Art Dogs is a monthly-ish dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these ~monthly posts to your email inbox.

I first encountered Ruth Asawa’s artwork in 2009. I was a recent college graduate with an art history degree, working as an unpaid intern at the SFMOMA Artists Gallery in Fort Mason. Each morning, I would bike from my small sublet in the Inner Sunset, winding through the hilly Presidio in the fog and rain to reach the gallery on the water. It was there that I learned from Maria Medua and Andrea Voinot about the Bay Area’s art elders. Two names and their stories became etched in my memory: Robert Ogata and Ruth Asawa, both Japanese-American artists, both lived through internment, both possessed stop-you-in-your-tracks talent.

At the time, Ruth was virtually unknown outside of Bay Area arts circles. She was also in her 80s and bedridden with lupus. Her children had been forced to sell artworks Ruth had been gifted by friends, such as Josef Albers, to pay for the round-the-clock care that their aging mother required.

Ironically, this need to sell her artworks to cover medical expenses is one of the reasons many of us know about Ruth Asawa today. Jonathan Laib, a specialist at Christie’s, became curious about the source of these special pieces by Josef Albers. Such ambitious Albers works weren’t typically found in personal collections, but were coming to his attention from this family alongside sweet-hearted notes from Albers to a woman named “Ruthie.”1 At that time, Ruth Asawa’s last show with a gallery in New York was in 1958 and she had all but disappeared from the New York art world. Laib started looking into her work, setting in motion a rediscovery of Ruth’s art and story by the art establishment.

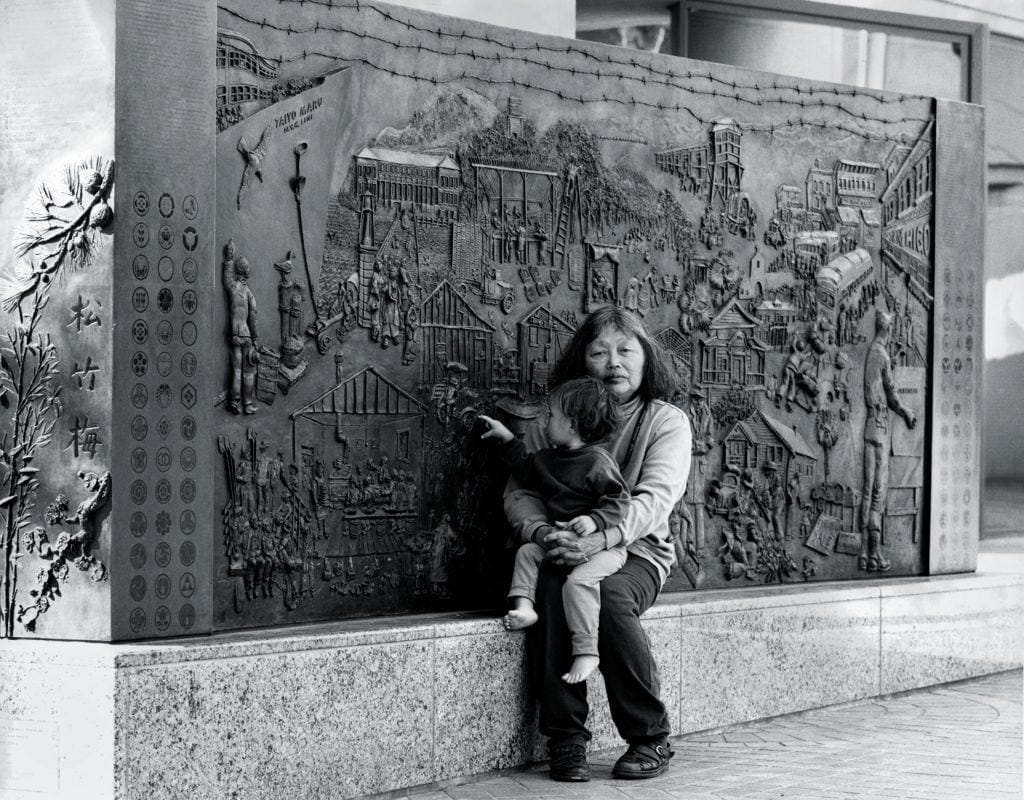

And Ruth Asawa has a truly incredible courageous story—one as epic as the art she was able to create. One that I think we all can take inspiration from in this exact moment, at least in America.

