Art Dogs is a monthly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, turtles, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these posts in your email inbox.

For the last week, I’ve been wandering around London with

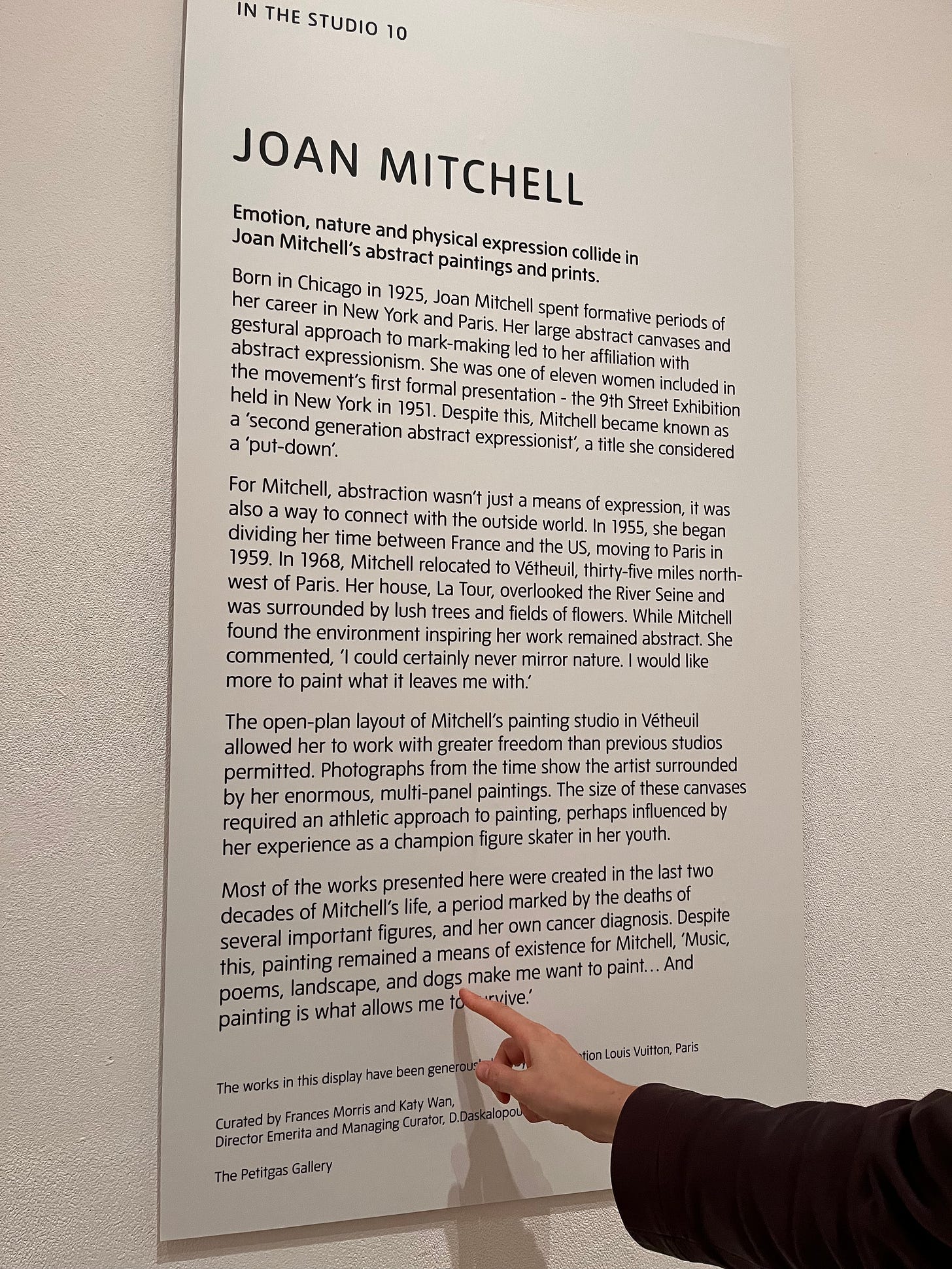

.At some point in every trip to London, I have to visit the National Portrait Gallery and the Tate Modern. (Perhaps this is true for you, too.) I was cruising past a wall text about Joan Mitchell at the Tate when Jess called me over for a closer look.

“Music, poems, landscape and dogs make me want to paint…and painting was what allowed me to survive.” — Joan Mitchell

A quick search led to a treasure trove of archival images of Joan with her many dogs. (She owned 13!)

