasn’t. He’s too good for this world.” He would go on to win that 1954 World Series, then four more over the course of his career.

Willie Mays was born in Westfield, Alabama, in 1931. Growing up, he was a star athlete—the best high school quarterback and point guard in the county. At the time, baseball was the only opportunity for black athletes to earn a living in professional sports and the alternatives were slim. Willie’s high school was training him for a career as a dry cleaner.

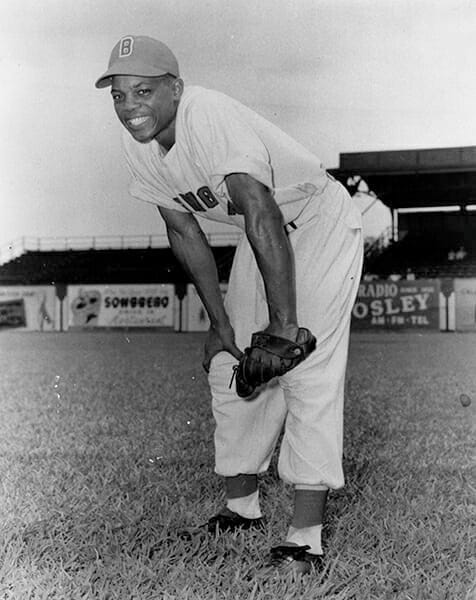

Willie’s professional baseball career started before he graduated from high school. In 1947-48, he played with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, a Negro minor league team, and the famed Birmingham Black Barons.

Willie was called up by the New York Giants in 1951, then served in the Korean War for three years, returning to baseball in 1954. That year he made “The Catch,” won his first World Series, and was named the MVP of Major League Baseball.

Following the 1957 season, the Giants relocated to San Francisco. By then, Willie Mays was world famous, and was soon to be the highest paid player in baseball. During this time, in the prime of his career, Willie watched from afar as Birmingham turned into a racial battlefield.

Despite his talent and fame, when Willie arrived in San Francisco he was welcomed on the field but not in the community.

