Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

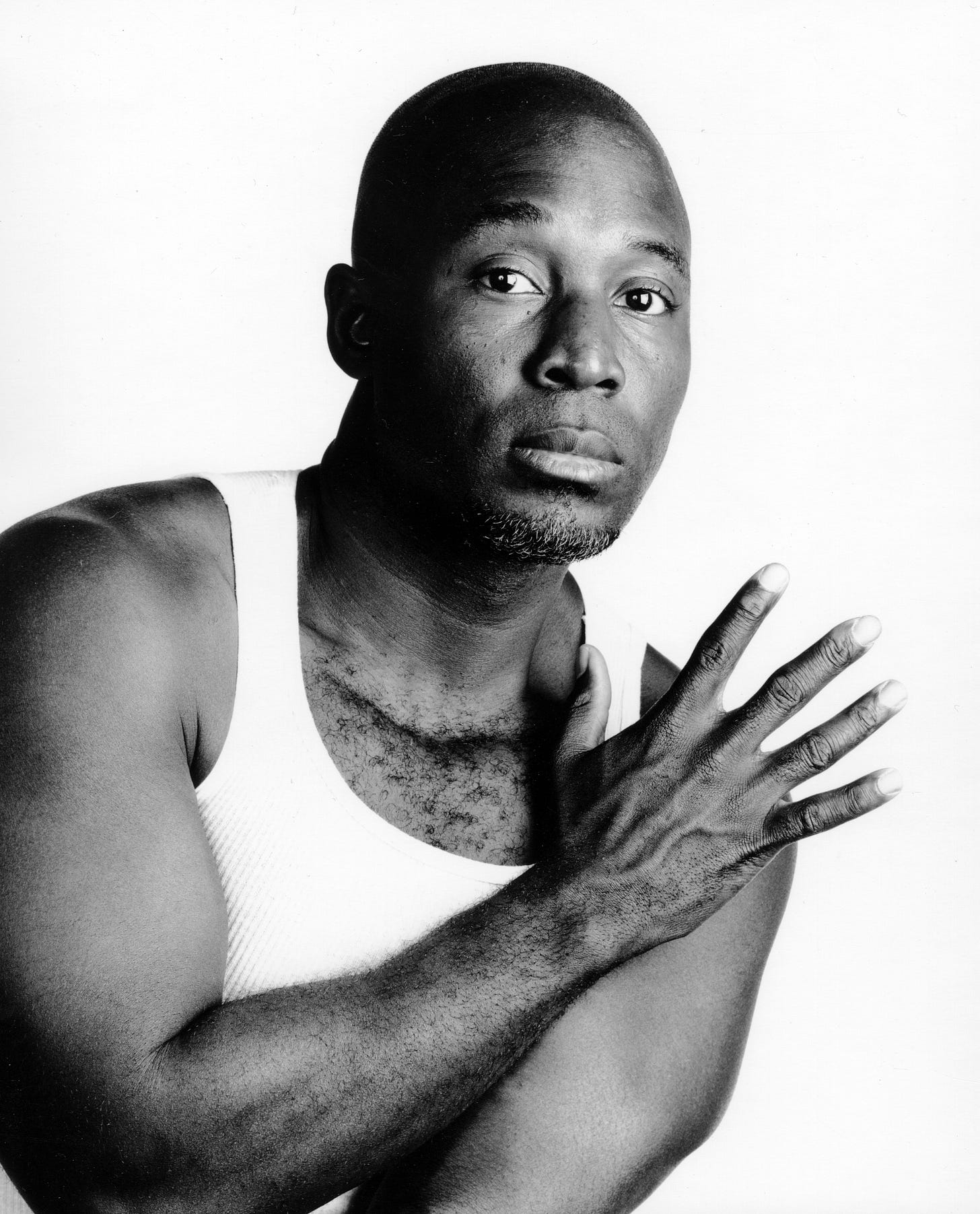

Nick Cave is an American sculptor, dancer, performance artist, and professor. The New York Times has called him “the most joyful, and critical, artist in America” as well as “one of that select group of artists, like Jeff Koons or David Hockney, who is celebrated by both high art and popular culture.” He’s had retrospectives at major museums, including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and is best known for his Soundsuit series: wearable sculptures that are often made with found objects.

