Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

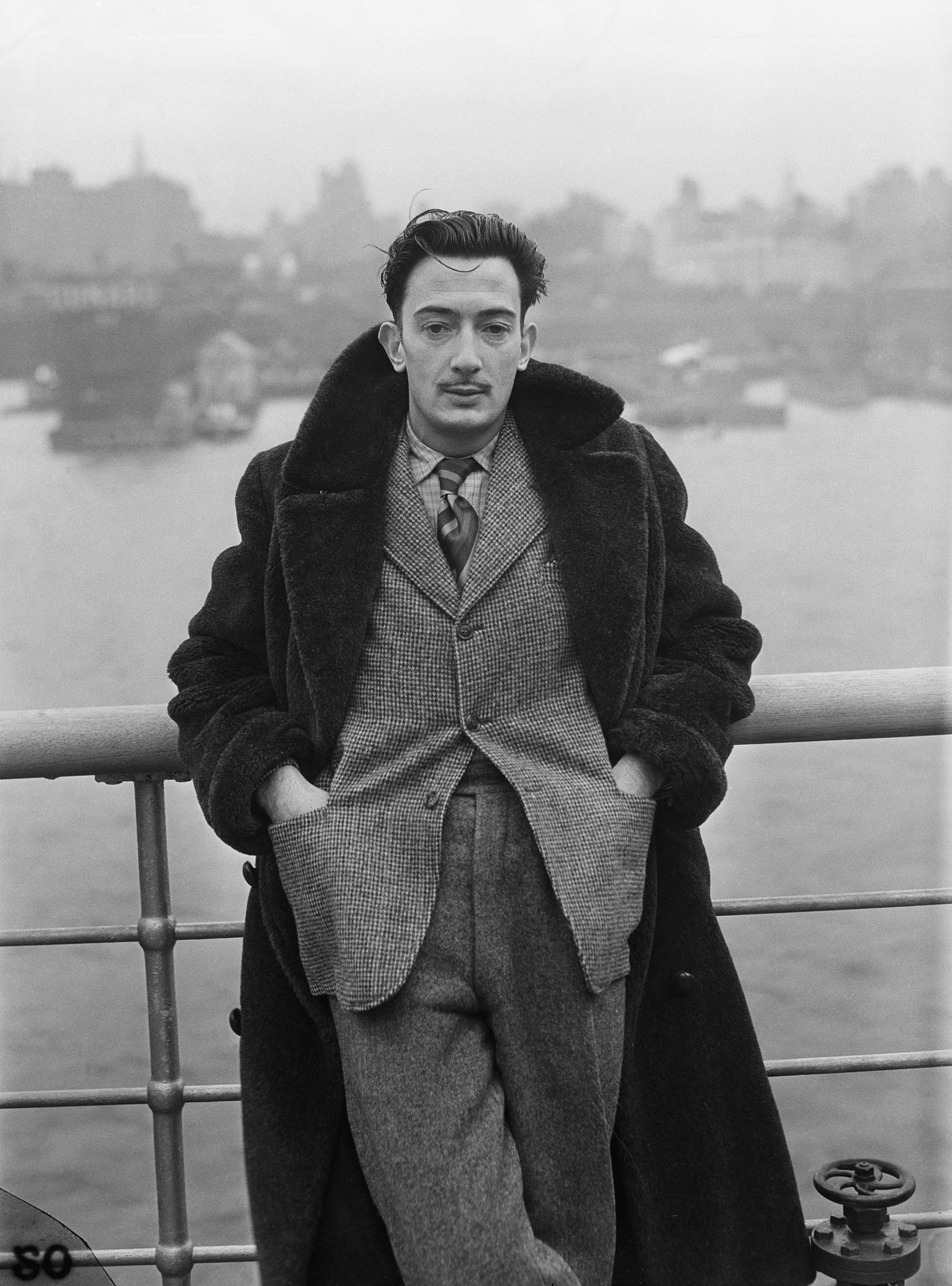

Savador Dalí is one of the most recognizable artists of all time.

He was born Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech in 1904 in Catalonia, close to the border with France.

In the earliest surreal twist of the artist’s life, he wasn’t the first Salvador born into his family. His older brother had also been named Salvador but died nine months before the artist’s birth. His lost brother appeared in the painter’s later works, including Portrait of My Dead Brother (1963).

Salvador was drawn to both art and ambition at a very young age. He was described as “dreamy, imaginative, spoiled and self-centered,” boy who was used to getting what he wanted. “At the age of six,” he wrote in his 1942 autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, “I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since.”1

He began to study at the local drawing school at 12 years old, and his father put together an exhibition of Salvador’s charcoal drawings in their family home when he was 13. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theatre in Figueres as a 15 year old.

