Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

I fell for art as an 18 year old standing in front of a Robert Rauschenberg painting at the SFMOMA.

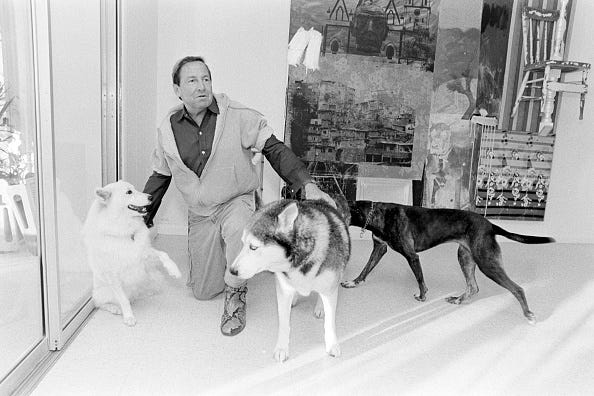

That’s Bob standing with the piece, Buffalo II (1964). He exhibited the canvas at the XXXII Venice Biennale in the spring of 1964, where he was awarded the coveted International Grand Prize in Painting—the first American ever to receive it.

I had no idea who Robert Rauschenberg was before that day. Nor did I know anything about the history of the piece. But within a year, I’d declare as an art history major. Upon graduation, I’d go work at SFMOMA, which led me to join Instagram as one of the first employees. In short, Robert changed my life. I figured it was time I devote an Art Dogs to him, and to Rocky, his companion for more than 40 years.

Robert was born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg on October 22, 1925, in Port Arthur, Texas, an oil refinery town on the Gulf of Mexico, near the Louisiana border. (Janis Joplin was also born there). His father, Ernest Rauschenberg, worked at the local light and power company. His mother, Dora Carolina Matson, was deeply religious. At age 13, Milton decided he wanted to be a preacher, but later changed his mind when he realized that the fundamentalist church his family belonged to forbade dancing, one of his passions.

As a child, he decorated his own room, drawing images on the walls, painting all over the woodwork and furniture, and building “a structure of crates filled with jars and boxes of found objects to divide his side of the room from his much younger sister Janet’s.” Growing up, he had a love for animals, and kept many pets, including ducks, rabbits, frogs, and a goat.1

At Thomas Jefferson High School, Milton participated in the school theater as a costume and set designer. At The University of Texas, Austin, he enrolled to study pharmacology at his parents’ urging, but dropped out in part because he refused to dissect a frog in biology class.2