This Art Dogs was inspired by that chance encounter with Joan and Jess at the Tate. I hope you enjoy learning about her as much as I did.

xo Bailey

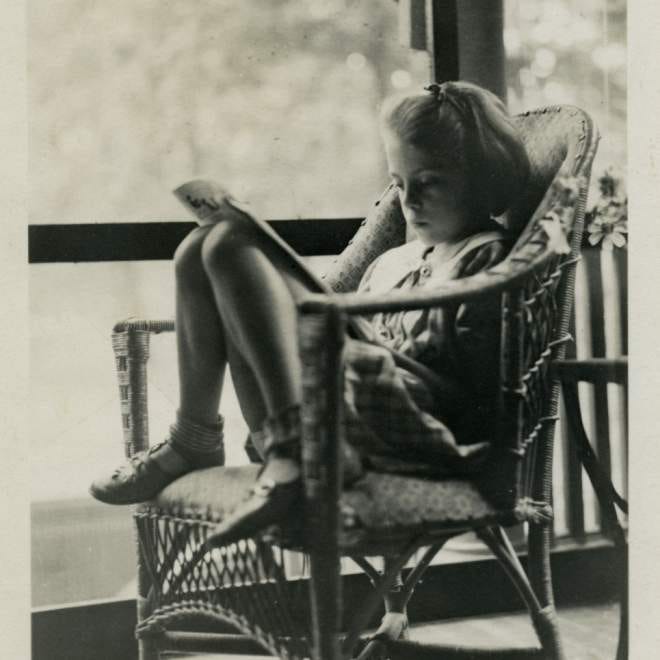

Joan Mitchell was born on February 12, 1925, in Chicago, to a doctor and a poet.

Almost every recollection of her early life includes two details: that she was the daughter of an important poet and editor (her mother, Marion Strobel) and that she was an athlete.

As a young girl, “she came to know T.S Eliot, Ezra Pound, Edna St. Vincent Millay,” and more “as visitors to the family home.”1 She published one of her own poems in Poetry magazine, where her mother was an editor, at just ten years old. Later, she would enroll at Smith College as an English major, marry a famous publisher, and develop friendships with Frank O’Hara (who wrote Lunch Poems in her studio) and James Schuyler.

A childhood spent among poets gave Joan “an abiding lyricism.” She once said that she wanted to express in painting the qualities that “differentiate a line of poetry from a line of prose.”2

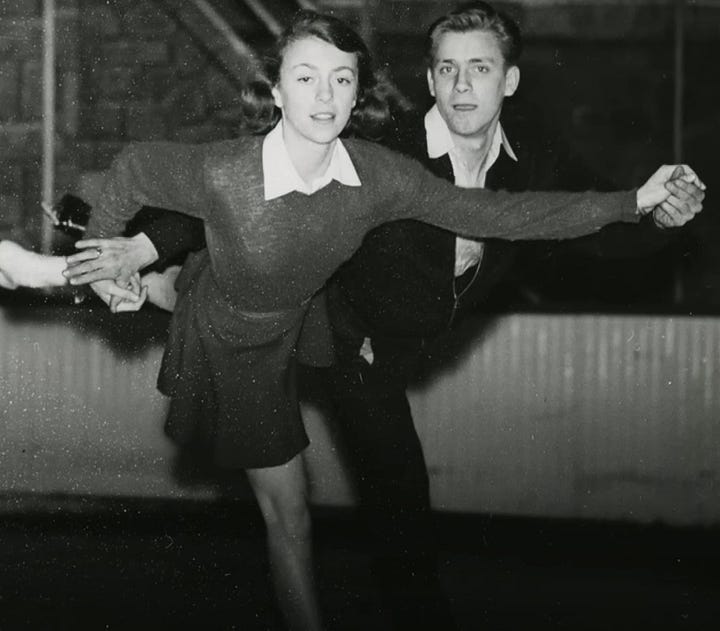

Young Joan was also a jock. Well into her teens, she pursued diving, horseback riding, tennis, and figure skating. She was a champion figure skater, at one time placing fourth nationally and only retiring due to injury. Susan Delson wrote of Joan that “As an artist, she had the virtues of an athlete: ambition, discipline, technique and an intoxicating sense of bodily freedom.” Her brushstrokes are still likened to skating tracks—“rather like a perfectionist’s practice session on the ice.”

Poetry, as with diving, riding horses, and figure skating, strike me as crafts that benefit from bold precision. Expression that demands intention and restraint. Joan Mitchell mastered this capacity as a painter.

Despite the carefree appearance of her brushstrokes, she produced her paintings “slowly, with the help of preliminary drawings in charcoal on the canvas.”3 Joan frequently emphasized her deliberate approach in interviews. “I want to know what my brush is doing,” Joan explained in 1957. Twenty years later, she told Marcia Tucker that her love for structure in her painting was akin to “a kind of plumb line dancers have. They have to be perfectly balanced, the more frenetic the activity is.” John Russell made sure to note this intentionality in the artist’s New York Times obituary:

Throughout her life, she insisted that the tumultuous and airborne expression of feeling in her paintings was not a matter of instinct left free to run wild. As she said to the historian Irving Sandler: “The freedom in my work is quite controlled. I don't close my eyes and hope for the best.” The historian Leo Steinberg once wrote of her ability “to score triumphantly for the willed act as against chance effect.”

Joan is remembered by art history as one of the lone girls in a boys club. Often the only woman in the band of Abstract-Expressionists in New York City, she established herself during America’s artistic emergence in a decade rife with sexism and homophobia.

Joan was well aware that if she’d been a male painter, life would’ve come easier to her. But she forged ahead despite. “When I was discouraged I wondered if really women couldn’t paint, the way all the men said they [the women] couldn’t paint,” Joan remembered. “But then at other times I said, ‘Fuck them.’”