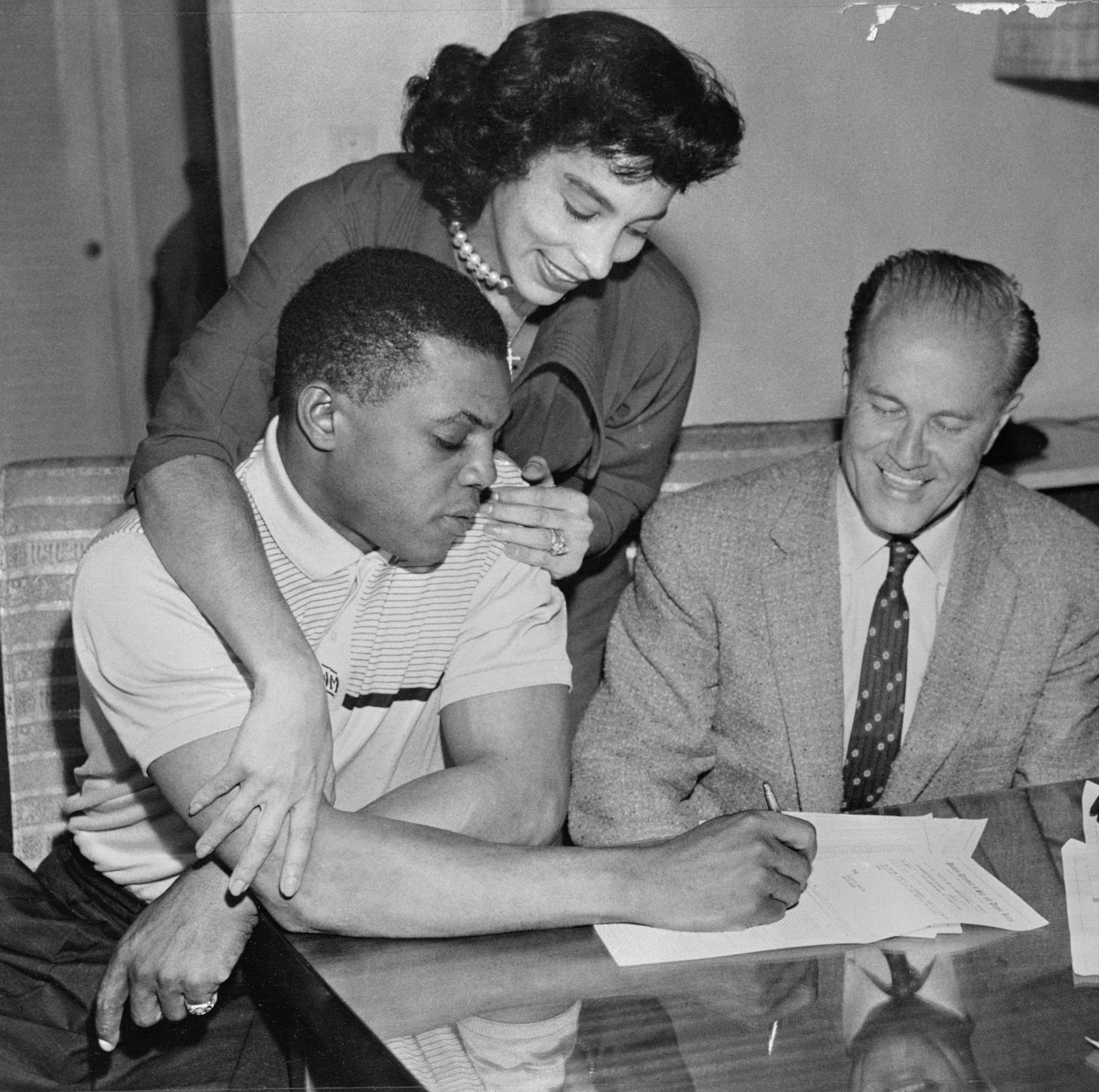

Willie and his first wife Marghuerite attempted to buy a brand-new home in 1957 in the all-white San Francisco neighborhood of Miraloma Park. Willie offered $37,500 in cash to developer Walter Gnesdiloff, who accepted the offer. Then white neighbors organized against the Mays family, and Gnesdiloff backed out, as the San Francisco Examiner explained, “claiming that his business would suffer if it became known that he had sold a property to a Black man.”

Marghuerite said at the time: “Down in Alabama where we come from, you know your place. But up here, it’s all a lot of camouflage. They grin in your face and deceive you.” As Jackie Robinson later reflected about Willie, "They loved his talent, but they didn't want him for a neighbor."

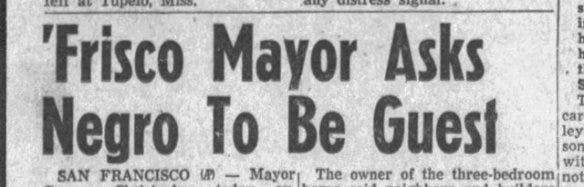

The NAACP got involved, and the mayor of San Francisco scrambled to fix the problem. He desperately invited Mays and Marghuerite to live with him and his family. They said no. After intense scrutiny from the media, and continued pressure from city leaders, Gnesdiloff re-accepted Mays’ offer and the couple purchased the house.