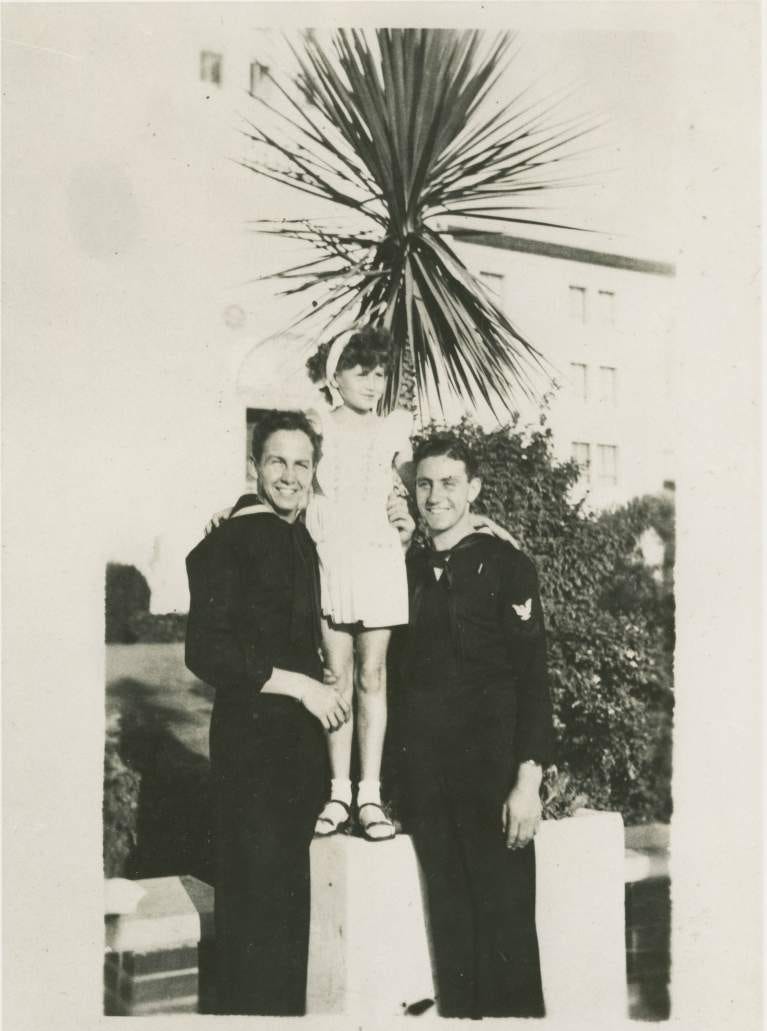

He was drafted into the Navy, but was transferred out for similar reasons: he refused to kill anyone. The Navy moved him to Hospital Corps School for nursing, and Milton later worked in various Naval hospitals in California. While living in Huntington Beach, he saw paintings in the local library that captivated him. Even though he had drawn all his life, Rauschenberg finally realized that he could become an artist. He changed his name to Robert, bought art supplies, and began painting as well as saving up money to study art in Paris.

In Paris, Robert first encountered works by European modernists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. The artwork he saw inspired him deeply, and he spent much of his time painting, often using his hands in lieu of brushes.3

Back in the United States, he followed his girlfriend at the time, Susan Weil, and enrolled at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. He spent the early 1950s moving back and forth between New York, where he joined the Arts Students League, and Asheville for classes. In those few incredible years, he got to know Josef Albers, Leo Castelli, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Ben Shahn, Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, Philip Guston and more. Alongside his peers, Rauschenberg began to create paradigm-shifting artworks.

Soon, he also fell in love with Cy Twombly. Robert and his young wife divorced because of his affair with Cy. Later, the two returned to Europe on a grant—a trip that greatly influenced each of their artistic styles.

One of the most noteworthy of his artworks in these years were his White Paintings, which he exhibited in a joint show with Cy Twombly in 1953 at the Stable Gallery in New York.4 People despised these paintings. The owner of the gallery even had to remove the guest book because people kept writing such mean things in it.5 One critic called them a “gratuitously destructive act.”6

Though the paintings may appear empty, they are not. Their surface reflects the lights and shadows in the environment. John Cage resonated strongly with these paintings, and famously described them as “airports for the lights, shadows and particles.”7 Cage later credited them as inspiration for his composition 4’33.’’

Robert Rauschenberg’s emergence was fueled by the collective and collaborative nature of his early life in New York. He made art first with his wife, then with his partner Cy Twombly, and friends John Cage and Merce Cunningham. In the face of incredible criticism, these peers’ support kept Robert on the path of experimentation and self-belief.

But no collaborator would prove as important as Jasper Johns.

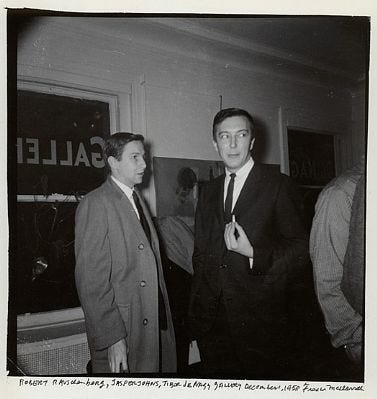

Robert Rauschenberg first met Jasper Johns, who was five years younger, in New York during the 1953 holiday season. They were introduced by Suzi Gablik (a painter friend from Black Mountain College and later an art critic) on a New York street corner near Marboro Books, an art bookstore where Johns worked.8 Months later, they met again at Sari Dienes’s New York studio, where informal salons for young artists frequently took place. They quickly began a deep intellectual, artistic, and romantic partnership. Robert abandoned Cy Twombly for Jasper. Cy, heartbroken, absconded to Rome.