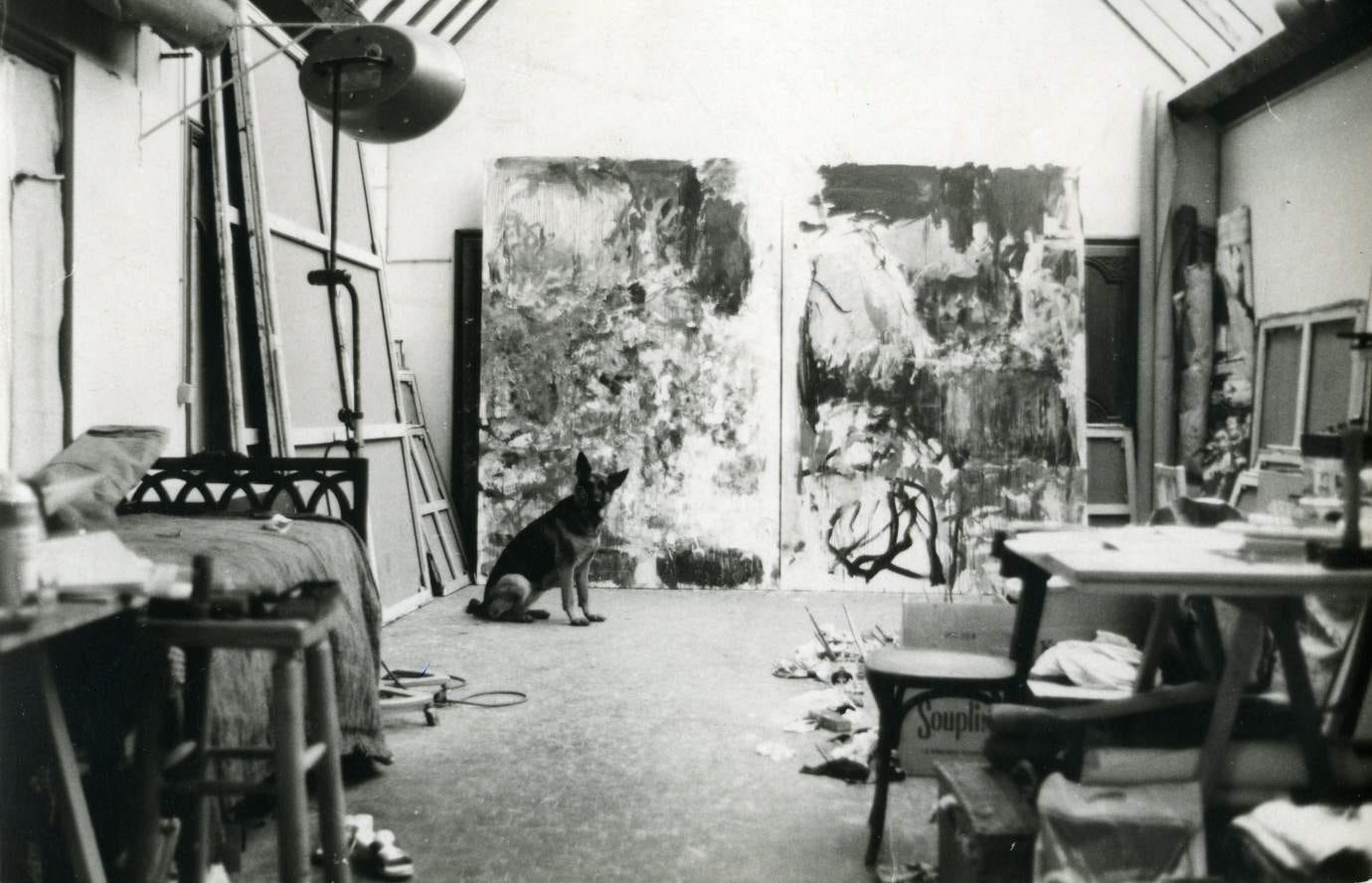

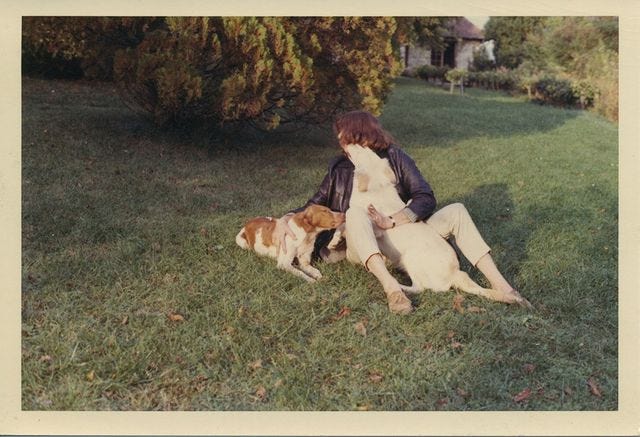

Though Joan was surrounded by male peers and had a number of significant lovers (including Samuel Beckett and Alan Greenspan. Yes, that Alan Greenspan!), her most lasting companions proved to be her dogs. She never had children, but she cared for many, many dogs across her lifetime. The Joan Mitchell Foundation has “1,663 (and counting) photos of puppies and dogs” in their archives, and notes that “Joan titled numerous paintings after dogs dear to her, and she often wrote to friends with news about the dogs in her life.”4