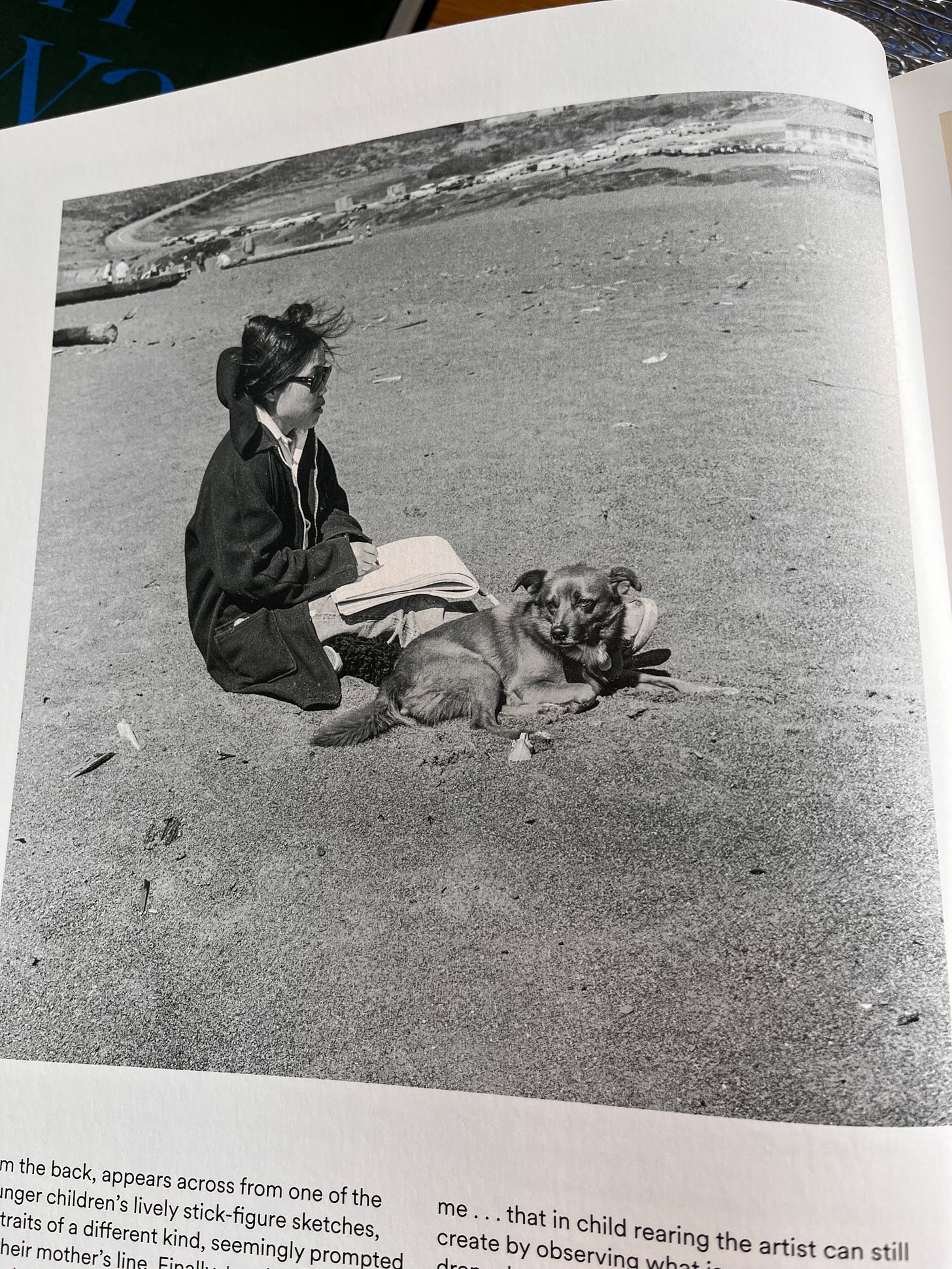

I’ve hesitated to write this Ruth Asawa post for months now. As a Bay Area native, her work and life mean so much to me. Could I write an essay that truly honors her…? I wasn’t confident the answer was yes. Then I re-encountered photos of her with her dog, Henry, in art books tucked away at the Whitney store just before the election results started rolling in. I decided it was finally time for Ruth Asawa’s beautiful life to have her Art Dogs moment. I hope you take as much inspiration from her as I have.

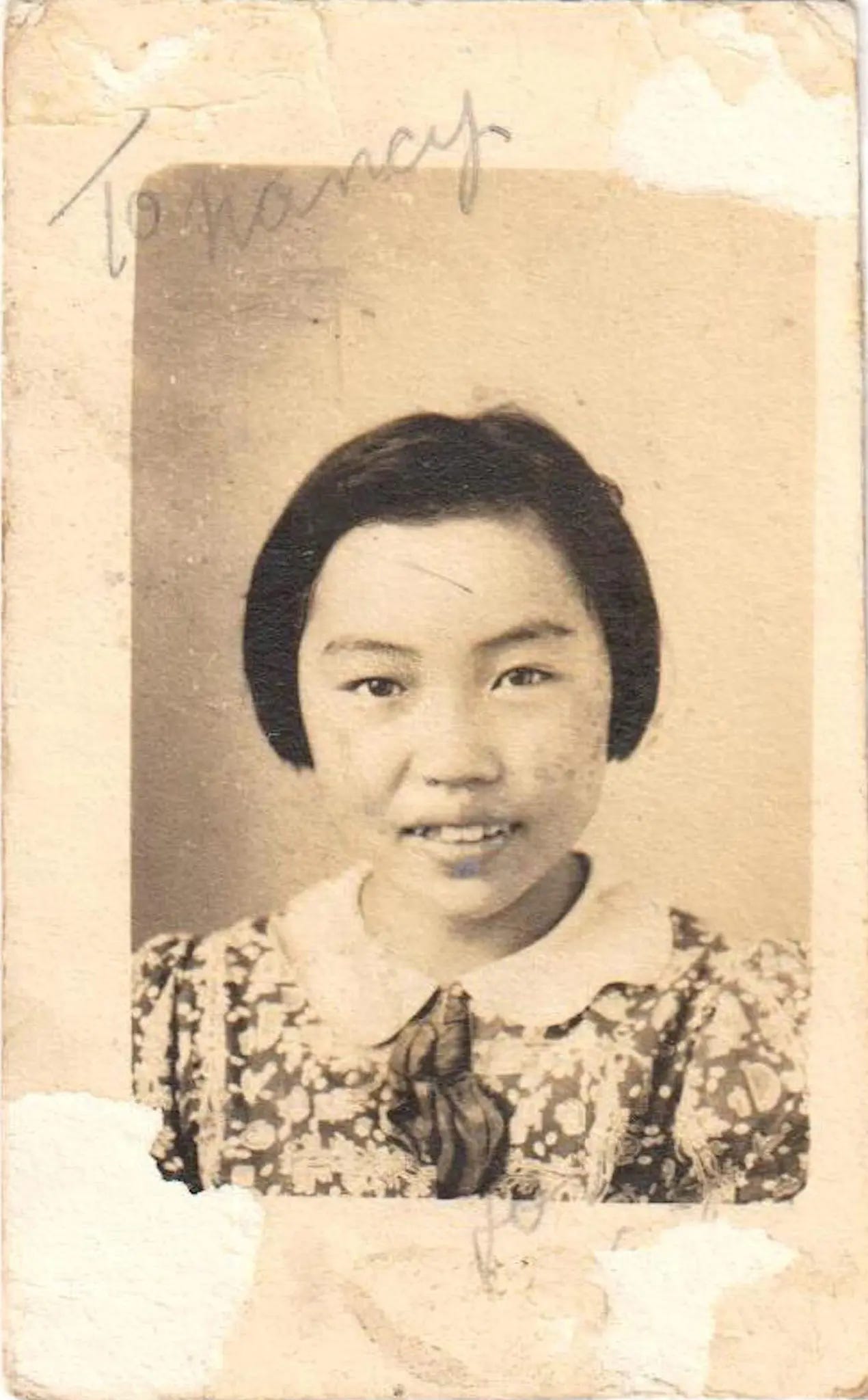

From her very first days until her very last, Ruth Aiko Asawa lived an astonishingly communal life. It began on her family farm in the 1920s, which she worked as a young girl with her parents and six siblings. Thessaly La Force excavated her early family life for The New York Times:

Her father, Umakichi, had worked as a tofu vendor, leaving Japan in 1902 to avoid conscription in the Russo-Japanese War. Her mother, Haru, was a Japanese picture bride — one of the thousands of Japanese women who, at the beginning of the last century, agreed, through the exchange of black-and-white portraits, to marry a Japanese man living in the United States in the hopes of a better life. By the time Ruth was born, the family was leasing an 80-acre farm in what would later become greater Los Angeles, unable to own property as immigrants because of the California Alien Land Law of 1913. Eventually, the Asawa family would grow to include seven children. Ruth was the fourth oldest.