In 1922, Salvador moved from his hometown on the coast to Madrid to attend the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. By then, his persona had already emerged. “Dalí already drew attention as an eccentric and dandy. He had long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee-breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century.”2

This time in college in Madrid would fuel the best work of Dalí’s creative life. He made close friends with other generational artists as a student, including Luis Buñuel and Federico García Lorca, and regularly tapped the city’s museums for inspiration. Each Sunday morning, he went to the Prado to study the great masters. He read Freud, first encountered Dada and Futurism, and experimented with Cubism during these years. By the time Dalí was 22, Picasso was granting him meetings in Paris, having heard of Dalí’s talents through Joan Miró.

In 1929, Dalí both formally joined the surrealist movement and met his future wife—Gala (born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova).

Gala is an incredibly controversial figure in Dalí’s life—“equal part muse and monster.” (André Breton despised her, and Luis Buñuel loathed so much that he once tried to strangle her.3) Dalí claims to have been a virgin when he met Gala, who “had an uncanny ability to see beyond the strangely handsome young man’s hysterical laughter and scatological humour, which had proved wearying in the extreme to the others.” Gala abandoned the successful poet Paul Éluard for Dalí in 1929, trading a fancy Parisian apartment for a “primitive stone hut” in the Catalonian fishing village of Portlligat to be with the young artist. During this time, his work flourished.

Surrealism has been called “the most popular art movement of the 20th century,” with Dalí as perhaps its most famous figure. Robert Hughes wrote:

Everyone knows something about surrealism…The word has spread so far that people now say "surreal" when all they mean is "odd", "totally weird" or "unexpected". No doubt this would give heartburn to André Breton, the pope of the movement nearly a century ago, who took the title from his friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had called his play The Breasts of Tiresias, "a surrealist drama". But too late now. The term is many years out of its box and, through imprecision, has achieved something akin to eternal life. Surrealist painting and film, that is. In fact, some surrealist images have imprinted themselves so deeply and brightly on our ideas of visual imagery that we can't imagine modern art (or, in fact, the idea of modernity itself) without them.4

As Dalí’s fame and fortune grew, he cultivated his image both as an artist and a work of art himself. He and Gala “carefully choreographed appearances which all formed part of the ‘Dalían project.’”5 Robert Hughes writes that “He was the apotheosis of the dandy, a now almost extinct breed; and he grew famous through shock-effects and scandal, whose manifestations in painting no longer stir the shock-proof, media-glutted culture of our own time.” 6

Dalí’s public acts began to draw more attention than his artwork. In 1941, the Director of Exhibitions and Publications at MoMA wrote: "The fame of Salvador Dalí has been an issue of particular controversy for more than a decade...Dalí's conduct may have been undignified, but the greater part of his art is a matter of dead earnest."7

Many of Dalí’s stunts involved exotic animals. Much of the writing you’ll find online saying these animals were Dalí’s pets are exaggerated—most photographs with animals were posed. None were beloved companions, all were tools for photographs and actions that grabbed our attention.

This detachment matches Dalí’s life and work. He was against his art carrying any kind of message. His paintings, statues, and stunts were simply real-world manifestations of hypnagogic images—the vivid, irrational images you see right before falling asleep.

Let’s take a look.

Here he is in 1950 in Paris, France, taking a goat-led carriage for a posed stroll. By this time, his Velasquez-esque mustache was on full display. (It would only grow larger.)

Here he is signing a contract for a book on top of an ocelot named Babou in 1965. Although many have claimed that Babou was Dalí’s pet, that was not true. Dalí bought the ocelot from a beggar in New York and, when he was done with it, abruptly dropped it off with his secretary John Peter Moore for him to took care of. Moore fell in love with Babou, and adopted two other ocelots. He fed and cared for them, paying bills for household items they inevitably damaged. Dalí only borrowed Babou as a “provocative accessory.”8

Then there’s the famous photo of Dalí taking an anteater for a stroll in Paris in 1969. This was also entirely posed. He borrowed the anteater from the Paris Zoo.

Two years later, he brought a much smaller anteater with him onto Dick Cavett’s TV show. The first few minutes are worth a watch. You can see Dalí’s lack of interest in the animal.