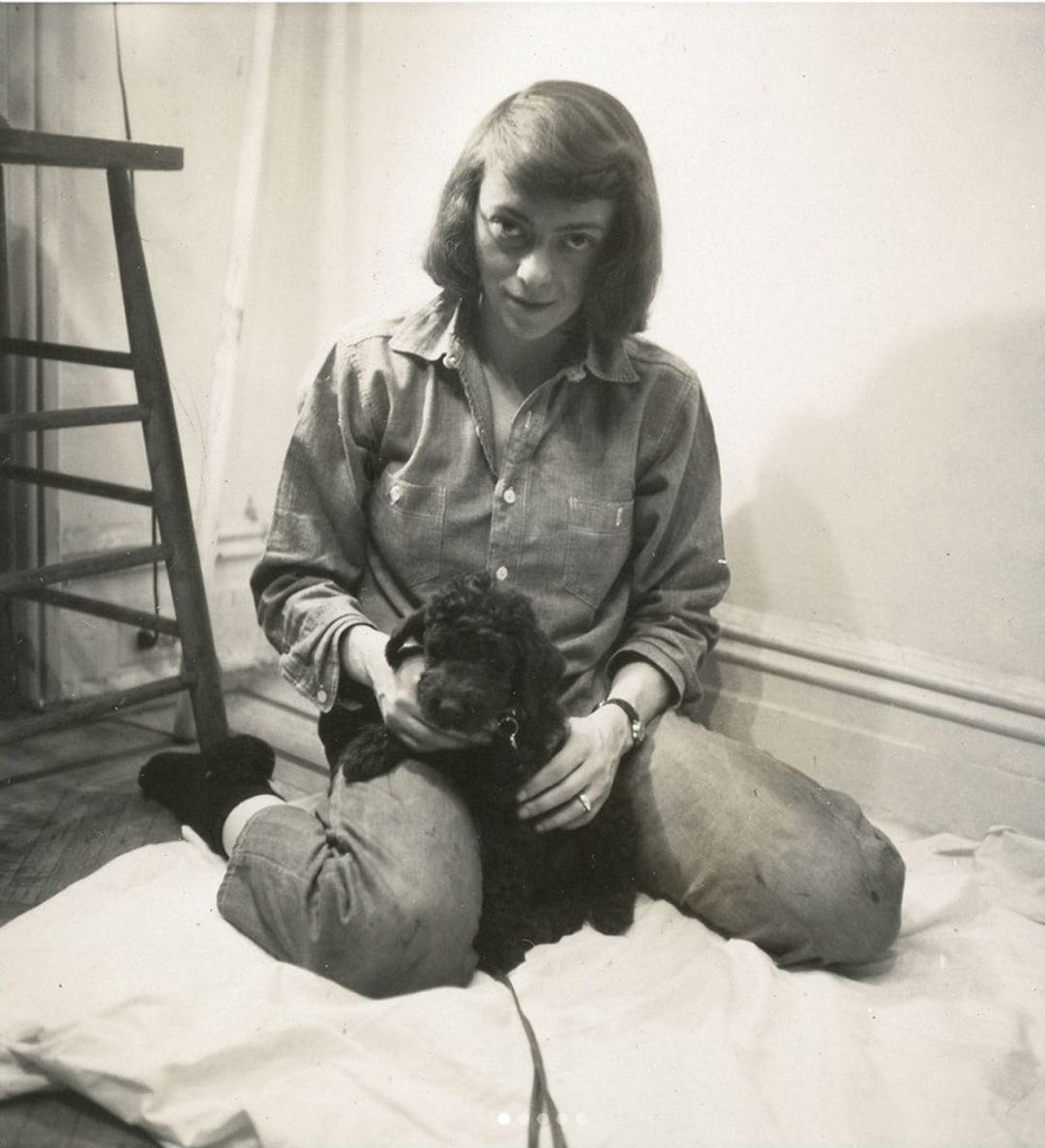

Joan’s first dog was a poodle named Georges du Soleil. Georges came into Joan’s life just after her work was included in the now-historic 1951 “Ninth Street Show” and her first solo show in 1952, which was described by an Art News reviewer as “a savage debut,” with “heroic-sized cataclysms of aggressive color-lines.”5

The art historian Linda Nochlin quotes Elaine de Kooning: “I was talking to Joan Mitchell at a party ten years ago when a man came up to us and said, ‘What do you women artists think . . .’ Joan grabbed my arm and said, ‘Elaine, let's get the hell out of here.’” The mission of Mitchell's animus was to get her out of situations that threatened her freedom. — Peter Schjeldahl