Robert later spoke about how he was knocked over by Jasper Johns: “I have photos of him then that would break your heart. Jasper was soft, beautiful, lean, and poetic. He looked almost ill.”9

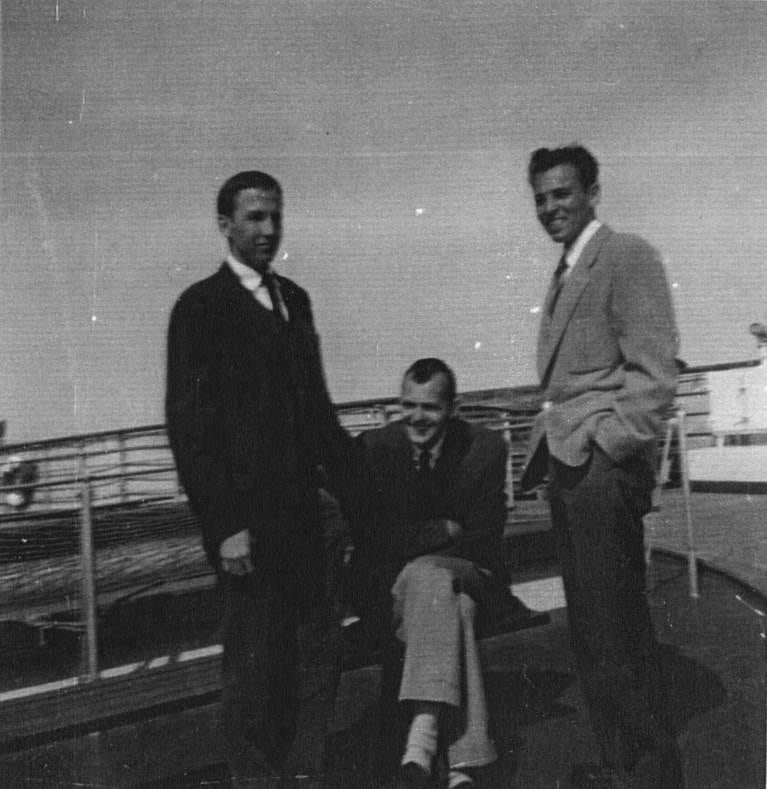

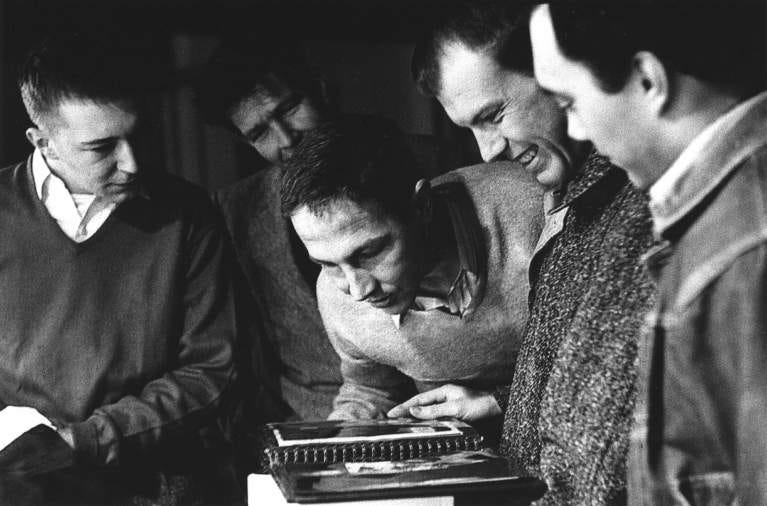

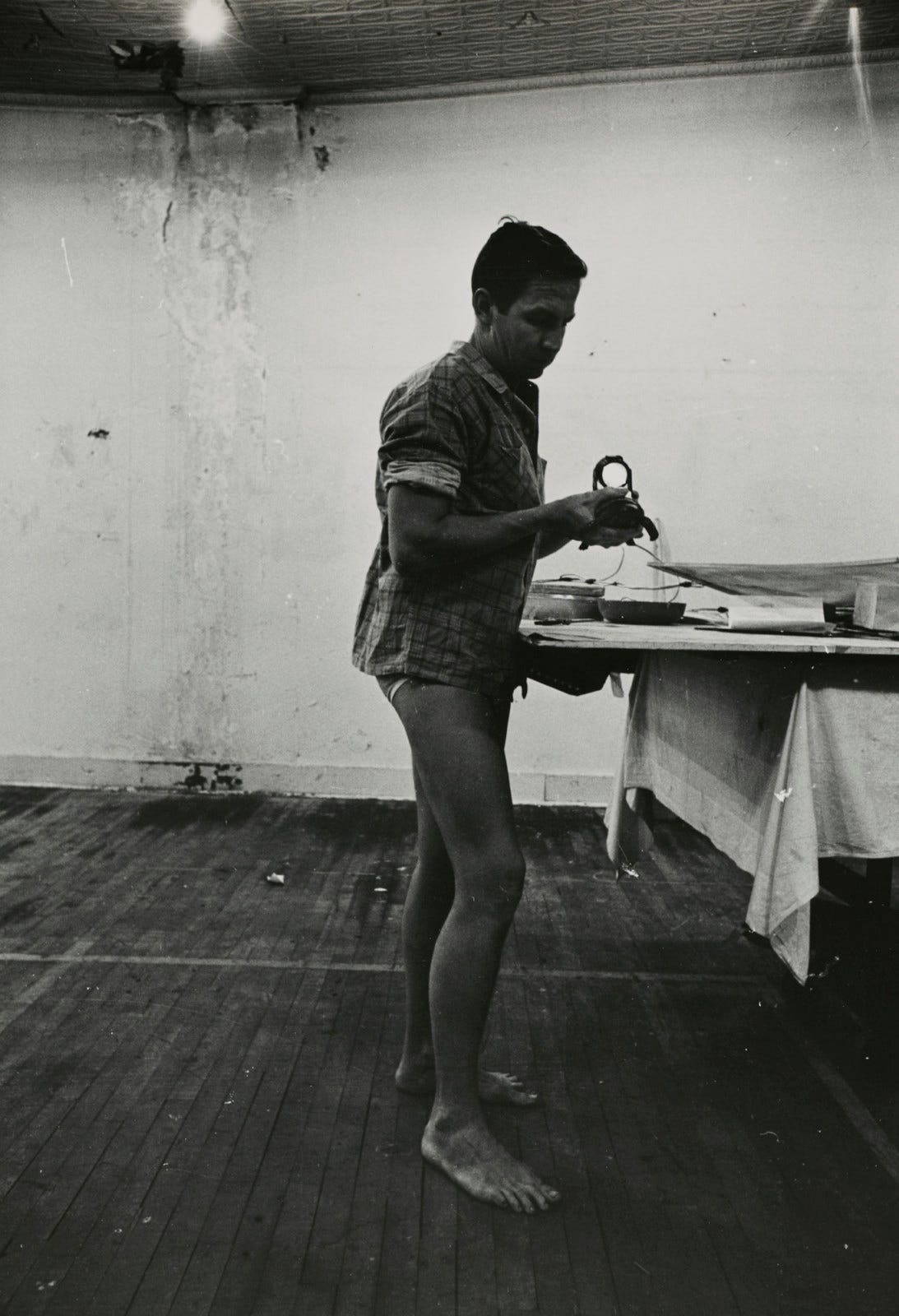

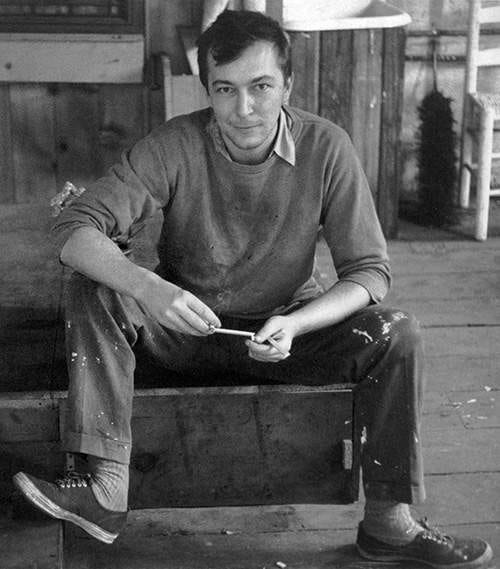

Let’s take a look at some photos from this era.

The photographs above date from an “incredibly fertile period.” Over the course of six years, Robert and Jasper worked in multiple close or adjacent studio spaces in New York, and saw each other daily to exchange ideas and discuss their work.10 They also became close friends with another brilliant avant-garde couple, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Vanity Fair writes that there was a great deal of cross-fertilization between the foursome. “We called Bob and Jasper ‘the Southern Renaissance,’ ” Cage once recalled. “Each seemed to pick up where the other left off. The four-way exchanges were quite marvelous. It was the climate of being together that would suggest work to be done.”

Robert and Jasper both made perhaps their most pivotal masterpieces during this time together.

In 1954, Johns created his first Flag painting on a cut bedsheet, perhaps one that he slept in with Robert Rauschenberg. The MoMA purchased some of his pieces, and Johns’ career skyrocketed.