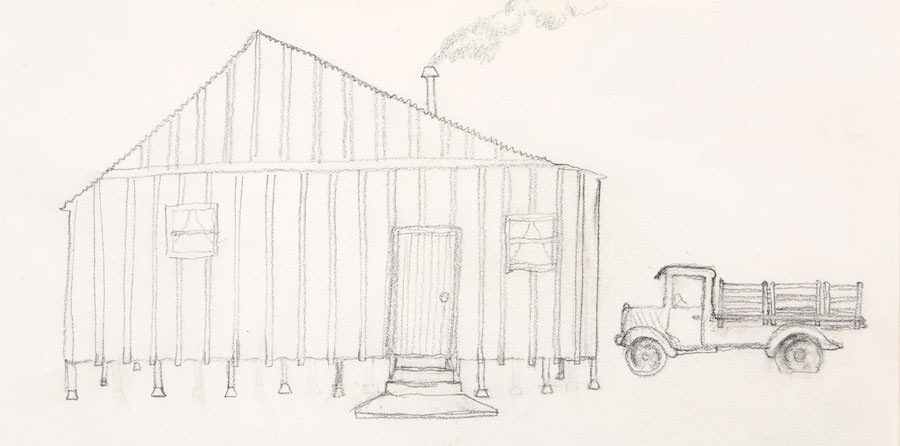

Life on the farm was tough and unsparing, with long days and little time for idleness. The family lived in a board-and-batten house, covered by a paper ceiling and a tin roof, that Umakichi built himself. Asawa’s mother…woke at around 3 a.m. each day to begin cooking the family’s rice; her father rose an hour later to check the gopher traps. Onions, broccoli and cauliflower were harvested every winter, strawberries every spring, and tomatoes and melons in the summer. They recycled the wooden crates down to the nails, which Umakichi would re-flatten with a hammer. “In my home we had virtually no materials,” Asawa said in a 1981 interview, “just a set of encyclopedia and a player piano. All the children wanted to play music but we didn’t have any money for lessons.”

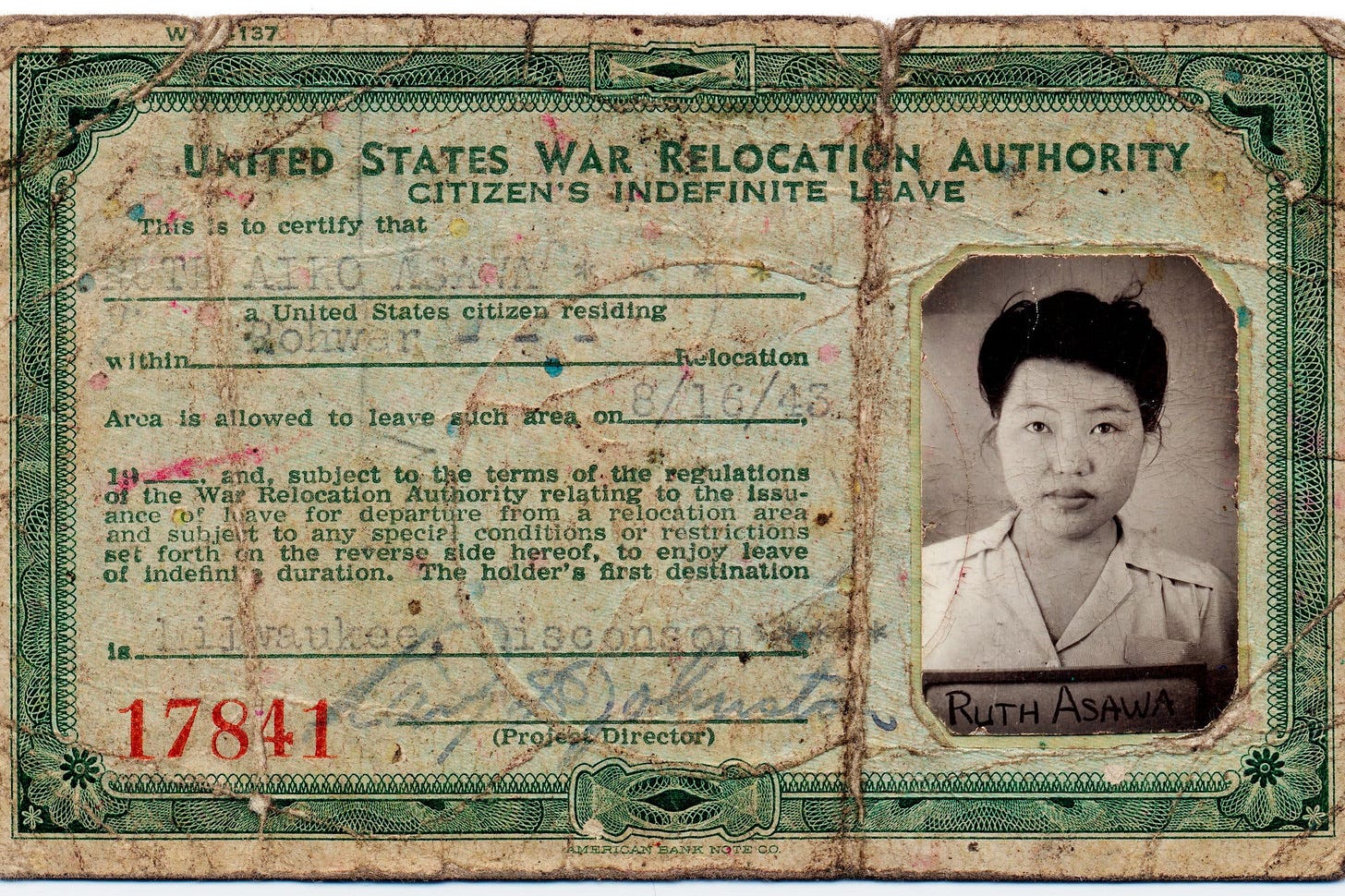

When Ruth was 15 years old, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. A few months later, Ruth’s father was arrested, and later she and her entire family were forced out of their home. “It was a Sunday, I guess, in February,” she recounted in an interview from the mid-1970s, “that we were working in the field and two FBI men came. They went and found my father in the field and marched him back into the house. He had lunch and then they took him away.” Ruth wouldn’t see her father again for six years. Soon after her father’s arrest, Ruth and her mother and siblings were taken to a detention center in Santa Anita. (Ruth later recalled having to say goodbye to the family's beloved horse Pim and watching the family dog chase behind the car as they left for Santa Anita Relocation Center.)