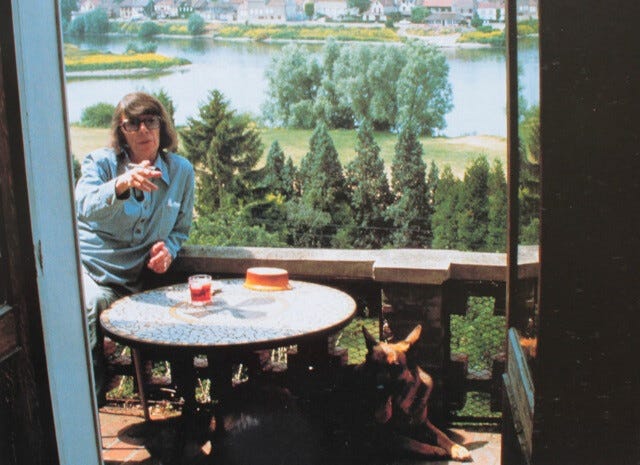

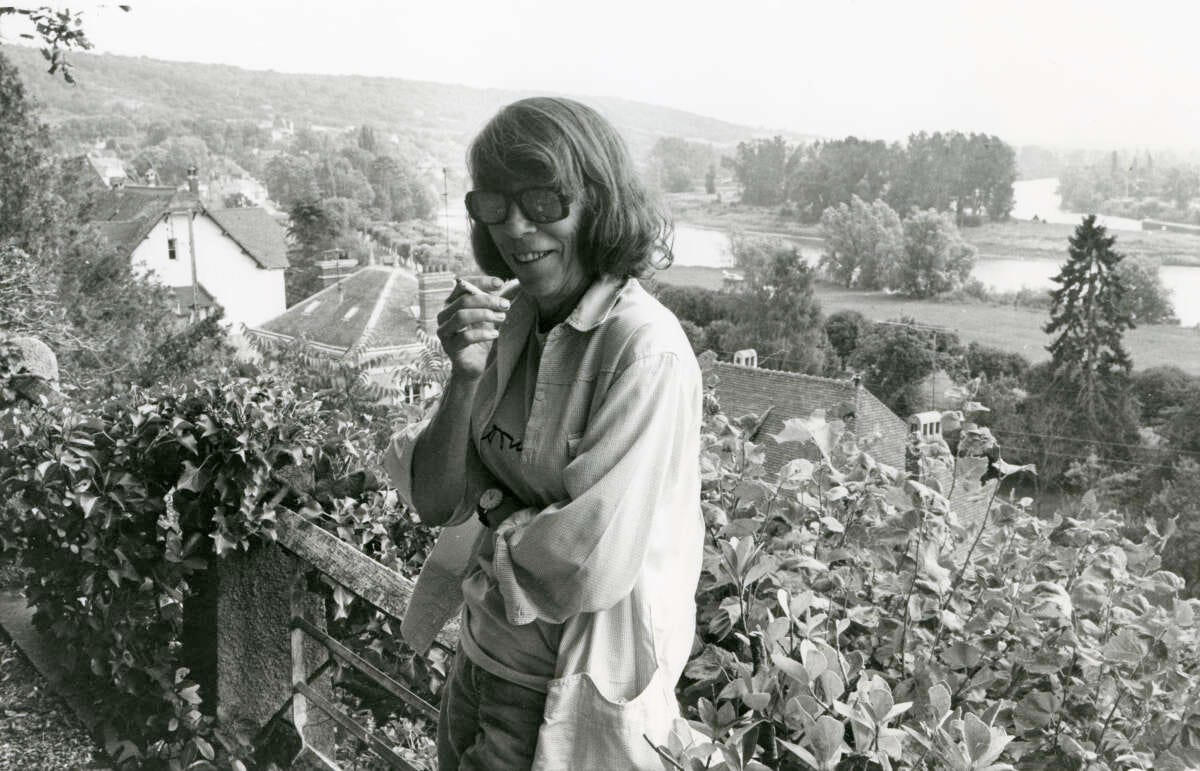

In 1955, Joan began splitting time between New York and Paris. Four years later, she’d move to the country full time—first to Paris, and then to Vétheuil. She lived in the town until the end of her life, close to a house which had been that of Claude Monet before he moved to nearby Giverny. (Her address was “avenue Claude Monet.”)

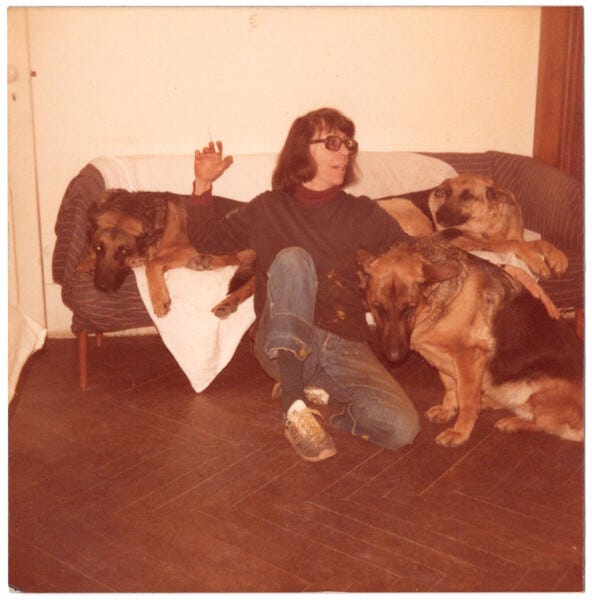

Joan once said that she bought the house in Vétheuil so she wouldn’t have to dog walk, which came in useful because she had so many—three Skye terriers (gifts from Patricia Matisse), three German Shepherds (Iva, Marion, named after her mother, and Madeleine, named after a mistress of one of her exes!), two Brittany spaniels, and a number of stray dogs, totaling 13 dogs across her lifetime.