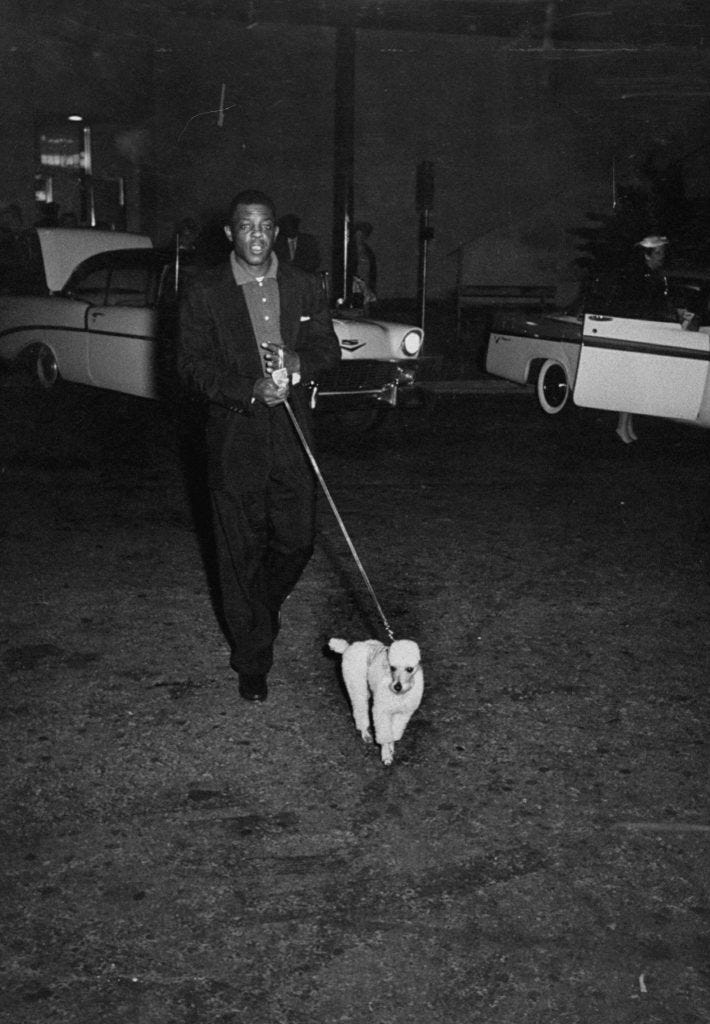

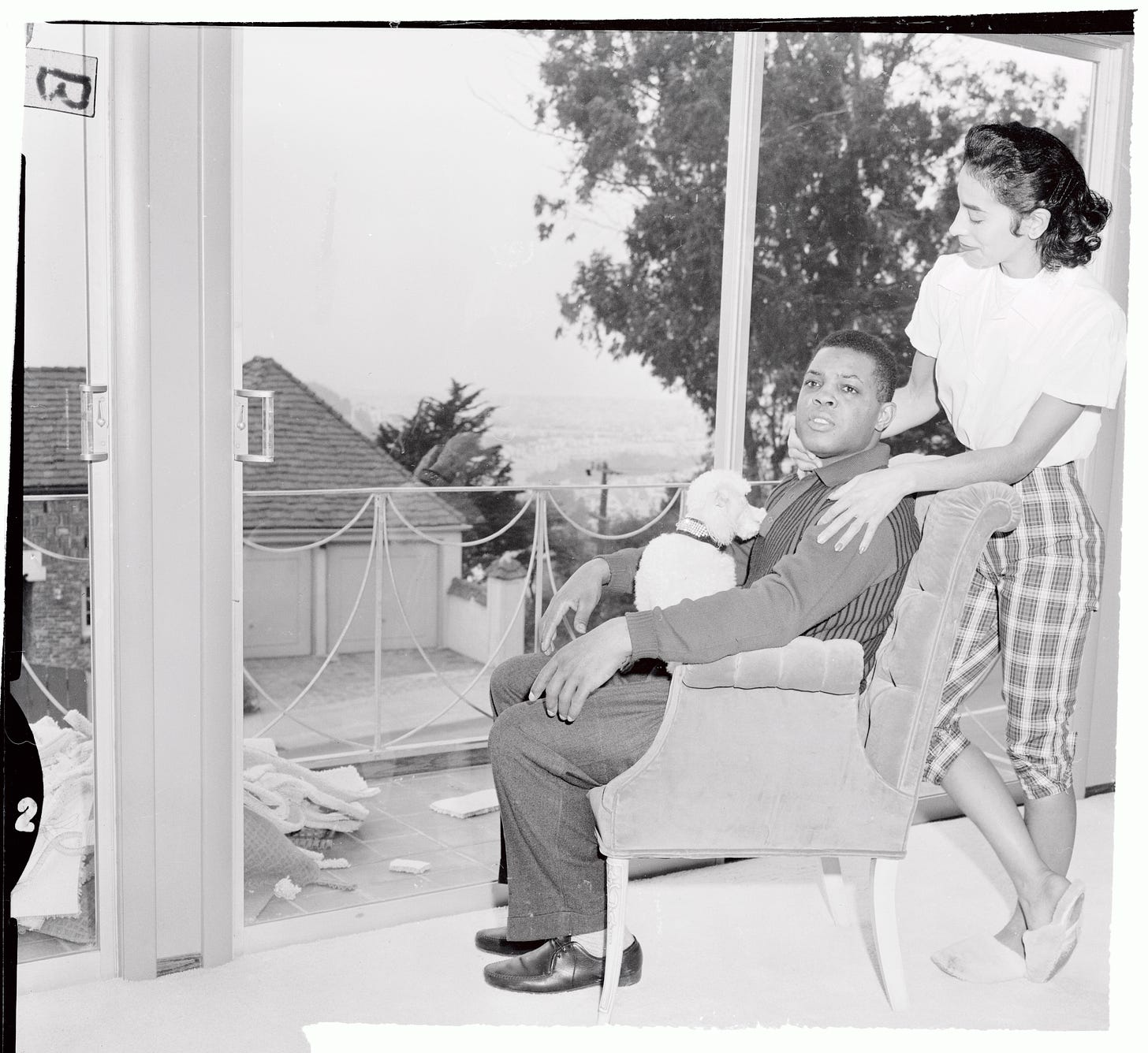

Because the incident received so much media attention, the couple’s move into their home was thoroughly documented. In all of these photos, you’ll notice a third family member: Pepe the poodle.

After the couple moved into their house, the Mays’—especially Marghuerite—reportedly never felt comfortable or welcome in the neighborhood. In June 1959, a fan threw a Coke bottle through their window. Inside the bottle was a note that referenced Mays’ race.

Eventually, Willie and his wife sold that home, choosing to rent homes in San Francisco during baseball season and otherwise live in New York. Here’s a photo of Willie back on the streets of Harlem playing stickball around that time.

Willie and Marghuerite divorced in 1961 and Willie eventually bought a new house in San Francisco and made The City his home.

As recently as ten years ago, San Franciscans could still catch sight of Willie Mays on walks with a white poodle. Here he is heading into AT&T Park with his poodle named “Giant.”