Robert also made some of his most consequential pieces, including combines such as Bed (1955). MoMA asserts that the bedclothes in Bed are Rauschenberg's own, and that the artist probably slept under these sheets and quilt, perhaps with Johns.11

The New York Times Style Magazine described the impact this period that they spent together had on art as follows:

Most of the subsequent artistic milestones one can think of — from Andy Warhol’s first Campbell’s soup cans in 1962 to Tracey Emin putting her own bed on view inside the Tate Gallery in 1999 to Kerry James Marshall’s use of collage, printing and other variables on the canvases of his early paintings — originated with the work Johns and Rauschenberg produced during these years.12

Though both artists eschew that personal expression shows up in their work, I can’t help but linger on the queer symbols and secrets within these two pieces. A queer bed, and a queer American flag, hanging on the wall as canvases. At the time, homosexuality was illegal in the United States, and critic Jonathan Katz described the 1950s as “the most homophobic [decade] in the twentieth century.”13 Though the men were out to their peers, they have never spoken explicitly on the record about their relationship. They never uttered terms such as “gay,” “lover,” “boyfriend,” or “homosexual” about one another, though their relationship has been confirmed in recent years.

By 1961, Rauschenberg and Johns were drifting sourly apart. Later, Robert Rauschenberg explained that the two split up in part because of his discomfort as they became known beyond their immediate circle. “What had been sensitive and tender became gossip,” said Rauschenberg.

The break up was so bitter that they didn’t speak for years and, according to biographers, each left New York City for an extended period. Jasper bought a beach house on Edisto Island, south of Charleston, South Carolina, where just four families lived year round. A year or so later, Robert started spending time on an island in Florida called Captiva where there was only one telephone to the mainland and one policeman for about 50 families.14

From his remote island in South Carolina, Johns made revenge paintings, including one canvas called Liar. In 1961, as the relationship was ending, Johns also titled another painting In Memory of My Feelings — Frank O’Hara, taking its name from a well-known poem by O’Hara about gay love and the price paid for suppressing it. The poem begins, “My quietness has a man in it.”15

While Johns was conjuring revenge paintings, Rauschenberg surrounded himself with a new lover—dancer Steve Paxton16—and a cadre of pets, including a desert turtle named Rocky, a dog named Laika (yes!), and a kinkajou named Sweetie.

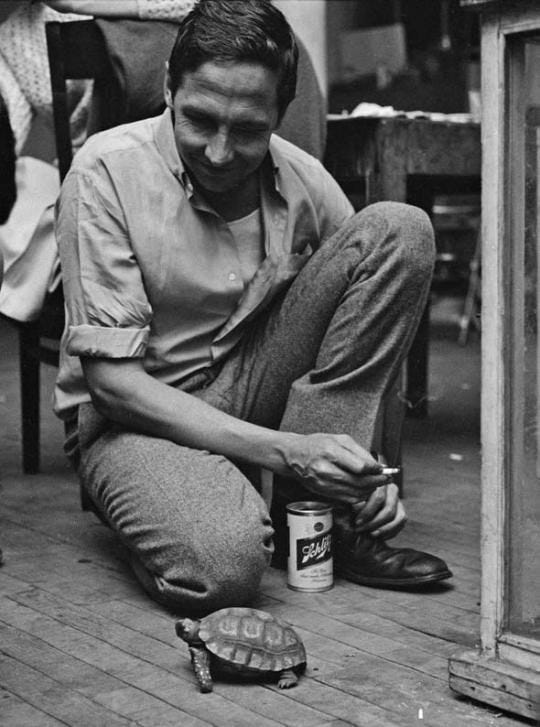

Rocky is my favorite of Rauschenberg’s post-Johns companions.