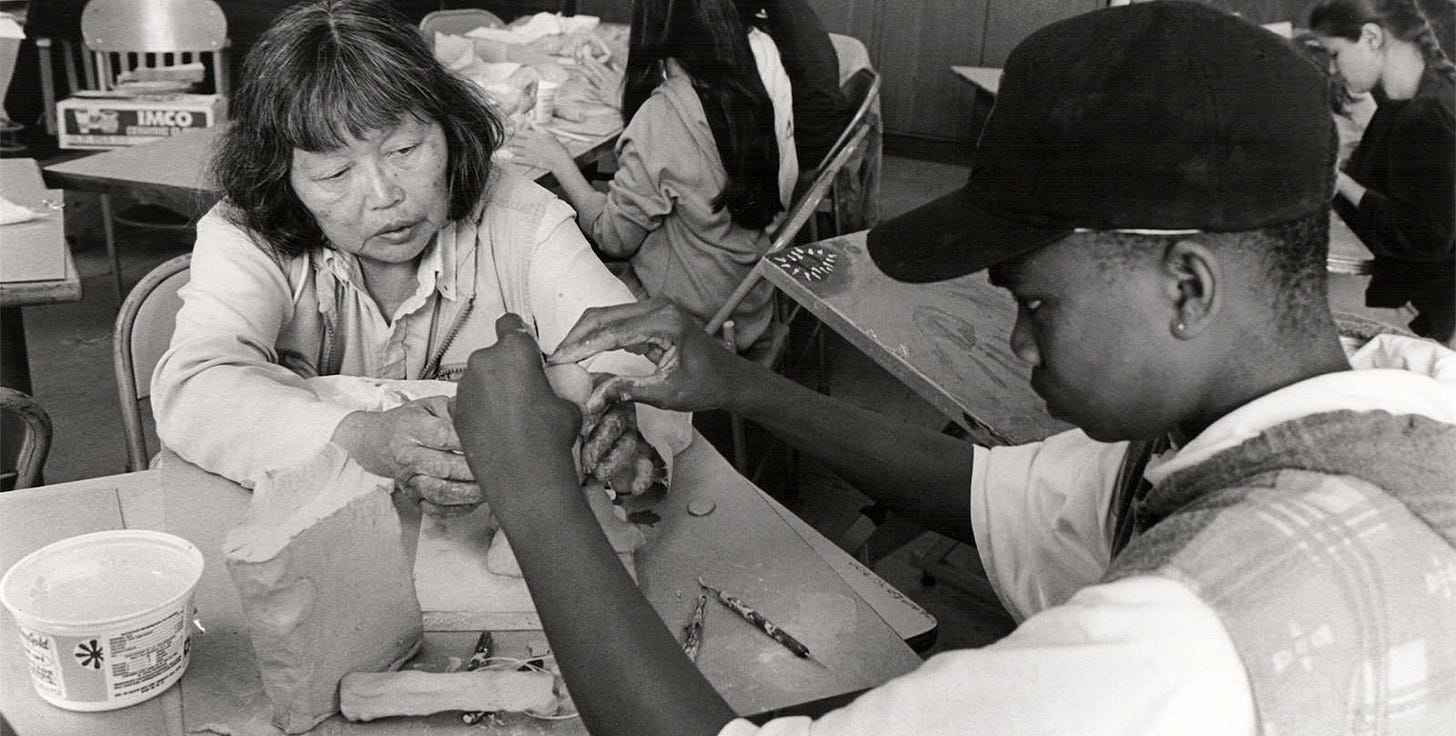

But a communal thread wove itself even through internment. It was there that Ruth had a life-changing experience with the generosity of fellow artists. Three Walt Disney artists who had worked on “Snow White” and “Pinocchio,” Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii and Ben Tanaka, were also detained at Santa Anita. They taught art classes to fellow detainees, guiding Ruth on how to draw on paper, charcoal and ink. She had more free time in the camp than on the family farm, and Ruth immersed herself in making art.

Looking at the way Ruth gave shape to the rest of her life, you can see how these communal seeds only continued to flourish as she aged.

After leaving the detention center, she went on to do what the Walt Disney artists had done for her: teach art. She enrolled at the Milwaukee State Teachers College, where her tuition was paid for by a Quaker scholarship.

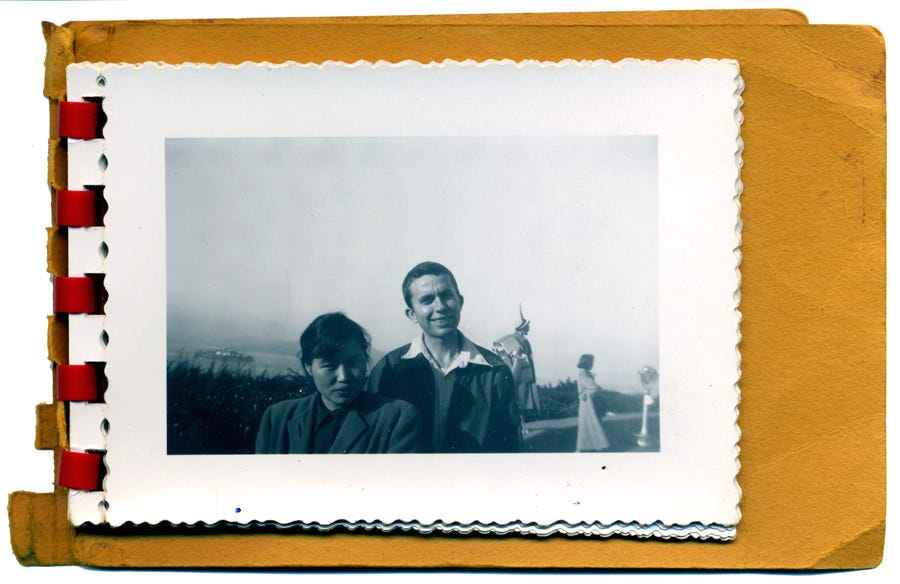

Because Ruth was Japanese-American, she was denied a teaching certificate, which prevented her from earning a living as a teacher, so she followed two of her friends to a summer course at a school called Black Mountain College, where she studied and created alongside a group of artists who would become the most consequential in American history. (Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Cy Twombly, and more.) Josef Albers, who had fled Hitler’s Germany with his wife Anni Albers, ran the art program and Ruth “blossomed under Albers’s tutelage…For the first time in her life, Asawa finally saw herself as an artist.”2