Words don’t do these Soundsuits justice. I recommend you enjoy this video before reading any further:

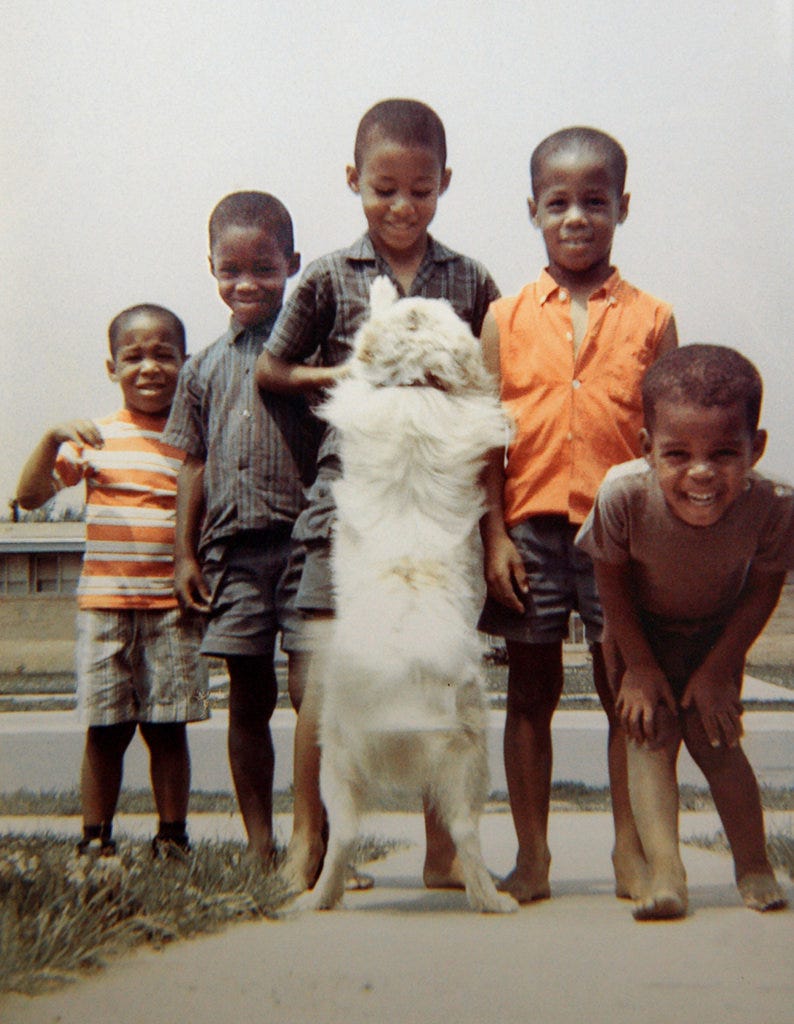

Nick Cave was raised in public housing in central Missouri. He was the second of seven brothers, all one year apart. His parents split up when he was young, so his mother raised the seven boys alone. As a profile of the artist in T Magazine describes, in the house “personal space was limited but respected, a chart of chores was maintained, and creative projects were always afoot.”1

Nick attributes his mother, Sharron, with fueling his career by responding so enthusiastically to his earliest artworks and his interest in fashion.

Growing up, I would make my mother stuff 24/7 — things like halter tops and macramé accessories back in the day, all of which she wore proudly, or just something simple like a card. But whatever it was, my mother never said, “Thank you sweetie. It’s cute. I like it. Love you.” Her response was always so exaggerated, so enormous in terms of intensity that it made me feel like it was the most extraordinary thing she’d ever had in her life.

His aunts are seamstresses and his grandmother was a quilter, and the boys used that in-house wisdom to their advantage. “When you’re raised by a single mother with six brothers and lots of hand-me-downs, you have to figure out how to make those clothes your own,” he told The New York Times.2 To remix his brothers’ jacket into something new, for example, he would “take off the sleeves and replace it with plaid material.” Thus at a very young age, the artist was already cutting apart and putting fabric back together, or as he says: “finding a new vocabulary through dress.”3

Sharron managed the household on one income, but no shortage of creativity and joy. Nick recalled during a particularly tight month, his mother came home from work one day and realized that there was no food left in the house except for some dried corn.4 In an effort to “camouflage” the lack of food for her children, she made a party out of the situation, showing her sons a movie on television and popping the corn. The kids never registered that something bad was happening, even though they knew there was nothing to eat. “It doesn’t take much to shift how we experience something,” Nick Cave explained. “It’s nothing, but it’s everything.” He has said that those moments of “fantasy" and “belief” in his childhood inform how he creates art today.