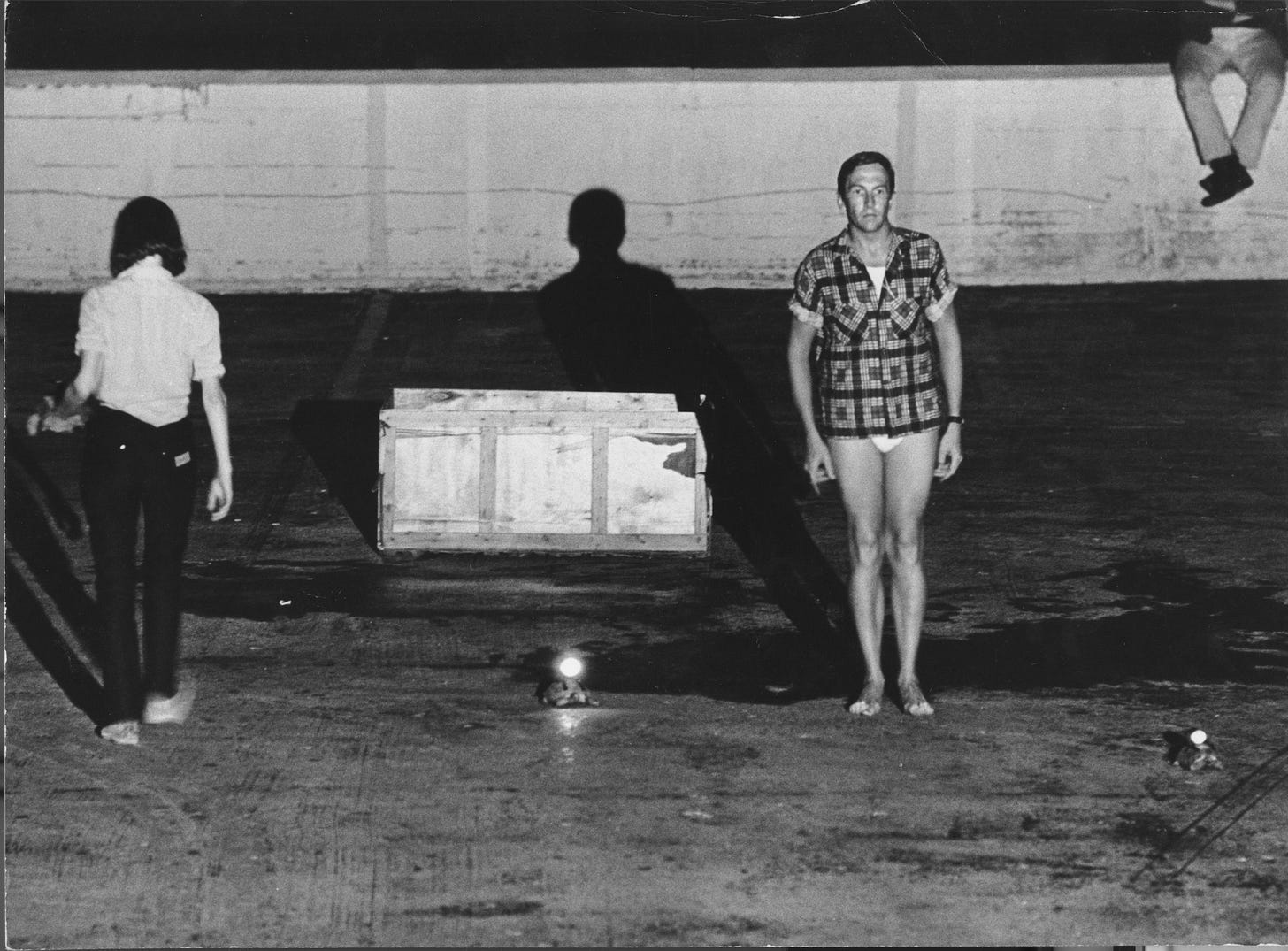

He was one of nearly three dozen turtles that Rauschenberg rented from an animal store to create a 1965 performance piece called “Spring Training.” Thirty-three turtles were let loose on a darkened stage with flashlights taped to their shells. (See below)

Robert took Rocky home with him after the performance. He could often be found thumping around the studio kitchen. When Rocky was hungry, he reportedly would walk to the refrigerator and beg to be fed.

Rocky would play witness to the rest of Robert’s life. The turtle lived at his studio from 1965 until 2008. Robert passed that year, and Rocky followed within three months.

Though Rocky was Rauschenberg’s steadiest and longest-term companion, as an artistic collaborator he proved lacking. A common critique of Rauschenberg is that he “stopped breaking new ground around 1965”—the same year when Rocky came into his life.17 Though Rauschenberg was “a staggeringly prolific artist,” who worked until he died in 2008, almost all the work in his MoMA show in 2017 dated from 1964 and earlier. Louis Menand wrote: “Rauschenberg’s work after that is often, in spite of itself, on the edge of the decorative or the documentary; it has lost much of its transformative capacity.”