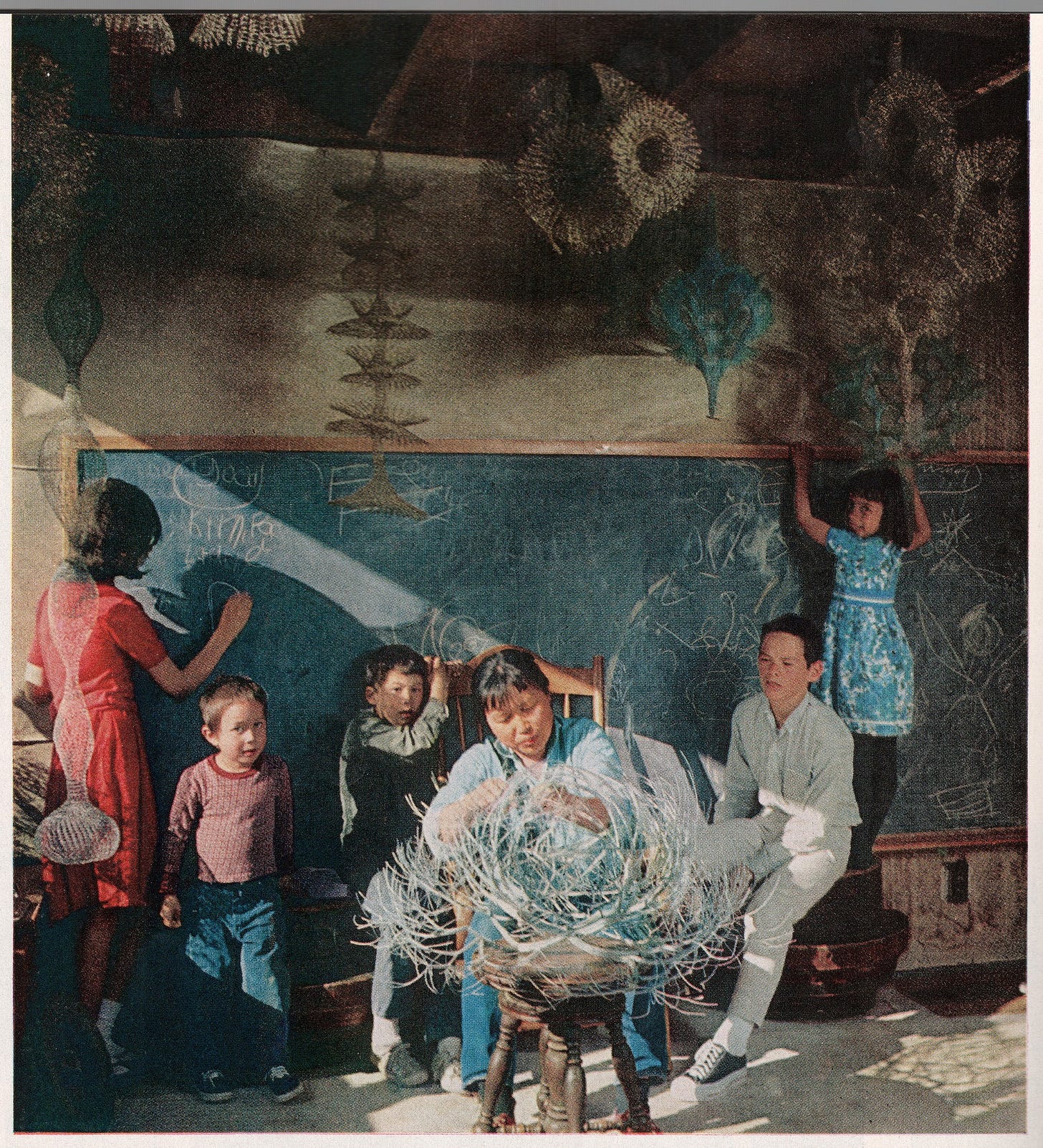

At Black Mountain College, Ruth met a young architect named Albert Lanier. Ruth married Albert, who was white, in 1949, when interracial marriage was still illegal in all but two states—California and Washington. They settled in San Francisco hoping it would be less hostile to their relationship. One year later, they had their first child, Xavier. Ruth and Albert would go on to have six children together. She refused to compartmentalize her life; Ruth’s family and artistic practices were interwoven, as you can see from the photographs of her studio and home.

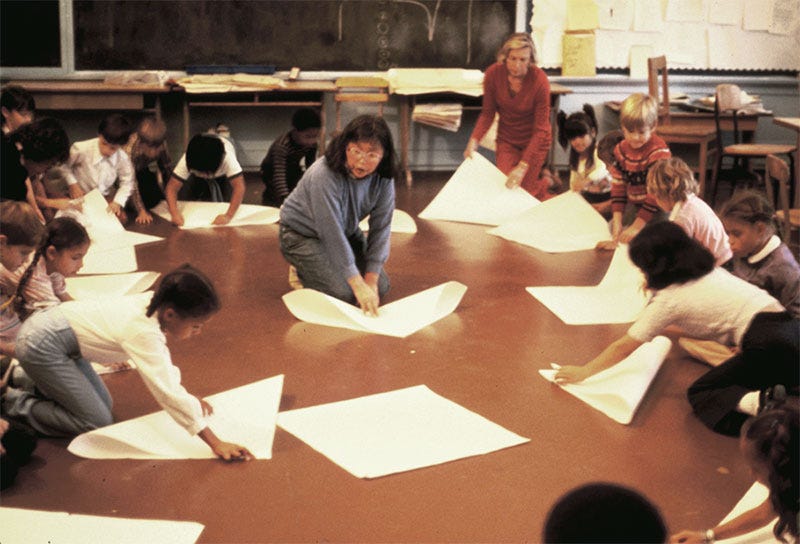

As her children entered school, Ruth became increasingly involved in local arts education. As writer Nancy Princenthal remarked, “During the years when the New York art world heard little of her, Asawa was very busy.” Instead of pushing the accelerator on her own career opportunities, she invested in others locally. She launched a volunteer-run art program in 1968, which had expanded to 40 schools by 1975. Later, she focused her energy on building a public high school for the arts in San Francisco. In 2010, the school was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts.