In 1979, when he was just two years out of high school, Nick Cave met Alvin Ailey. He would go on to spend several summers in New York studying with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. After graduating from college with a BFA, he designed displays for the Macy's department store and worked as a fashion designer while maintaining an interest in art and dance.5

Nick felt moved to create his first Soundsuit in 1992 in response to the Rodney King police beating. “It was a very hard year for me,” he said. “I started thinking about myself more and more as a black man as someone who was discarded, devalued, viewed as less than.”6 Amidst this time of reflection, one day he saw a twig on the ground in Grant Park in Chicago. “I just thought, well, that’s discarded, and it’s sort of insignificant,” mirroring feelings he was having about how society viewed his own worth. He started gathering the twigs by the armful.

The artist went back to his studio and began cutting these small branches into short sticks. He drilled holes through hundreds of them, threading wire through each stick then attaching them to a garment. As soon as the first Soundsuit was done, Nick realized that he could wear it as a second skin: “I put it on and jumped around and was just amazed.” he told The New York Times. “And because it was so heavy, I had to stand very erect, and that alone brought the idea of dance back into my head.”7

“When you wear this particular Soundsuit, it makes this amazing sort of rustling sound. It’s almost as if you are sort of—imagine running through the forest, and you’re running over twigs and leaves during the fall. And so it’s that kind of rustling, sort of earthy sound that it makes.”8

“The sound was a way of alarming others to my presence. The suit became a suit of armor where I hid my identity. It was something ‘other.’ It was an answer to all of these things I had been thinking about: What do I do to protect my spirit in spite of all that’s happening around me?”9

To date, Nick Cave has made more than five hundred Soundsuits, and they have only gotten more flamboyant.

“I have to feel like this looks,” the artist once told a New York Times reporter while pointing to one of his “Soundsuits” covered in exuberantly colored synthetic hair.

Nick Cave says that the most meaningful part of his work today is no longer making pieces himself. It’s collaborating. As The New York Times wrote, “the art that interests Cave is the art he inspires others to make.”10

He has spent recent years welcoming underprivileged children to lead his Soundsuit performances. He recalled in an interview how, when kids learn to stand up and move in his 40-pound suits of armor, the works can make them “look — and feel — like shamans.”11

In 2018, he and his husband Bob Faust12 purchased a 24,000-square-foot former factory in Chicago. Together, they turned the space into expansive studios called “Facility,” a name meant to emphasize its purpose of facilitating projects amongst collaborators. There’s a front gallery where work by young artists is visible from the street (an ode to Nick Cave’s first job designing window displays for Macy’s13). They’ve established an art competition, prizes for Chicago Public School students, and funded a special award for graduate fashion students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “There are lots of creative people that do amazing things but just have never had a break,” Nick Cave explained. “And so to be able to host them in some way, these are the sort of things that are important to us.”14

Faust’s daughter, Lulu, lives above the studios with Nick, Bob and their dog, Bam-Bam, as does one of Nick Cave’s brothers, Jack, a fashion designer. The home is full of art from friends, both now-famous artists like Kehinde Wiley (a dog lover!) and Kerry James Marshall (a bird enthusiast!), as well as art from Nick Cave’s students, whose work he frequently purchases. “I remember someone bought a piece of mine when I was an undergrad,” he explained. “That validation and motivation — it’s just what that does to a young person.”8

Community and collaboration seeps so deeply through Nick Cave’s life that when W Magazine wanted to photograph the Facility space and his clothes, Nick Cave requested the shoot include a dozen of their friends, family members, art fabricators, and museum benefactors alongside a mix of the magazine’s professional models.

And yes, their dog Bam Bam made the cut, too.

Five years ago, I attended Nick Cave’s epic performance work “The Let Go,” at the Park Avenue Armory. The piece was inspired by Nick Cave’s youth, when he went multiple times a week to dance in disco clubs. He has said these clubs helped him survive college and graduate school in the midst of the AIDs crisis and racial strife. “I would go into the club and I would just work it out on the dance floor,” he said. “I wouldn’t talk to anyone and I would dance for about three hours.”9

“The Let Go” demonstrates the effort the artist is willing to invest in order to shine his spotlight on collaborators. Nick Cave invited more than 90 community groups to help him realize the work. Even the audience became co-conspirators. After performances, and on weekends, ticket-holders could show up and dance, too.

