Art Dogs is a monthly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, turtles, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these posts in your email inbox.

Good morning Art Dogs!

I hope your March went swimmingly. At the beginning of the month, I mentioned that I was going to move to a monthly cadence for posts so I can have some time to really invest into each one. This is the first of those monthly posts.

In between, I’ve been sharing shorter Art Dogsian stories and anecdotes on Notes, which I’ve found quite fun. Here are a few if you’re interested.

Note: On Flannery O’Conner’s peacocks: “My quest, whatever it was actually for, ended with peacocks. Instinct, not knowledge, led me to them.”

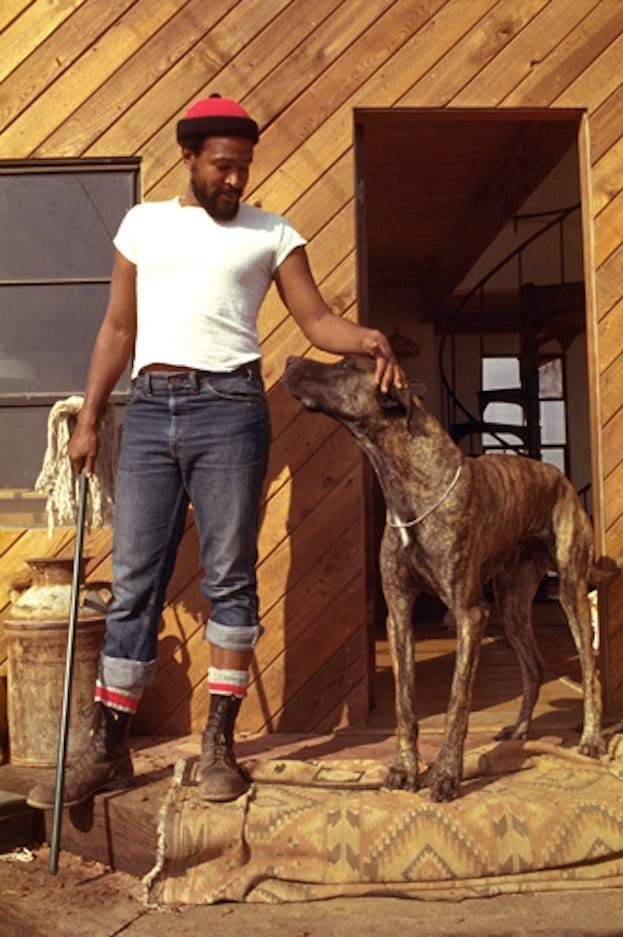

Note: On Marvin Gaye’s blissful years in Topanga Canyon with his dogs: “For weeks I’d just sit and stare into space. With enough time, I was sure this was the place where I could create my masterpiece.”

Note: On Richard Serra’s youth in the Outer Sunset (43rd and Taraval), two doors down from Mark di Suvero: Looking back, di Suvero, who turns 86 this month, recalled long, riotous afternoons when he and a young Mr. Serra played in the dunes, skidding down them on flat cardboard, having to empty their shoes of sand before their mothers let them back into the house. Their relationship, however, was not completely harmonious. “Our dogs would fight,” di Suvero recalled with amusement. “I had a dog, they got a dog, and his father would say, ‘Let them fight!’”

Ok, onwards to Pat Highsmith! I hope you enjoy today’s story.