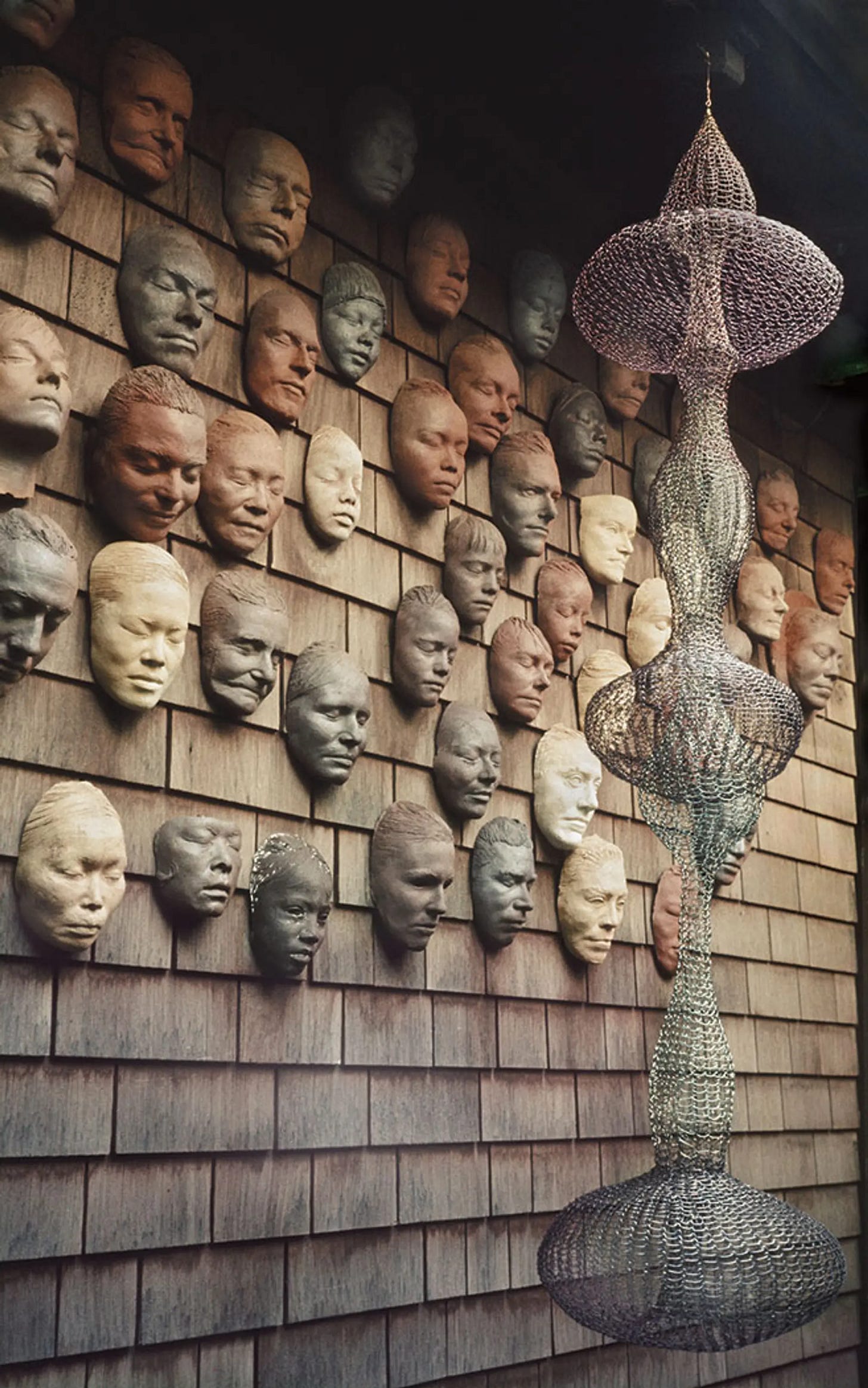

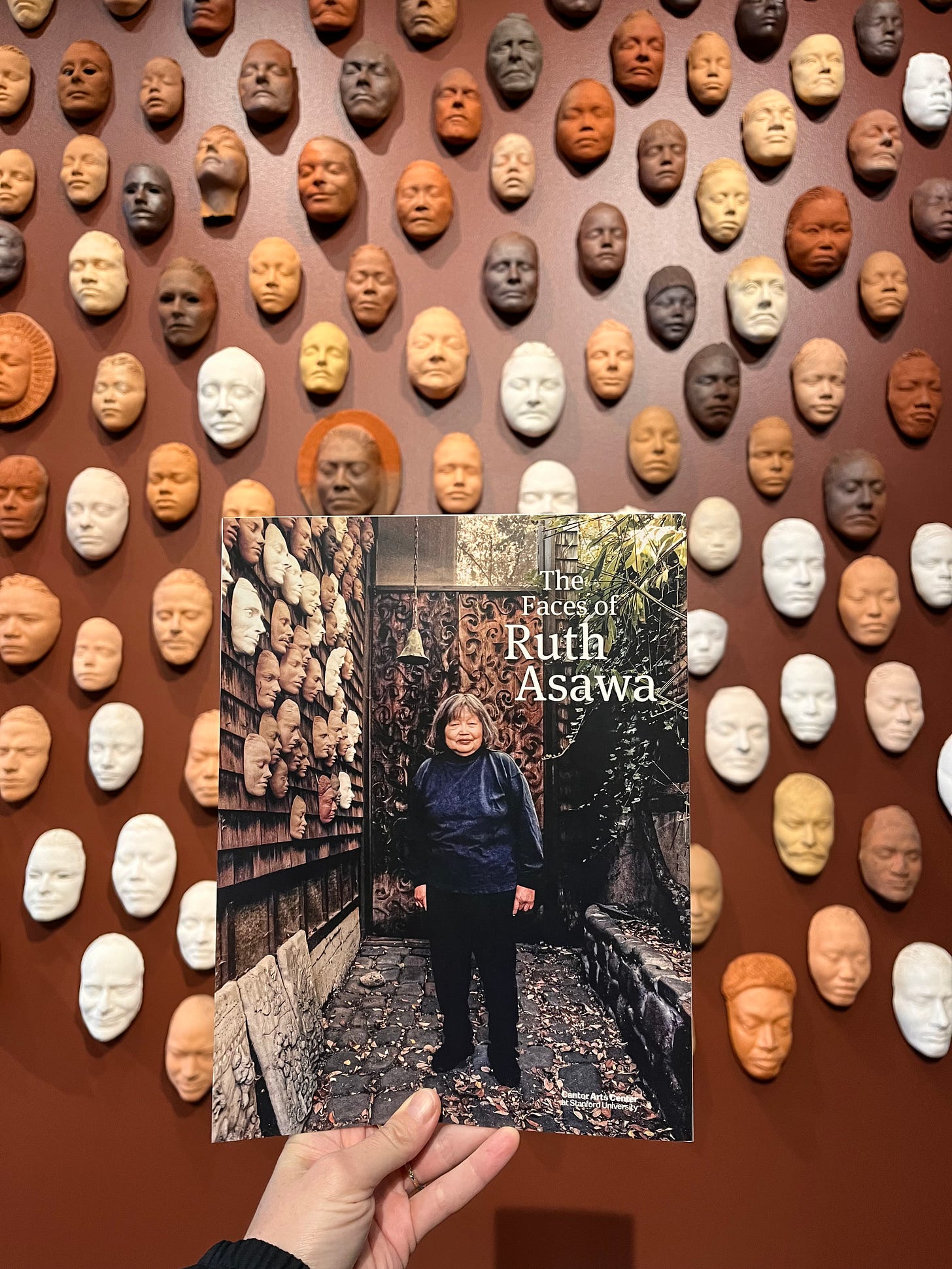

In 1966, Ruth started making mask artworks of her family and friends. She would make these pieces to document visitors to her home throughout the rest of her life, typically making two clay masks of each—one to give to the sitter and the other to hang on the shingled exterior wall of her Noe Valley house. By the time of her death in 2013, hundreds of masks hung clustered together on that wall. Ruth’s youngest daughter, Addie, said the mask-making was usually done at home with visitors on an impromptu basis. “It was very Japanese; she always gave people things she made, like plum jam, loquat chutney, pickles,” she says. “And then she would give you a mask, too.”3

Last year, I went to see these masks on display at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center.

Alongside the masks, the curators placed three pots made by Paul Lanier, Ruth’s son, that are on loan from the family.

Before Ruth died in 2013, one of her final requests was for her son, Paul, an accomplished ceramicist, to reunite her with her husband and son through his art. Paul mixed his mother’s, father’s, and brother Adam’s collective ashes with clay and threw a set of pots, one for each remaining sibling to keep. He fired the pots in an anagama, a traditional Japanese wood-fired kiln, over a seven-day period. As a result, the pots are exceptionally strong and “some of them had amazing colors,” he says, “like I’ve never seen before.”4 According to Ruth’s wishes, the pots were to “remain among the living—to be admired and even used to hold flowers from the family garden.”