“I really like trees and flowers and dogs and all that much more than . . . a lot of other people.” — Joan Mitchell

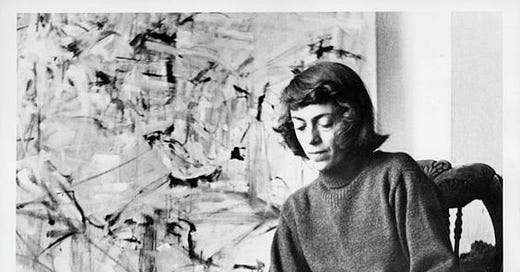

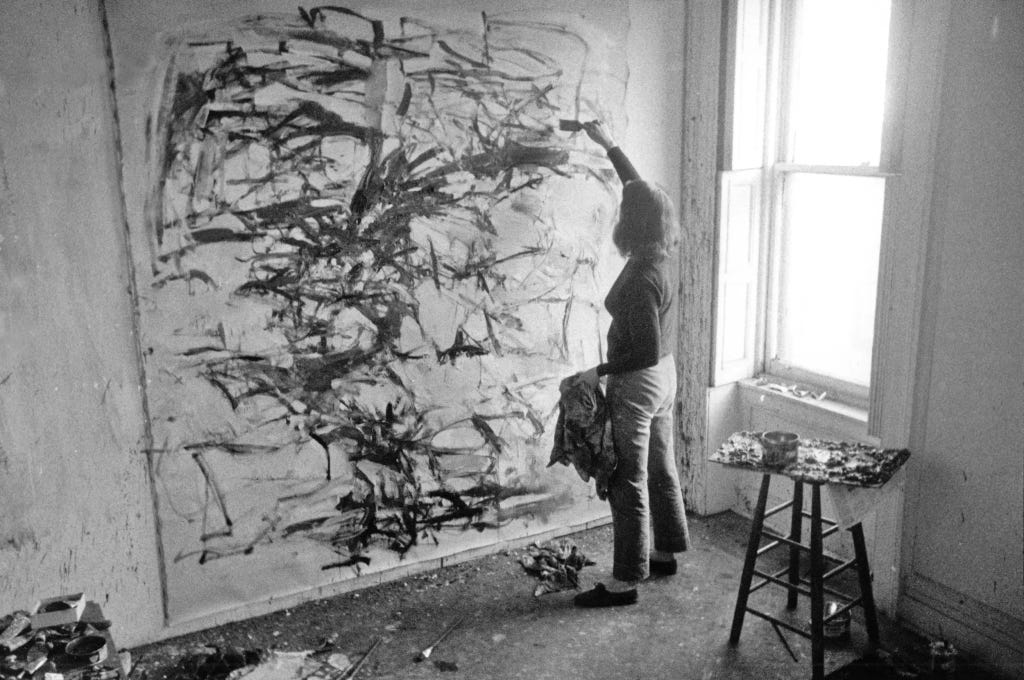

In Vétheuil, Joan “lived and breathed the landscape around her” and receded from the outside world. She had a large studio that allowed her to create on a grander scale than ever before, where Joan would pour the turpentine for her oil paint into leftover dog food cans and leave them scattered across the floor. She liked to paint late into the night and listen to loud music, from Maria Callas to Billie Holiday, with her dogs nearby. The morning after, in the daylight, she reviewed the colors.6

Art Director Suzanne Pagé believes that Joan Mitchell “became herself in Vétheuil.” She was finally free of the gender emphasis that shadowed her entire career in New York and Paris. Eileen Myles noted the following about this period in Joan’s life:

“When I think about Joan in France…she was in a big studio in nature all day long and she had no gender. These paintings have no gender. They are just pure acts of being… I think females were never allowed that freedom except quietly to ourselves.”

Removing oneself from city life eases the social comparisons we endure—in Joan’s case, the ongoing call-out of being a female artist in a male club. She claimed that freedom for herself by moving to rural France alone with her dogs. The resulting paintings are expansive, awe-inspiring. For me, her work in this period rose to new heights—beyond Joan’s mid century Ab-Ex peers and onto the level of Van Gogh and Monet.

If you’ve seen these paintings in person, you’ll know that they are massive—sometimes measuring 9 feet tall by 20 feet wide. John Vincler remarked in The Paris Review that although Joan Mitchell was 5’6 tall and not “unusually proportioned,” she nonetheless “brought an enormity to her painting.”

That’s all the more remarkable given Joan painted these huge artworks while fighting for her life. The late 1970s to the early 1990s was a period of intense grief: She broke off a 25-year, turbulent relationship with her last major lover after his infidelity7, faced unshakeable depression and alcoholism, lost her sister and several close friends in rapid succession, and received a cancer diagnosis that would eventually take her life.