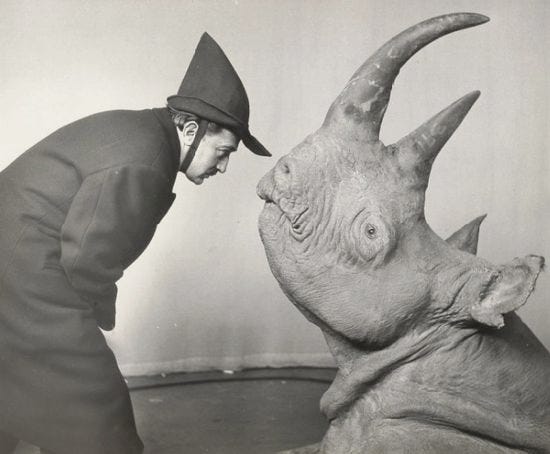

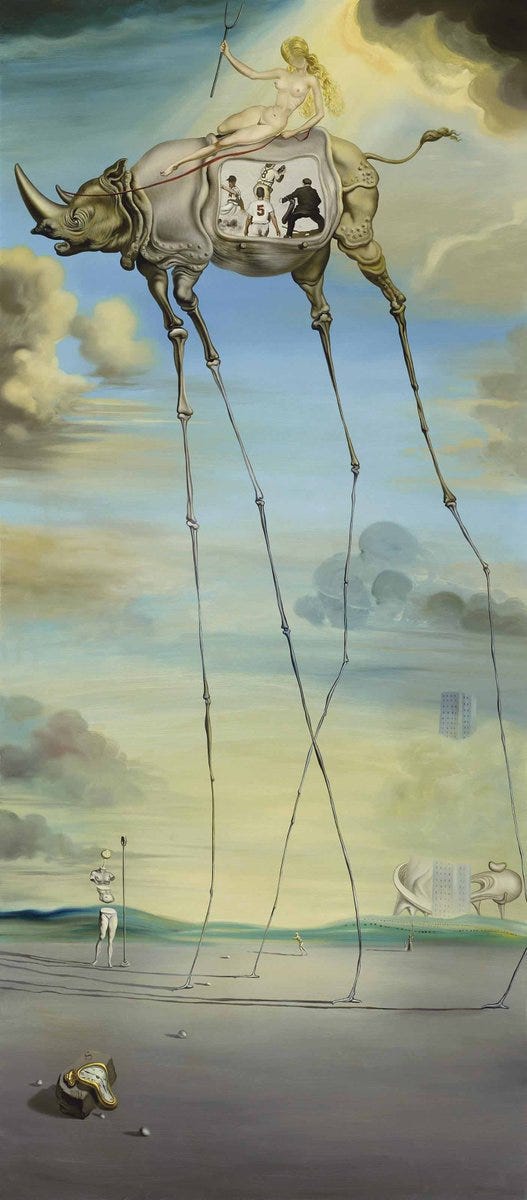

Dalí says in the video that he doesn’t like any animals except anteaters and “violent rhinoceros.” Those two animals are the only two “angelic animals” according to Dalí “because of their tongues.”