xo

Bailey

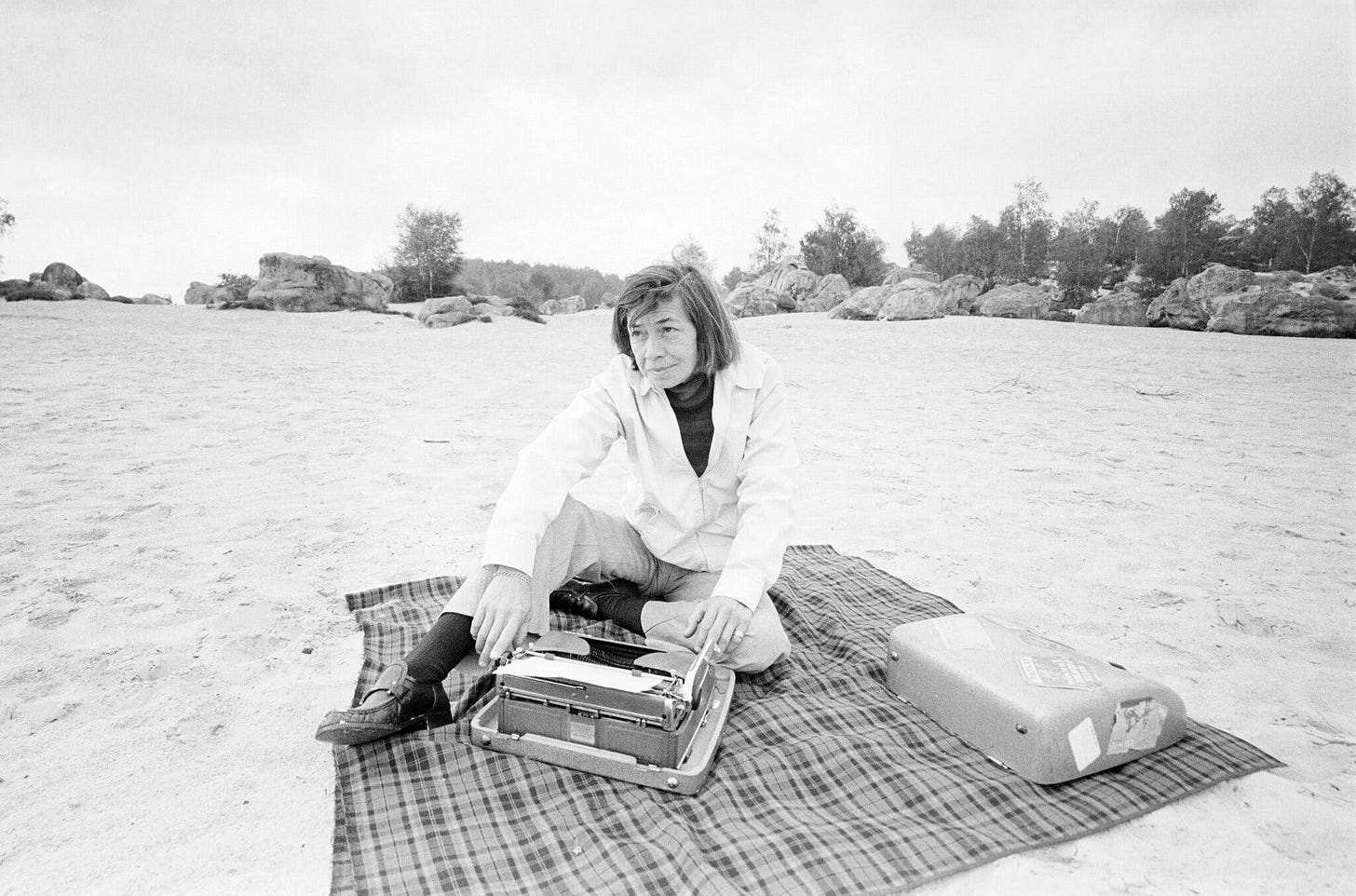

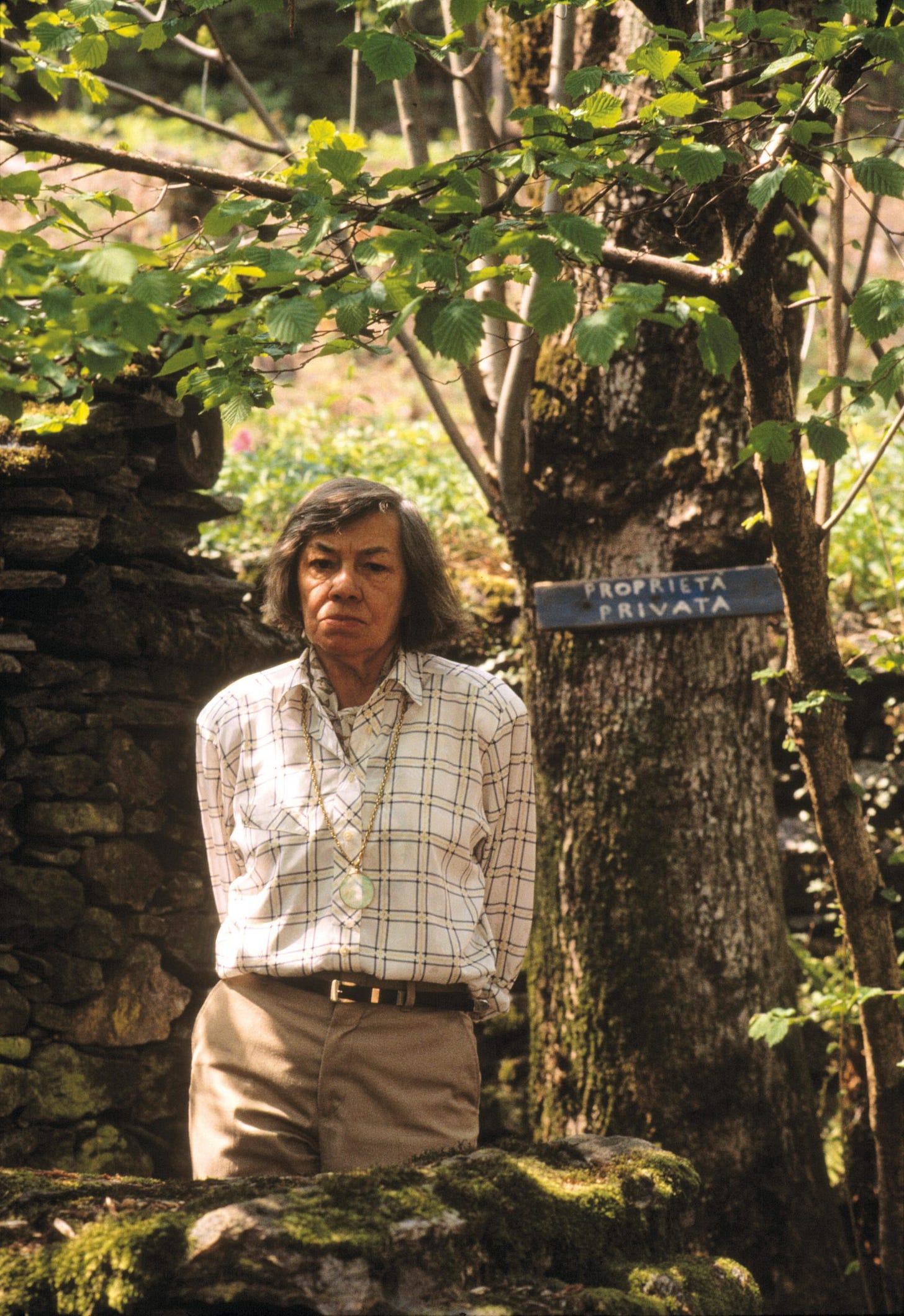

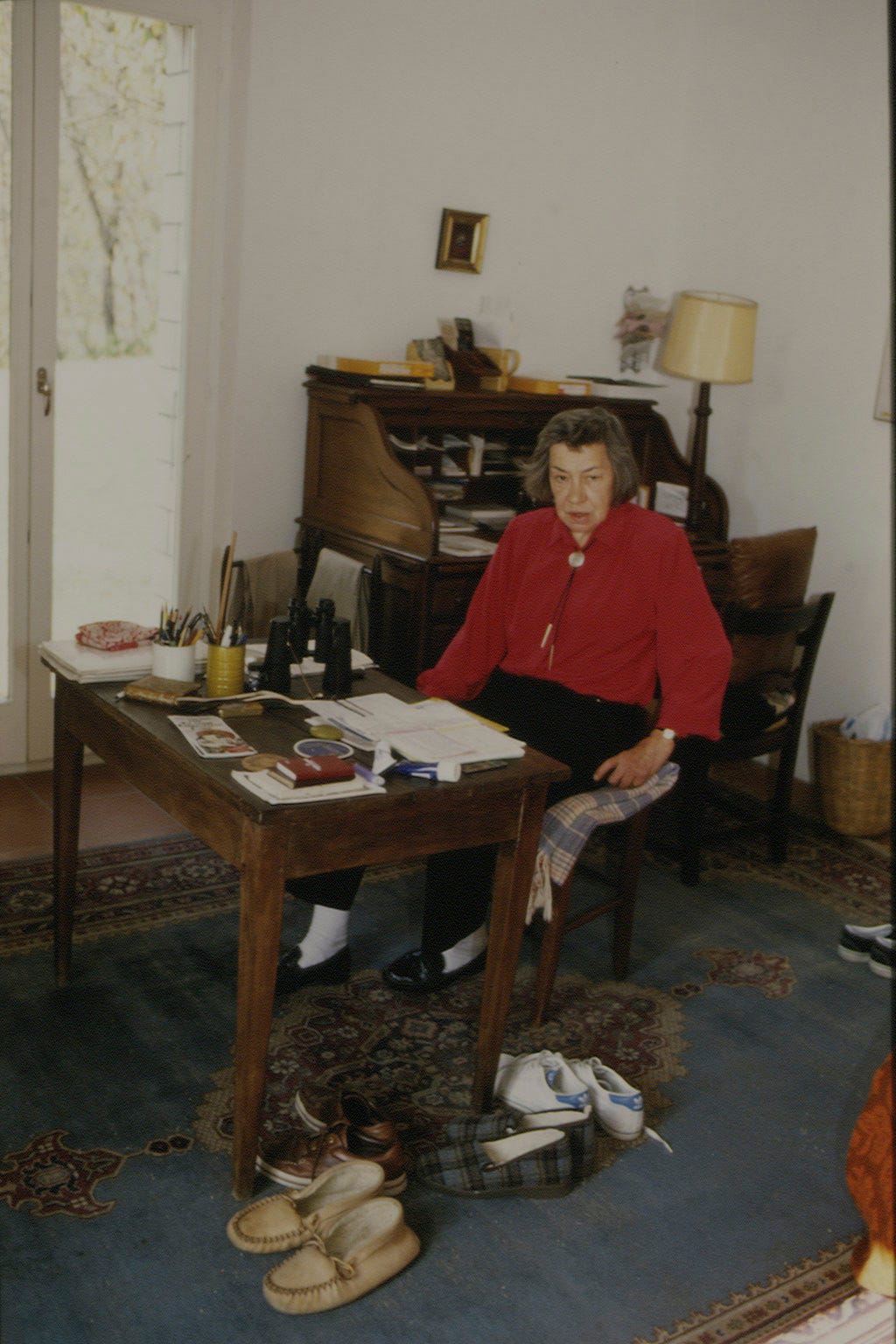

Patricia Highsmith has been called one of the greatest psychological thriller writers of all time and a master of “stealth, disquiet, menace.” Author Graham Greene described her as “the poet of apprehension” and her writing as “relentlessly objective, examining flawed people as she might curious insects.”