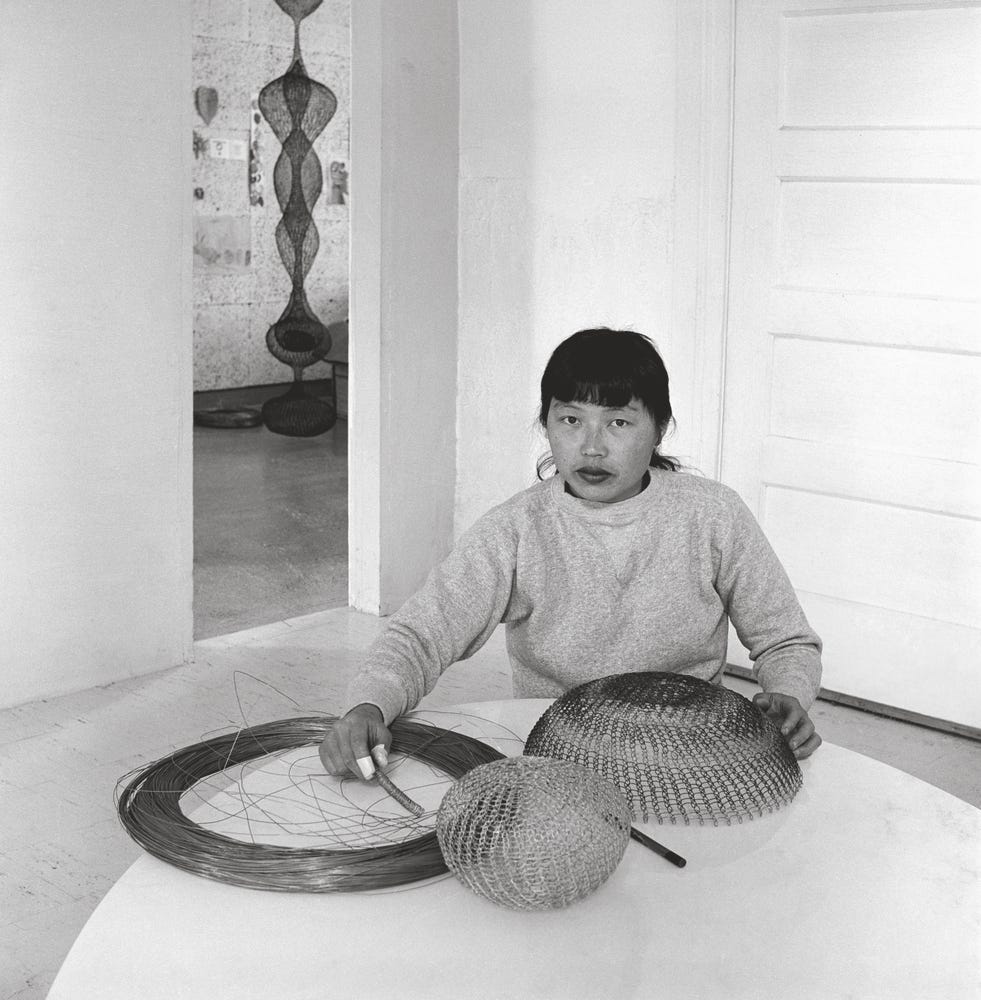

As an artist, Ruth Asawa devoted her hands to the act of transforming delicate, discrete strands of wire into transcendent unified works of art: sturdy in form, rigorously composed yet beautifully in balance.

Her communal life mirrored these interlocking sculptures. Author Marilyn Chase wrote that Ruth “fought arduously for the life she led,” deliberately constructing a “complex and vast” community around herself and her family. None of this emerged accidentally. Life taught Ruth that delicate threads, when connected in artful clusters, are what allow both people and forms to weather storms and the passage of time. She forged these bonds for herself as a young artist, and as she aged she devoted herself to weaving such webs for others.

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt wote that a public realm, where individuals come together to discuss, act, and share experiences, was essential for political life and human flourishing. Community for Arendt was not just a collection of individuals but a space where people engage with each other as equals, each contributing to the creation of a shared world. She viewed action and speech in the public sphere as the most meaningful forms of human activity, as they allow individuals to express their uniqueness while also creating a sense of shared identity.

Hannah Arendt was born 20 years before Ruth Asawa. There’s no evidence that they knew each other, but I wish Hannah Arendt could have witnessed Ruth’s life. I wish she had dined in her home, met her children, had her mask made and hung on the facade of Ruth’s Noe Valley home. If she had, Hannah Arendt would have borne witness to one of the most meaningful human lives as she described it—a truly communal life. From Ruth’s childhood on a farm to her generous teachers at the internment camps and Black Mountain College, to her robust friend group of peer artists, to her lifelong contribution to arts education, to her integration of her family life with her artistic practice, to her final resting place—every major chapter was communal. She forged so many of these spaces for herself and for others. What a wise woman. What an admirable life. May we all take inspiration from her in these tumultuous years to come.

Rest in peace, Ruth Asawa.

Bonus: Henry the dog

Many of the most beautiful photos you’ll see of Ruth in this post, both working and spending time with her family, were made by famed photographer Imogen Cunningham, one of Ruth’s best friends. Ruth met Imogen in 1950, around the time she had her first child, Xavier. Despite their 43-year age difference, they quickly developed a strong friendship “over their shared values, refusal to separate their artistic practices and family life, and love of plum jam.” And Imogen was responsible for a number of the photos we have of Henry the dog.

I wrote into Ruth’s family to learn more about Henry the dog. To my surprise, I received thoughtful responses from one of Ruth’s son’s, named… Henry! I hope you enjoy his answers.

Q: Were pets, animals in any way a part of Ruth's childhood?

Ruth grew up on a farm in Norwalk, CA, so she was surrounded by animals from an early age-- dogs, cats, chickens, horses, a donkey and pigs for slaughter (although only for a short time because the family found they did not like the pig slaughtering process or eating the meat). When she and her family were interned after the issuance of Executive Order 9066 in April 1942, Ruth recalled having to say goodbye to the family's beloved horse Pim and watching the family dog chase behind the car as they left for Santa Anita Relocation Center.

Q: I only know of one dog ("Henry”! Is your name related?) from family photographs later in life, but did the Asawa family have other pets?

I joke with my mother that I am named after Henry the dog (although that's yet to be officially confirmed or denied). In addition to Henry, whose full name is Henry Clyde Lanier (approximately 1964-1976), Ruth had a few cats as pets including Beasley (approximately 1970-1979) and later Fea and Ratty Bell (approximately late 1980s-1990s), neither of which were named by Ruth. In addition, my uncle Xavier had a monkey for a very short time that was a gift from a friend at school in approximately 1968.

Q: Can you tell me a bit more about Henry the dog?