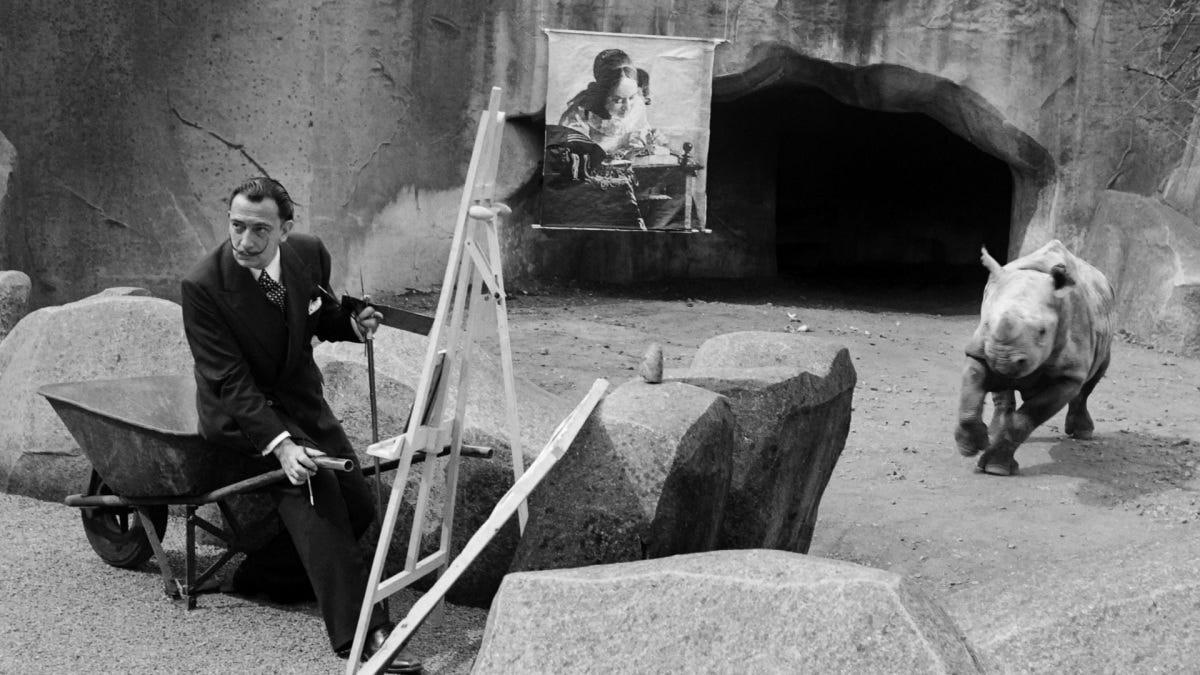

Rhinoceros also showed up in Dalí’s stunts. In 1955, Dalí brought several copies of one of his favorite paintings, The Lacemaker by Johannes Vermeer, to a zoo. He displayed the copies next to himself while he painted, perched on a wheelbarrow, in the same pen as a rhinoceros named François.

Dalí's assistants then dangled a poster of The Lacemaker in front of the rhino, hoping it would charge through the masterpiece with its horn. The rhinoceros didn’t comply, so Dalí took matters into his own hands. You can watch that for yourself here as—of course—it was captured on film.

In 1959, Dalí had a rhinoceros paint its own artwork by stepping on a paper with ink, and then the same rhino ate the piece.

Upon browsing through all of these videos of Dalí’s exotic “pets” and stunts, I couldn’t help but feel a parallel to the influencer antics we see so much of today. Examples are all around us.

For Dalí, as for today’s celebrities and influencers, animals are magnetic symbols. They grab our attention when removed from nature and thrust into unusual scenes for the camera. It’s hard to look away.

In 2021, Amanda Hess interviewed a suite of YouTubers with channels about exotic animals, including Tomas Pasiecznik, who lives in New Jersey with his parents, “his dog and 26 other species of animals, including a reticulated python, a Chilean rose hair tarantula, a colony of Central American giant cave cockroaches and an African pygmy hedgehog named Chloe.” Pasiecznik told Amanda, “A large number of pets is not my goal, but a large number of pets gets views on YouTube.”

Clearly I love animals, but I’m not an animal activist. Perhaps I’m not morally alive enough to take such a stance. What does interest me in this post is Dalí’s legacy—whether or not his work has meaning for me, or lasting power in our culture.

And I can’t help wondering: Did Dalí help initiate the culture of empty visual spectacle we’re living in today?

Surely Salvador Dalí’s work had technical skill and for him, most symbols weren’t one-time-use. He returned, for example, to the rhinoceros over and over in his life. And, you can’t deny the man’s sense of humor.

But many believe Dalí’s antics ultimately overshadowed his artistic legacy. Art critics argue that he peaked artistically in his 20s and 30s, then gave himself over to exhibitionism and greed. (He died in 1989 at age 84.)

When Dalí was 74, he was elected to the French Academy of Fine Arts in 1979, and a peer said that he hoped Dalí would now abandon his "clowneries."

Those hopes proved futile. Writing in The Guardian, critic Robert Hughes said that Dalí’s early work surpassed Picasso’s but that his later works became “kitschy repetition of old motifs or vulgarly pompous piety on a Cinemascope scale.” When Dawn Ades of England’s University of Essex, a leading Dalí scholar, began specializing in his work 30 years ago, her colleagues were aghast. “They thought I was wasting my time,” she says. “He had a reputation that was hard to salvage. I have had to work very hard to make it clear how serious he really was.”

I experienced Dalí’s late-stage “kitschy, pompous piety” for myself when I visited the Dalí Theatre and Museum in Figueres, Spain, where Dalí’s body is interred. The museum is a cluttered wasps nest of empty symbols. The facade is topped with giant eggs, there are walls of bread, corridors full of strange attractions such as a car full of plants and snails that rains inside. I felt the camp, but nothing more. The pair of lobster socks I bought in the gift shop and the friends I shared the day with are the only things that will stay with me from that visit. Dalí had told me nothing, and, to my eyes, his aesthetic sensibility had so obviously diminished with age.

The contemporary performance artist Taylor Mac once said: “An artist’s job is to dream the culture forward.”

When we strip the meaning out of art, and mistake spectacle for aesthetics, all we are left with is cheap visuals—in today’s terminology, content. The result for me has been an increasingly surreal world.

Is this what Salvador Dalí’s dream for us was? Did he ever have a dream for culture, or just a dream for himself?

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, London, Faber and Faber, 1997 p. 90

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180822-gala-dal-monster-muse-or-misrepresented

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/mar/13/art

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180822-gala-dal-monster-muse-or-misrepresented

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/mar/13/art

Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, London, Faber and Faber, 1997 pp. 413–14

https://arthive.com/publications/4104~Famous_artists_and_their_pets

Mind provoked! Intrigued!

Very robust, fair and thoughtful piece. There was much in here about Dali I didn't know. Thanks Bailey!