Patricia published 22 books and numerous short stories in over five decades. More than two dozen of her stories have been adapted to film. Her first novel, Strangers on a Train, was turned into a movie directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Her book The Price of Salt, published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan in 1952, was republished 38 years later as Carol under her own name and turned into a 2015 film. (It was the first lesbian novel with a "happy ending.") Her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley has been adapted on more than one occasion.

And by all accounts, Patricia Highsmith was a monster.

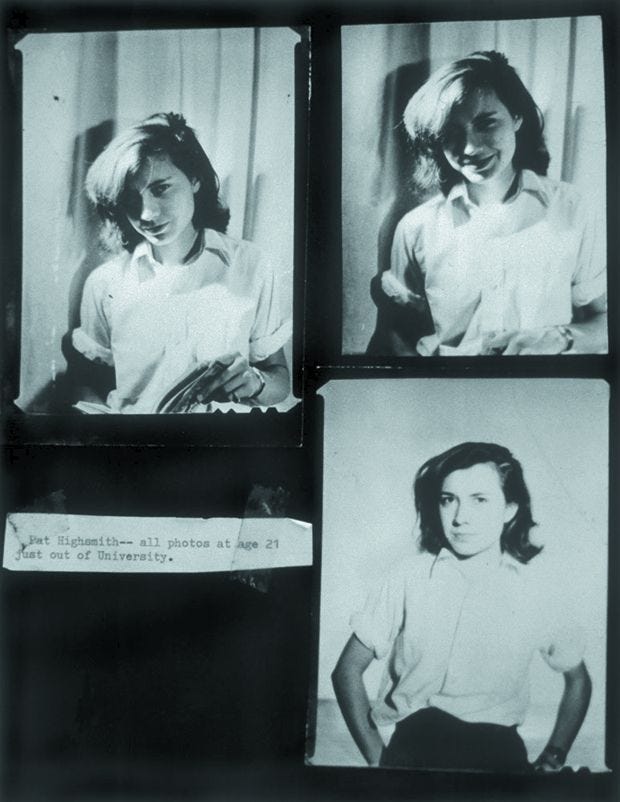

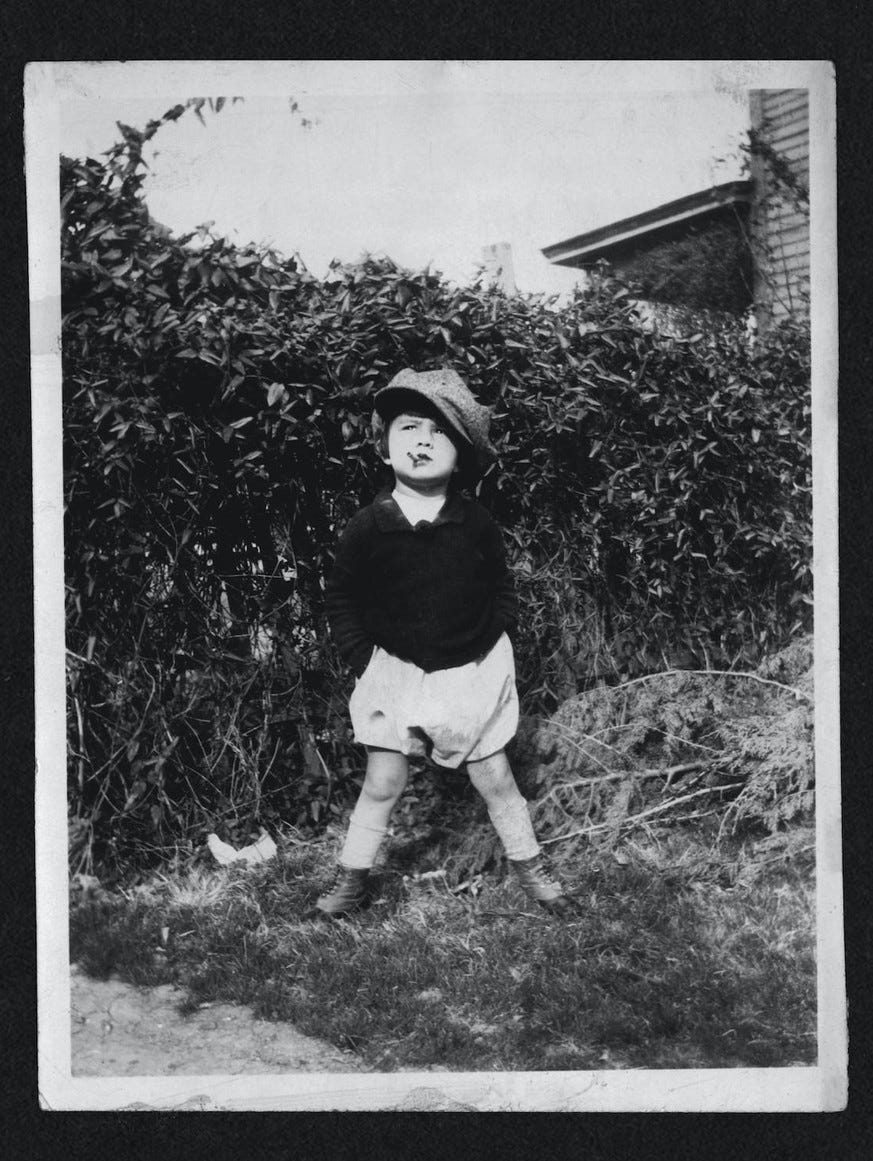

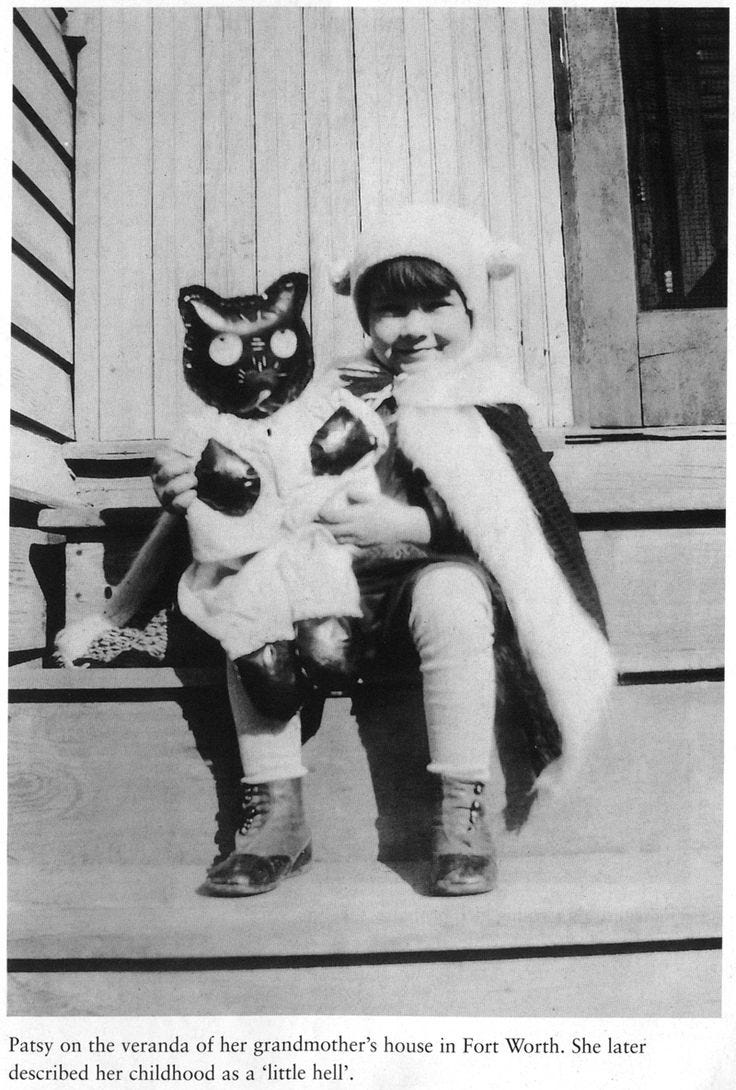

Patricia Highsmith was born Mary Patricia Plangman in Fort Worth, Texas in 1921. As is true for so many great writers, her childhood wasn’t a happy one.

Her parents, Jay and Mary, were both commercial artists. They divorced ten days before Patricia’s birth, and her mother once said that she had tried to abort the pregnancy by drinking turpentine.1 Patricia would not meet her biological father until her early teens.2 Soon after, she claimed that her father got out his pornography collection and “promptly tried to seduce her.”

As a six year old, Patricia followed her mom and new stepfather to New York. The couple’s finances were tight, and they fought often. Patricia was sent back to Texas to live with her grandmother for a year. She felt abandoned by her mother and said it was the "saddest year" of her life. Fortunately, her grandmother had taught her to read at just two years old, and Patricia spent her time in Texas exploring her grandmother's extensive library.3 She later said that she has been “writing the same sort of thing since I was 15 years old —about people who are a little cracked. I saw a lot around me.”4

By the age of 12, Patricia had decided she was a man born in a woman’s body. Her analyst eventually suggested that she join a therapy group of “married women who are latent homosexuals,” which she agreed to for six months in an attempt to “normalize” herself. Instead of taking the therapy seriously, however, Patricia opted to romance other members of the group, which she documented in her diary in her diary. (“Perhaps I shall amuse myself by seducing a couple of them.”)