“Painting is the opposite of death. It permits one to survive; it also permits one to live.” — Joan Mitchell

The “Untitled” series (above) were Joan’s last paintings. Reduced to walking with a cane, she would die the same year from cancer. John Vincler looked closely at one of the “Untitled” paintings for his essay The Paris Review:

“Much of its surface remains as white ground, seemingly to emphasize her now-limited reach, documenting the struggles of the body against frailty. But her gestures remain large and bold, lyrical and confident, creating a stark yet riotously colorful composition that suggests calligraphic graffiti… The painting conveys such an immensity of spirit and scale—the persistence of her wingspan—suspended.”

Joan never lost her ambition or discipline. When an art critic asked Joan how she managed to keep painting given her illness late in life, she answered “I just got up on that fucking ladder and told myself, ‘This stroke has to work.’” In her old age, she recognized more than ever “the consequence of every stroke” and “maximized every ounce of energy in service of great painting.” The jock and the poet inside of Joan drove her forward until the very end.

Rest in peace, Joan Mitchell.

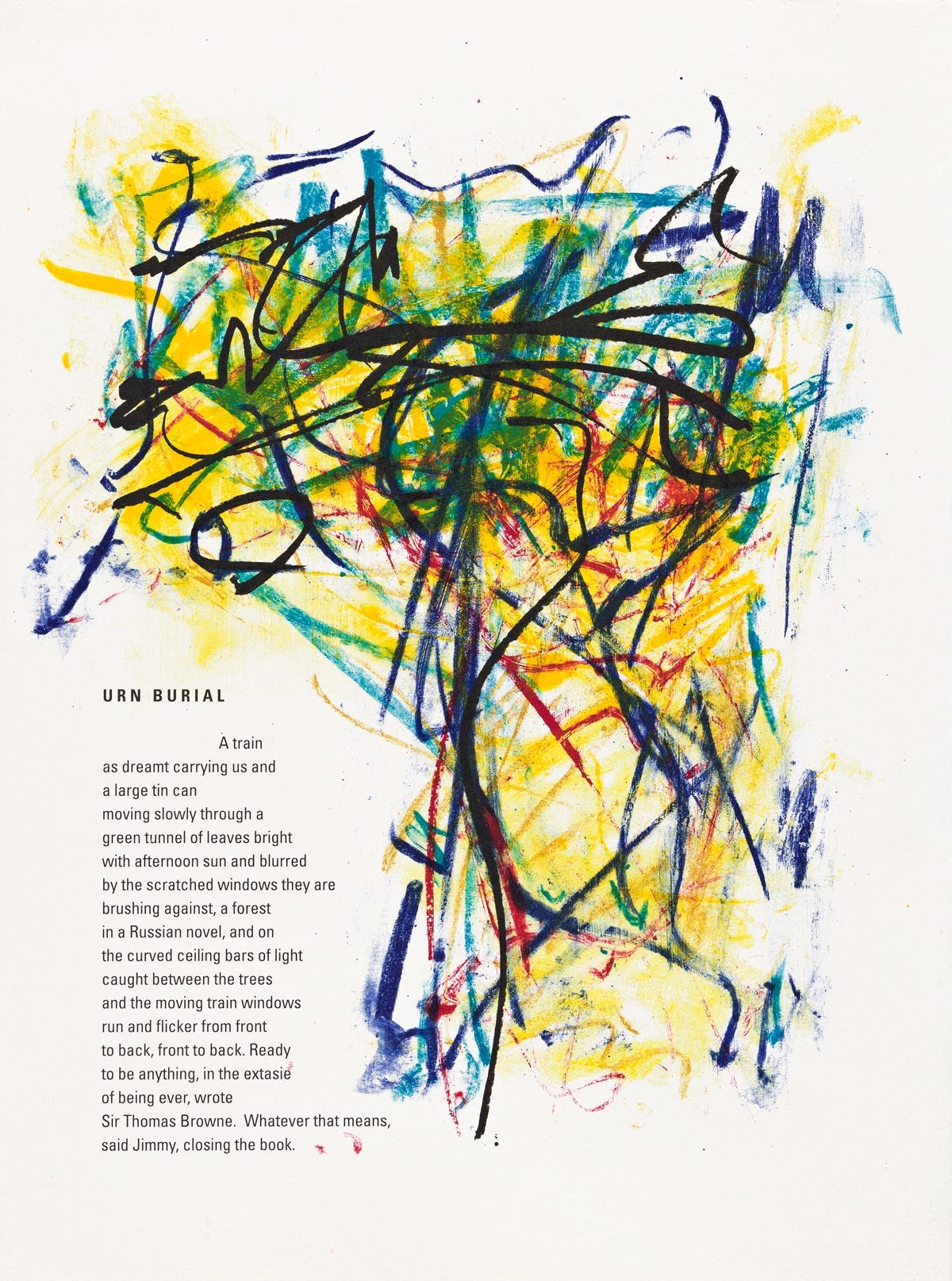

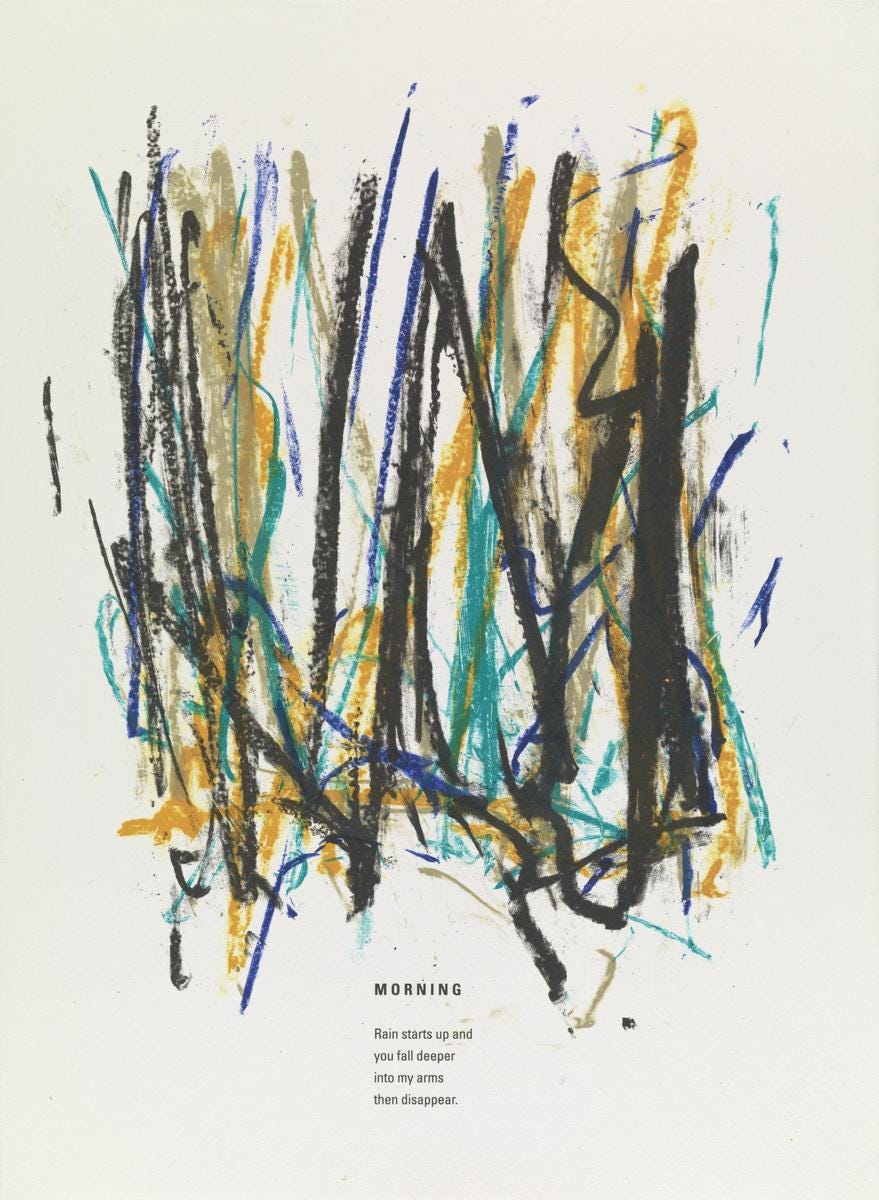

Bonus: Poems

Joan Mitchell paired numerous pastel drawings on paper with typed poems by friends, including Jacques Dupin, J. J. Mitchell, James Schuyler, Pierre Schneider, and Chris Larson. However, she objected to describing these works as collaborations. “I just took the poems,” she said.8 Here are a few I enjoyed most.

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/10/31/arts/joan-mitchell-abstract-artist-is-dead-at-66.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-artist-as-athlete-11629482457