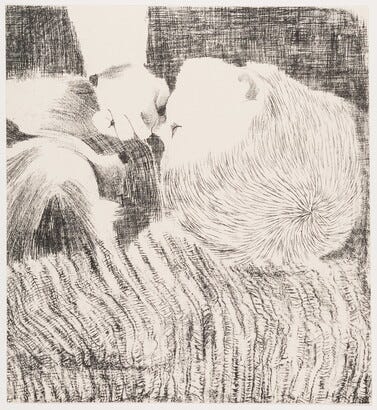

Henry the dog was technically my late uncle Adam's (1956-2003) and was around from roughly 1964 to 1976. He often accompanied the family to the beach and other outings, including to the family home in Guerneville, CA where he was originally from. My grandmother constantly drew the world around her including Henry who often slept/sat by her side. We are unsure of the origin of Henry's name, but my mother thinks it's likely that the family just thought it was a funny name for a dog.

Q: What did Henry the dog mean to Ruth? Can you describe their relationship, and how they spent time together?

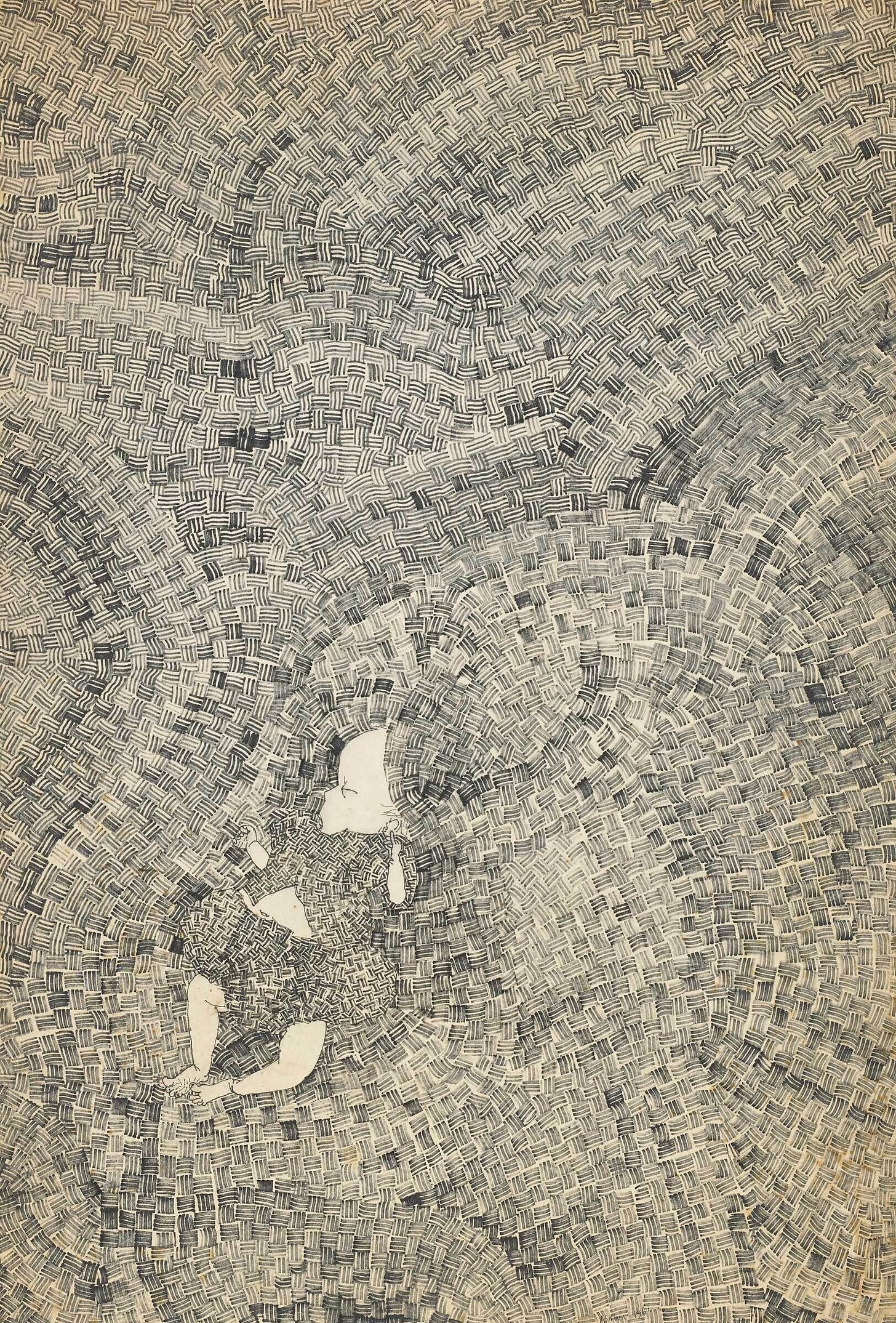

They spent a lot of time together and we have countless drawings and sketches of Henry in sketchbooks and on finished sheets, mostly of him sleeping. During Henry's final years he would cry when she left his side, so she'd have to pick him up and bring him with her when she moved around the house. Ruth often worked and drew at night while her family slept, so Henry would've been an ideal model late at night while all others were in bed.

Q: I know Ruth, Henry, and Imogen Cunningham would hang out a lot, it seems in nature. What was Imogen and Henry's relationship like - are there any notable anecdotes or stories?

We are unaware of any particulars about Imogen Cunningham and Henry's relationship. However, in our archives we have a Cunningham photo of Ruth sketching Henry at Fort Cronkhite in the Marin Headlands and the Asawa sketchbook featuring drawings of both Imogen and Henry drawn on the same day. Pretty cool!

There are countless drawings and sketches of Henry over the years along with a handful of drawings and watercolors of both Beasley and Ratty Bell, and a few sketches of Fea. Perhaps most interesting of the lot, however, is a drawing of a rocking chair with Xavier's sleeping monkey.

Thank you to

for inspiring this post! You should read her writing on Ruth Asawa here:Art Dogs is a monthly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, turtles, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these posts in your email inbox.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/20/t-magazine/ruth-asawa.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/20/t-magazine/ruth-asawa.html

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/07/05/ruth-asawa-made-hundreds-of-masks-of-her-san-francisco-communitynow-a-local-museum-is-putting-them-on-permanent-display

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/07/05/ruth-asawa-made-hundreds-of-masks-of-her-san-francisco-communitynow-a-local-museum-is-putting-them-on-permanent-display

Bailey, thank you for the happiness your writing delivered. I have long loved Ruth’s work. She is especially meaningful to me because i live in Black Mountain. Thank you for including the Black Mountain College connection.

I’m off to restack. in kinship, Katharine

What an inspiring artist and read. Thanks so much for writing and sharing this. It’s amazing that such a horrible thing as being forced into an internment camp had such an impactful silver lining for Ruth. (That bit reminded me that amidst the darkness, look for the light and I need reminders like that going forward…)