She enrolled at Barnard College in the late 1930s, where she studied English composition, playwriting, and short story prose. For one year, she also studied zoology and “felt a strong tenderness for animals, particularly cats and snails, both of which she kept as pets.”5 We’ll get to that later.

While in college, she started what would become a lifelong alcohol habit6 and visited lesbian bars throughout the city, developing a reputation as a womanizer and “a sapphic Dennis the Menace.”7 “I repeat the pattern, of course, of my mother’s semi-rejection of me,” she once wrote. “I never got over it. Thus I seek out women who will hurt me in a similar manner.”

At just 19 years old, her short story “The Heroine” was published in Harper's Bazaar. It was selected as one of the twenty best stories that appeared in American magazines in 1945 and won the O Henry award for short stories in 1946. Still, when she applied for work at major publications such as Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, Mademoiselle, Good Housekeeping, Time, Fortune, and The New Yorker, she couldn’t get a position. Fortunately, Truman Capote and an editor at Harper's Bazaar, where she had published “The Heroine,” put in a word for Patricia to get into a foundation for the arts called Yaddo8 in New York. Alongside Flannery O’Conner (whom she detested), Chester Himes, and other artists, she wrote her first book. It was met with six rejections, but a rewritten version of the book about two men who exchange murders was accepted on the first try.9 Alfred Hitchcock later turned this book into “Strangers on a Train.”

At 28, Patricia's career was underway.

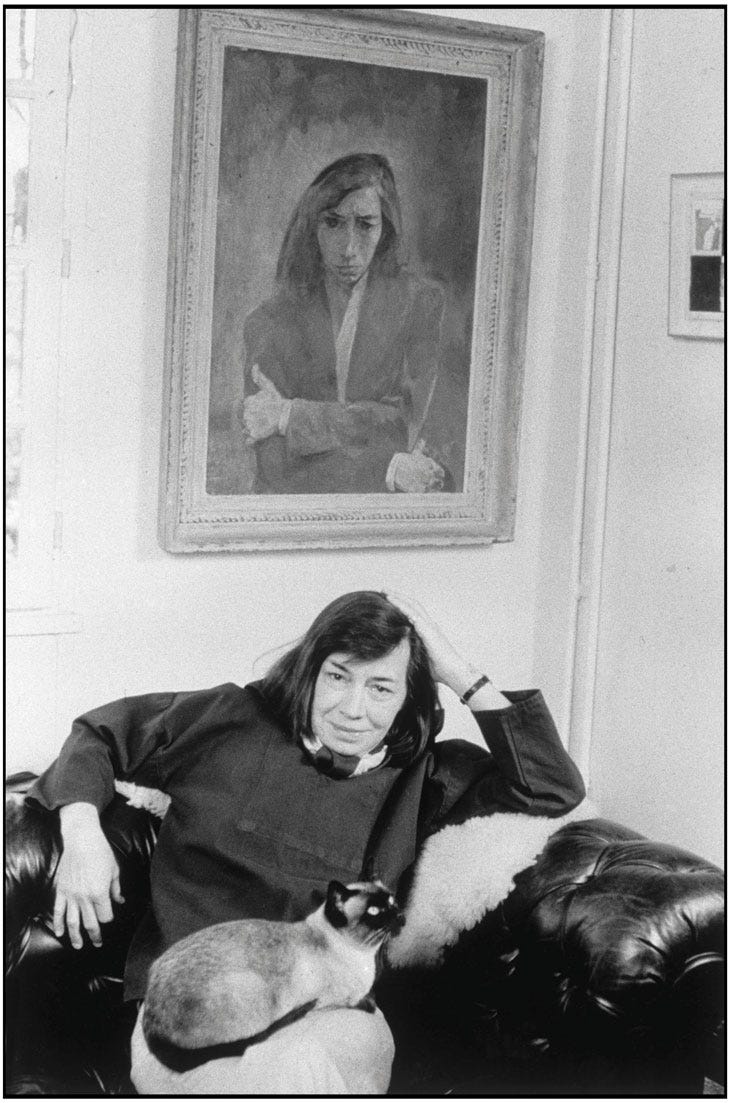

By all accounts, Patricia Highsmith was an unlikeable adult, her private life a “fiasco—squalid, chaotic, often extraordinarily painful.” The 8,000+ diary pages she left us with reflect this transformation—the notes “scribbled by a dissipated tomboy who aged into a cantankerous dragon, are ribald, chaotic, and – as her prejudices calcify – often nasty.”10