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-04-26-ca-50424-story.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-04-26-ca-50424-story.html

https://www.vogue.com/article/monet-mitchell-fondation-louis-vuitton-exhibition

https://www.hauserwirth.com/ursula/36104-three-women-joan-mitchell-joyce-pensato-elisabeth-kley/: “Ostensibly, I was there to take care of the dogs when Joan was away, but she rarely left the house. Since her messy 1979 breakup with Riopelle she had avoided the town, where they had been notorious for restaurant arguments. Their open relationship endured until Riopelle began an affair right in the house with a young dog sitter who was supposed to be uninterested in men. Joan, devastated, resumed psychotherapy, saying she felt so helpless that she was unable to cross the street. The car in the garage behind the studio was never used. Travel was mostly for exhibitions and gallery meetings. With Riopelle, she had socialized with a broad array of artists, writers, and musicians, but now her world was limited to a small circle of friends.”

Nochlin, AAA “Oral history interview with Joan Mitchell, conducted by Linda Nochlin,” April 16, 1986, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Love Joan Mitchell’s work, saw the show at the Whitney back in 2002, yes, they are massive works. Great to learn about her dogs. Thanks, Bailey.

What a glorious post--deeply researched and felt, chock-a-block with shining examples of her work that bring back memories of the fairly recent retrospective at the Baltimore Museum of Art. So many serious pursuits and interests infused her work--sport and poetry, a nod to dance in one of the quotes. And who could not love the photo of little Joan reading?