One dancer explained to a reporter that the show’s purpose was to remind us that we can choose one of two paths in our lives: be discouraged and tormented “or have the audacity to say, ‘I’m not going to let this break me.’” Other performers used the word “empowerment” to describe the impact of participating in the show. And one visitor said of their experience at “The Let Go”: “It’s definitely pushing you toward freedom.”10

Though it may seem heavy handed, I can’t help but see the traces of Nick Cave’s childhood in all of these late-stage works and collaborations.

His mother Sharron’s knack for turning the mundane and challenging into moments of fantasy shows up in his exuberant performances.

The hand-me-down fabrics he repurposed to create clothes as a young kid inform his Soundsuits made of twigs, buttons, safety pins, sock monkeys, and sweaters.

Their family’s rambunctious, buzzing house resembles Facility, a community hub where he now lives and works, and invites others to do the same alongside him. (Pet dogs included!)

And his mother’s support for Nick Cave’s early creative efforts preceded the encouragement that he now offers to young artists.

His special upbringing created the conditions that led to Nick Cave’s artistic rise—an emergence that was far from preordained as a black, gay man navigating poverty, AIDs, and all of America’s racial iniquities.

And now, Nick Cave offers to us what his mother once offered to him and his brothers: He helps protect our spirits in spite of all that’s happening around us.

If you want to tap into some Nick Cave-induced freedom this Friday afternoon, there’s only one thing left for you to do.

Dance.

Don’t worry. He’s created a guide for us.

“It doesn’t take much to shift how we experience something. It’s nothing, but it’s everything.” — Nick Cave

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/15/t-magazine/nick-cave-artist.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/05/arts/design/05fink.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWhen%20you're%20raised%20by,brother%20Jack%2C%20a%20Chicago%20designer.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/15/t-magazine/nick-cave-artist.html

ibid

https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/nick-cave-38

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/05/arts/design/05fink.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/05/arts/design/05fink.html

https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/asmr-soundsuit-2011

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/15/t-magazine/nick-cave-artist.html

Here’s an excerpt from a NYT profile documenting all of Nick Cave’s recent collaborations:

In 2015, he trained youth from an L.G.B.T.Q. shelter in Detroit to dance in a Soundsuit performance. The same year, during a six-month residency in Shreveport, La., he coordinated a series of bead-a-thon projects at six social-service agencies, one dedicated to helping people with H.I.V. and AIDS, and enlisted dozens of local artists into creating a vast multimedia production in March of 2016, “As Is.” In June 2018, he transformed New York’s Park Avenue Armory, a former drill hall converted into an enormous performance venue, into a Studio 54-esque disco experience with his piece — part revival, part dance show, part avant-garde ballet — called “The Let Go,” inviting attendees to engage in an unabashedly ecstatic free dance together: a call to arms and catharsis in one. Last summer, with the help of the nonprofit Now & There, a public art curator, he enlisted community groups in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood to collaborate on a vast collage that will be printed on material and wrapped around one of the area’s unoccupied buildings; in September, also in collaboration with Now & There, he led a parade that included local performers from the South End to Upham’s Corner with “Augment,” a puffy riot of deconstructed inflatable lawn ornaments — the Easter bunny, Uncle Sam, Santa’s reindeer — all twisted up in a colossal Frankenstein bouquet of childhood memories. Cave understands that the lost art of creating community, of joining forces to accomplish a task at hand, whether it’s beading a curtain or mending the tattered social fabric, depends upon igniting a kind of dreaming, a gameness, a childlike ability to imagine ideas into being. But it also involves recognizing the disparate histories that divide and bind us. The strength of any group depends on an awareness of its individuals.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/01/arts/design/nick-cave-chicago.html

Nick Cave even met his husband through a collaboration—he asked him to design his first book.

https://www.wmagazine.com/fashion/nick-cave-artist-soundsuits-retrospective-chicago

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/15/t-magazine/nick-cave-artist.html

The story, his words, the sentiments, the videos, the dancing, the energy. What a wonderful way to roll into Friday. Thank you for the introduction to Nick Cave, his art, his philosophy, his life!

It all began with the unquenchable delight of Sharron Cave, who could turn a handful of popcorn into a celebration. I love Nick Cave and I love Sharron. The magic he makes is a tribute to her.