She has been universally described as a raging alcoholic, a misanthrope, and even “next to impossible to be around.” She made horrific racist, anti-semitic, and misogynistic comments throughout her life. Her former publisher once said she was “mean, hard, cruel, unlovable” and the “most odious woman he's ever met.” Even her oldest friends called her “hormonally strange” and “a woman at the mercy of her emotional tides, drawn to the darkest corners of her psyche.”11 Some believe she may have fit the classic definition of a sociopath.12

Of all that I’ve read about her demeanor, I found this passage by Terry Castle the most enlightening:

[Patricia Highsmith] had excruciating difficulties engaging with other people. Virtually everyone who met her remembers her lifelong diffidence: her pathological fear of shaking hands, the way she would reflexively take several steps backward when introduced to someone, the hostile and ruinous drinking. Some readers will disparage [her biographer’s] revelations as sordid and unwelcome, like photographs of a car wreck, but to do so is also to miss the point. Quite as much as T.E. Lawrence, Highsmith was a Prince of our Disorder (though she was far more mannish than he). Anyone who has grown up troubled or shy or gay will instantly identify with certain parts of her story--the towering rage above all. However cruelly and ignobly she vented it, her animus toward the world was a psychic necessity, a survival mechanism. In contemplating Highsmith's life and work, Terence's attitude is the right one: Humani nil a me alienum puto. [“I am human: I consider nothing human is alien to me”]

But the fiasco of the life is also the key to the work. Highsmith's personality disorder is everywhere on display in her novels--most strikingly in her plots, which like those of her masters Dostoevsky and Camus (or of J.M. Coetzee) turn upon the unbridgeable alienation of one person from another. Susannah Clapp once described Highsmith as "a balladeer of stalking." "The fixation of one person on another," Clapp observed, "oscillating between attraction and antagonism, figures in almost every Highsmith tale." This seems sadly apt. The stalker wants to get as close as possible to someone: close enough to see, hear, touch, taste, breathe (or murder) the other person, but without any real intimacy being established. Stalking is a parody of intimacy: a way of being in proximity without the pain--or the ecstasy--of actual attachment.

Over and over in Patricia Highsmith’s stories, one character develops a deadly obsession with another. “Obsessions are the only things that matter,” she once said. “Perversion interests me most and is my guiding darkness”

Fortunately for Grade A-sociopaths like Patricia Highsmith, we’ve got pets on this earth—animals that both horrible and wonderful humans can obsess over with little to no damaging consequences.

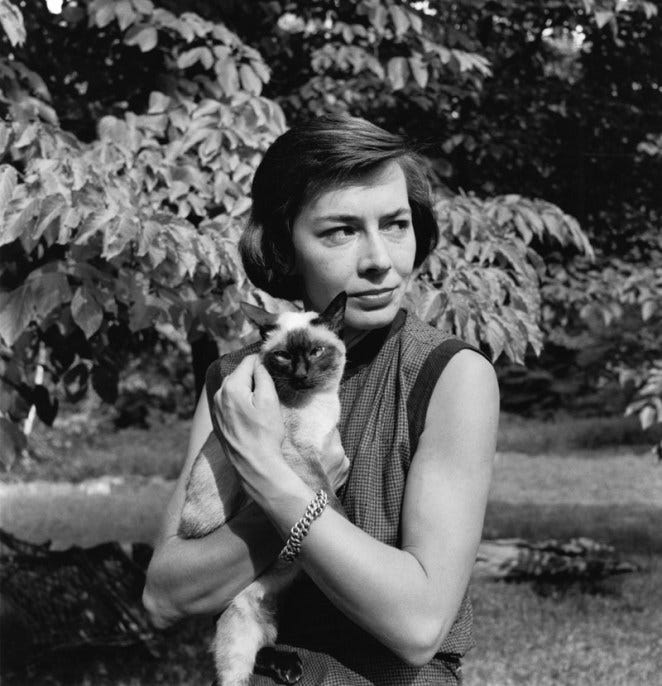

I mean, this cat looks in pure sun-soaked bliss.

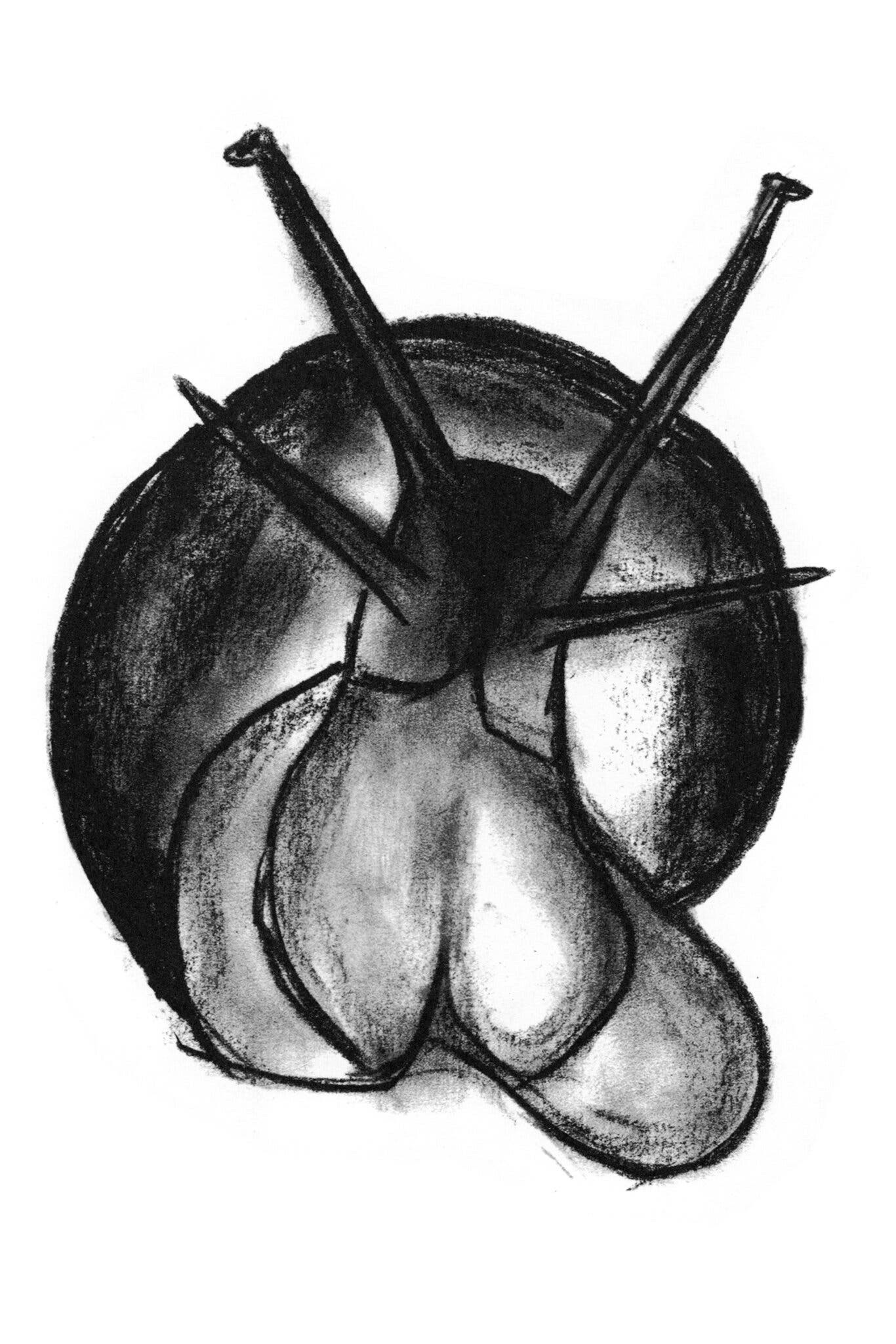

Patricia Highsmith never had a long term partner. Her many love affairs never lasted in part, as Gerald Lively writes, because of the author’s unpleasant personality. So she spent most of her time alone with her cats and…hundreds of pet snails. Her self-described “strange pastime” was observing and writing about the mating rituals of snails, which are nearly all hermaphroditic.