While it can be difficult to define why an artist’s career takes a turn like that, some have ventured to guess. The title of the MoMA retrospective from 2017 was “Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends.” The New Yorker recalls:

At the start, it was the collective and collaborative nature of Rauschenberg’s art-making, first with his wife, then with his partners Cy Twombly and, after Twombly, Jasper Johns, and especially with Cage and Cunningham, that nourished his creativity. He broke up with Johns in 1962, and with Cage and Cunningham in 1964, not long after his big win at the Biennale. He worked with other artists many times afterward, but his font of originality had run dry. The run was remarkable while it lasted.

Rauschenberg’s art dimmed as his key creative relationships dissipated. No number of loving but silent pets or island seclusion could replace that special crew of art friends and lovers that fueled Rauschenberg’s great experimental triumphs in the 1950s and 1960s.

That's why I like dance, music, theatre, and that's why I like printmaking, because none of these things can exist as solo endeavors. Also, the best way to know people is to work with them, and that's a very sensitive form of intimacy. — Robert Rauschenberg, 1977

What can we learn from this story?

I hope it’s to find and fight for the right kind of intimacy, not shy away from it.

I’m reminded of painter Agnes Martin’s concept: “Friends of Art.” Agnes argued that artists must be careful about whom to let close to their work. A careless comment by a contextless stranger can cut deeply, derailing a promising project or process, and the artist should build a forcefield against such feedback. “Indifference and antagonism are easily detected,” in studio visitors, Agnes wrote. “You should take such people out immediately.”

However, Agnes believed “there are some people to be allowed into the studio” who “will not destroy the atmosphere but will bring encouragement and who are an absolute necessity in the field of art.” “They are not personal friends,” Agnes goes on. “They are Friends of Art.”

Friends of art are people with very highly developed sensibilities whose inspiration leads them to devote their lives to the promotion of art work and to bringing it before the public.

John Cage and Cy Twombly were key “Friends of Art” for Robert Rauschenberg, who faced much criticism at the outset of his experimental career. But Jasper Johns was perhaps the ultimate “Friend of Art,” for him.

Before he died in 2008, Rauschenberg said that he and Johns “gave each other permission.” No matter how many turtles, dogs, and kinkajous he surrounded himself with, or studios and programs he built around himself, nothing in Robert Rauschenberg’s life would ever come to replace the conversations that he and Jasper Johns had in their adjacent studios, and in their bedsheets, in private. Conversations we’ll never know the contents of, but that art history will enjoy the fruits of for centuries to come.

In Memory of My Feelings — Frank O’Hara by Jasper Johns (1961)

You can read a New York Times piece analyzing the connection between Frank O’Hara, his poem, and Johns & Rauschenberg’s love here.

https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/chronology

ibid

ibid

Bernstein, Roberta. Introduction to Rauschenberg: The White and Black Paintings 1949-1953 (New York: Larry Gagosian Gallery, 1986).

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/how-to-look-at-a-rauschenberg

James Fitzsimmons, “Art,” Arts and Architecture 70 (1953): 9, 32-35.

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1961/1973), 102.

https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/chronology

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/feb/12/valentine-day-ust-heartbreak-suggestive-sculpture-arts-greatest-love-triangle-twombly-jasper-johns-rauschenberg

https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/chronology

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78712

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/18/t-magazine/jasper-johns.html

https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/rauschenberg-affection/

https://www.vanityfair.com/magazine/1997/09/rauschenberg199709

http://www.fredbernstein.net/articles/rauschenberg-and-johns/

This is suggested by Calvin Tomkins’s reports of his numerous visits to the studio to interview Rauschenberg for his essay “The Sistine on Broadway,” first published in 1980 in Tomkins, Off the Wall, 192–200. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.302/essay/scanning/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/05/23/everything-in-sight

This was very good. I had forgotten about Rauschenberg! I aaaaaalmost minored in art history - took and enjoyed a bunch of required classes in my painting and printmaking major, and added some electives too, but I think I decided to graduate instead. I still loved all that art history, though.

The avant-garde artists of the 50s had so much BS to deal with. It's just incredible, but it also explains a lot about how they were so transformative and creative in such a short window of time: being under the gun of oppression combined with having enough resources to create art, and a culture that celebrated the art they were making, even if only for a few short years.

What serendipitous timing! I was just reading today on Rauschenberg (and Agnes Martin!) in Olivia Laing’s “Funny Weather” collection of essays. 🐢🤍