Today, Willie Mays is 92. He is the oldest living member of the baseball Hall of Fame. The great slugger’s eyesight is nearly gone. He can’t drive, and can barely watch baseball games on TV.1 And the house he and Marghuerite first lived in in The City is now worth $3 million dollars.

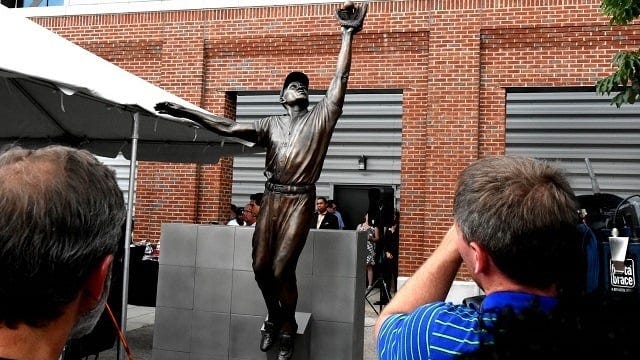

But Willie will live rent free in his adopted city, as well as in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, long after his lifetime comes to a close.

At the front of each of the city’s baseball fields sit big statues of Willie. He’ll remain at these ballparks, standing 9-feet-tall for perpetuity—larger than life, just as he was in his prime. All he’ll be missing is a poodle.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/05/sports/baseball/willie-mays-90.html

This man loved dogs! I appreciate the reports of people seeing Mays everywhere, carrying his poodle around. Sounds eerily familiar...

This is Fucking brilliant. I can't type for the tears. Thank you for remembering one of the two baseball greats -- Clemente being the other.