Patricia was first drawn to snails in 1946, before her career took off. While walking past a New York City fish market, she spotted “two snails locked in a loving embrace. Intrigued, she took them home, placed them in a fishbowl and watched their wriggling copulation, spellbound.”13 Eventually, Patricia would accrue up to 300 snails in the back garden of her home in Suffolk, England. Freaky pets for a freaky person! Rennie McDougall wrote:

As was typical of Highsmith, she was riveted by what others found repulsive or nauseating. “They give me a sort of tranquility,” she said of the gastropods. “It is quite impossible to tell which is the male and which is the female, because their behavior and appearance are exactly the same,” she wrote elsewhere.

Patricia took the snails with her when she left the house. “She traveled with snails in her luggage,” recalled

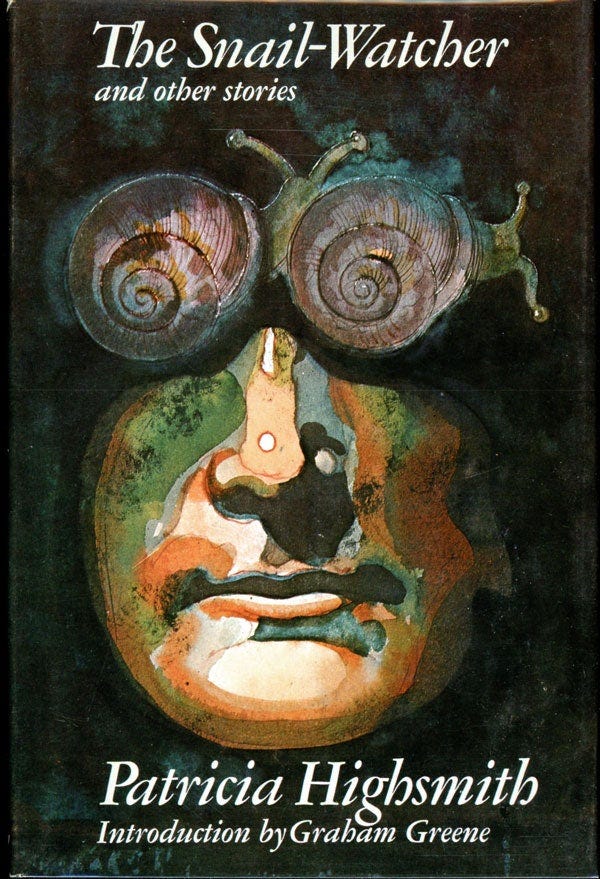

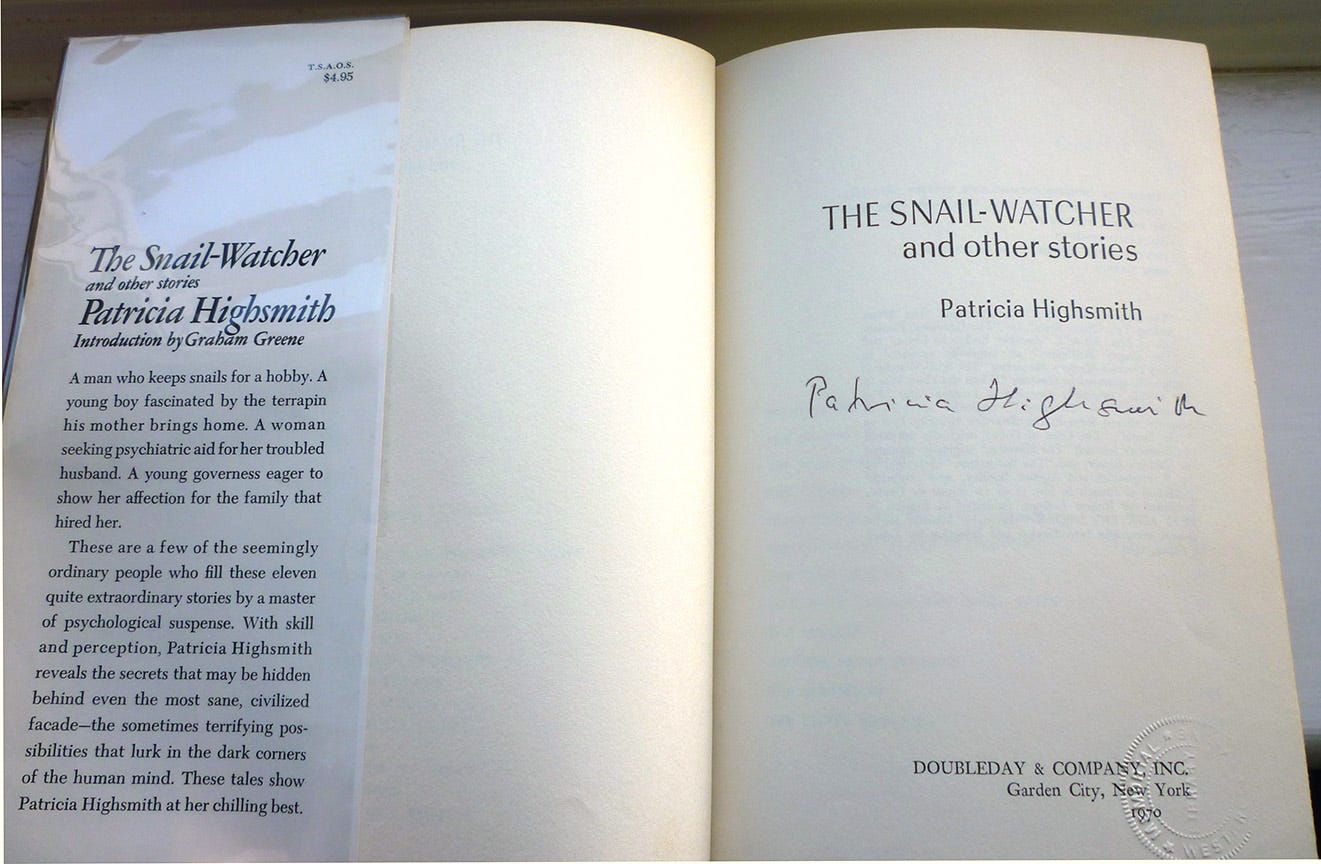

, usually taking five or six of “her favorites” with her when she went on holiday. Jeanette Winterson also saw her bring snails along to social events. “If she was bored at dinner parties, she might get a few snails out of her purse and let them loose on the tablecloth.”14 When Patricia moved to France, she had to illegally smuggle her snails from England into the country in batches. Former editor Larry Ashmead remembered her “sneaking them in under her breasts. She said that she would take six to ten of the creatures under each breast every time she went. And she wasn’t joking — she was very serious.”Snails even “slithered into her fiction.” In a short story called “The Snail-Watcher,” a snail enthusiast is smothered and consumed by the snails he keeps with him at home. “He swallowed a snail,” Patricia wrote. “Choking, he widened his mouth for air and felt a snail crawl over his lips onto his tongue. He was in hell!” Patricia’s agent deemed the story “too repellent to show editors,” but the story embodied the author in her “gruesome element” and made its way to publish.15

“Obsessions are the only things that matter. Perversion interests me most and is my guiding darkness” — Patricia Highsmith

Hesperios notes that in her diary, Patricia “wondered at the aplomb with which her snails slithered along the edges of razor blades,” and expressed curiosity about Søren Kierkegaard’s account of “the tightrope-treading anxiety with which we advance through life.”

Those of us (all of us?) with anxious and obsessive minds teeter on a razor blade. But while snails can bear the tension, we humans chase reprieve. We seek out our own philosophical or spiritual answers to the question: How do we assuage the turmoil of our psychic lives?

Kierkegaard described his approach to soothing anxieties as taking “a leap of faith” into the unknown. According to the Danish philosopher, faith does not possess logic, reason, or rationality. When a person accesses faith, Kierkegaard believes that person is demonstrating trust in something without using logic or reason. He’s saying there’s something transcendent, something higher, we tap into to drive ourselves forward.

I think Patricia Highsmith lost her ability to access Kierkegaard’s faith as a young girl. Thus she sought another tack—a radical one. “She challenged God by asking: ‘Have you the courage to show me hell?’”16 At just 26 years old, Patricia Highsmith wrote “My New Year's Toast” in her diary. It reads:

To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envies, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace.

The young author, void of Kierkegaard’s faith, veered instead into darkness. The resulting life was one of isolation, perversion, manipulation and… great art. The depth of Patricia Highsmith’s psychic strangeness fuels the stories, novels, and movies she created that continue to entertain us.

I suppose we need both the Kierkegaards and the Highsmiths making culture—thinkers and artists approaching life from the philosophical extremes so that we, their audience, may sample both sides of the razor blade and decide on our own approach.

Now it’s up to us. Will we dive into Kierkegaard’s faith or Highsmith’s perversion?

If you’re taking Highsmith’s path, please, do us all a favor. Get yourself some pets and a garden. It’ll take the edge off.

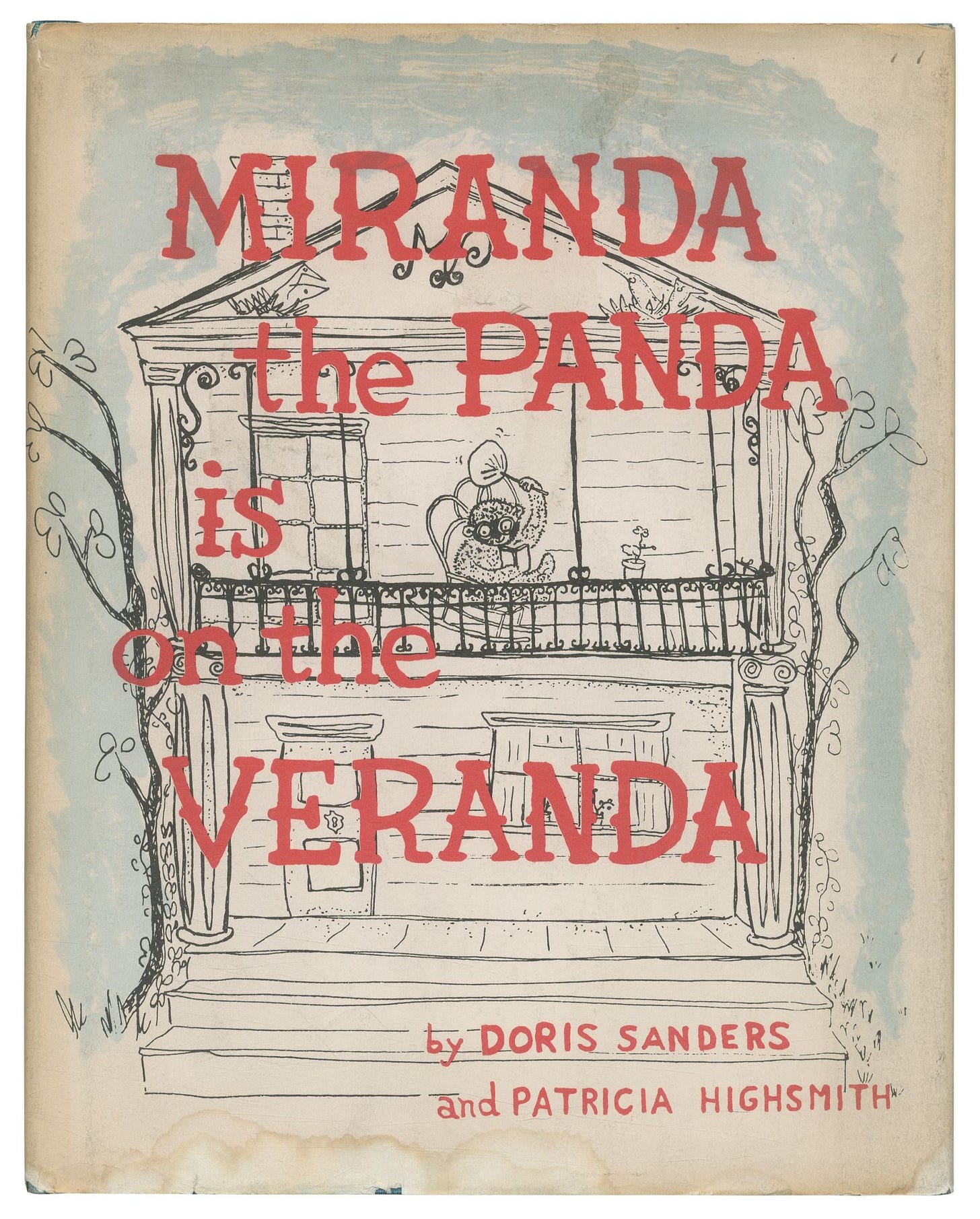

Bonus: Miranda the Panda is on the Veranda

If you need evidence that love (lust?) can bring us to our to knees, look no further than “Miranda the Panda is on the Veranda,” the children’s book avowed misanthrope and high-minded literary snob Patricia Highsmith created with a romantic partner.

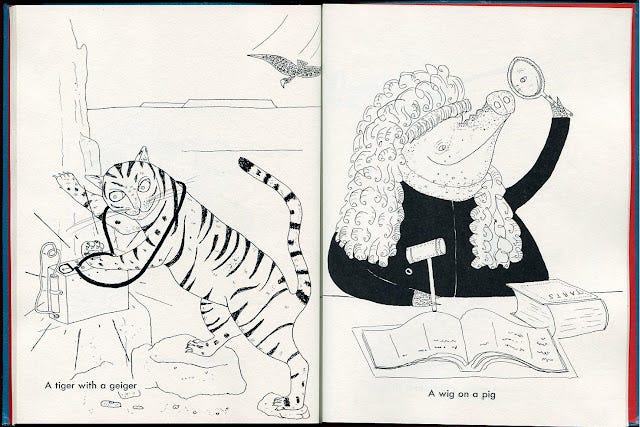

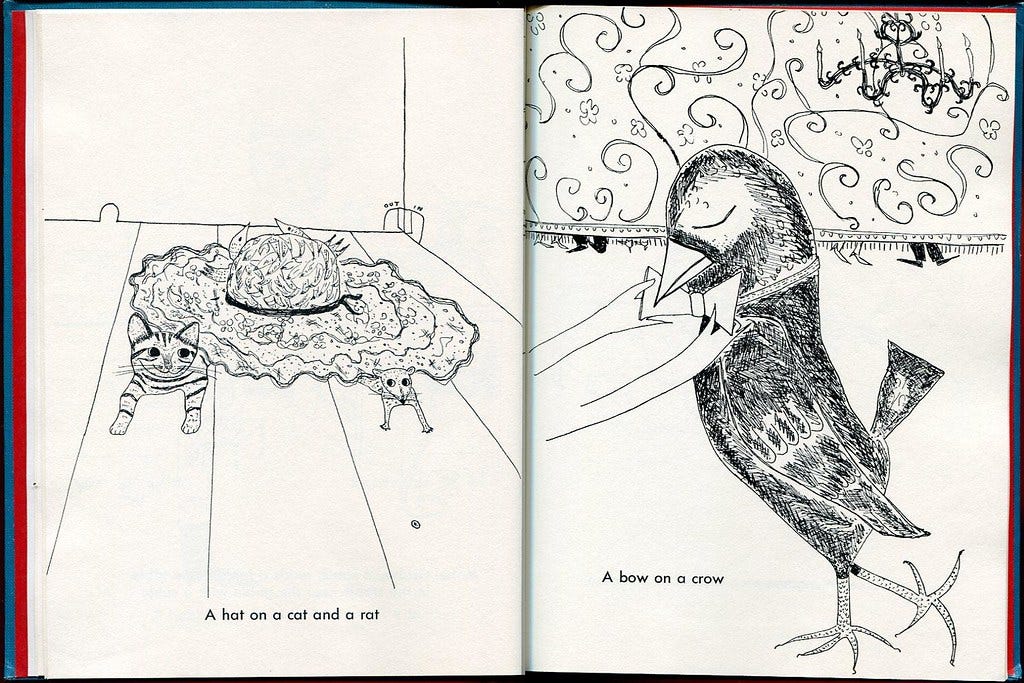

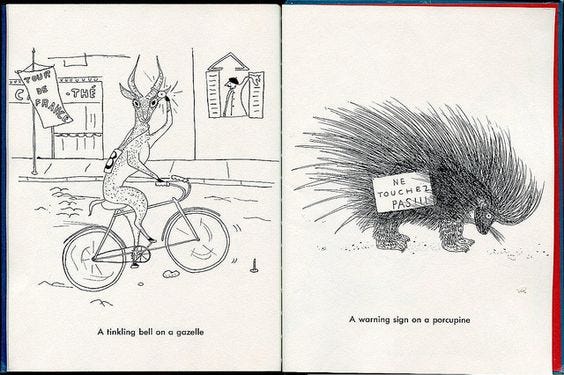

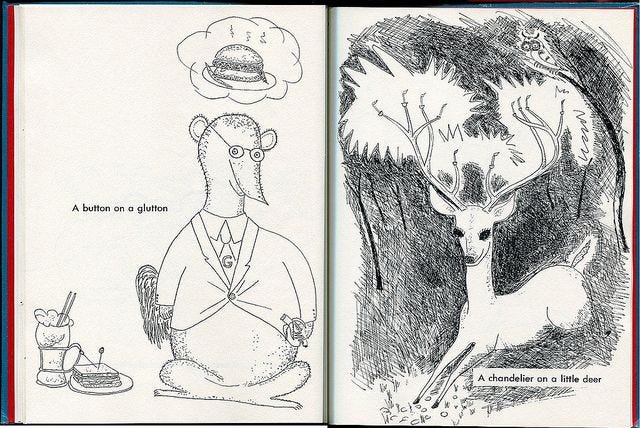

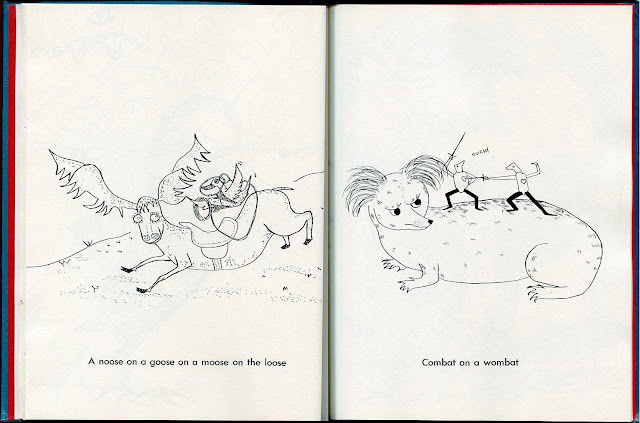

In 1955, the same year she published The Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia Highsmith began an affair with Doris Sanders, an advertising copywriter. Together they worked on the book, which Doris wrote and Patricia illustrated. It’s full of of simple nonsense rhymes (“Golf sox on a musk ox,” “A habit on a rabbit,” “A funny on a bunny,” “A chandelier on a little deer.”) It’s sweet-hearted and simple, and completely unlike anything else Patricia produced.

The year after publishing the book, Patricia cheated on Doris, ending their relationship

Enjoy!

https://web.archive.org/web/20150922211303/http://www.newrepublic.com/article/the-ick-factor

https://archive.org/details/talentedmisshigh0000sche

https://imageamplified.com/the-relevant-queer-patricia-highsmith-writer-champion-of-serial-killer-antiheroes-lover-of-cats-owner-of-snails-born-january-19-1921-2/

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/08/17/style/IHT-patricia-highsmithalone-with-ripley.html

Andrew Wilson in his biography Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith

https://web.archive.org/web/20150922211303/http://www.newrepublic.com/article/the-ick-factor

The author stayed at the retreat only once for two months during this summer of 1948, but left her entire estate, worth about $3 million, to Yaddo when she died in 1995.

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/08/17/style/IHT-patricia-highsmithalone-with-ripley.html

https://hesperios.com/news/dailiness-no-7/

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/t-magazine/patricia-highsmith-talented-mr-ripley.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20170325023853/http://www.saratogaliving.com/featured/patricia-highsmith-yaddo-and-america

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/t-magazine/patricia-highsmith-talented-mr-ripley.html

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/contributors/highsmith

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/t-magazine/patricia-highsmith-talented-mr-ripley.html

https://hesperios.com/news/dailiness-no-7/

This fascinating post sent me back to Highsmith’s guidebook PLOTTING AND WRITING SUSPENSE FICTION, which is full of wisdom for writers of any kind of fiction. She pointedly mentions snails and shells. For instance: “Writers and painters have by nature little in the way of protective shells and try all their lives to revove what they have, since various buffetings and impressions are the material they need to work from.”

I look forward to your articles and get excited every time I see one post! They are always so rich with new learning for me and ultimately each one sends me down the rabbit hole to read and learn more about your featured figures. Thank you for what I can only assume is a mountainous amount of research and effort that goes into each creation!