Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Takashi Murakami has been described as “Japan’s answer to Andy Warhol,” and his art as “instantly recognizable.” He’s known for blurring the line between commercial and fine art, and his work has “graced handbags, phone cases, skateboards, and album covers.” (It was recently even charbroiled onto a hamburger!1) Takashi has famously collaborated with Louis Vuitton, created music videos with Kanye West and Billie Eilish, and placed his paintings and sculptures in museums across the globe—even in Versailles.

Takashi Murakami was born in 1962 in Tokyo. His father was a taxi driver and his mother a housewife. He attended Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music, Japan’s most prestigious arts institution, and holds a Ph.D. in nihonga, a rarefied branch of present-day Japanese art.

Murakami grew up in an era when, as Peter Schjeldahl wrote, “young Japanese chafed at their rehabilitated nation’s banality, which they experienced as impotence in a society whose economic success and, to an extent, cultural fashions hewed to Western models.” As Takashi recalled of his childhood:

Western paintings were being brought into the country, and going to exhibitions had become a very popular pastime. Every Sunday, my parents would take us to see these works, and I detested the experience.

As a child, looking at paintings was absolutely boring.

One standout memory was when, around the age of 8, I had to wait in line for three hours with my family, just to see the Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s painting at a museum in Tokyo. The work depicted Titan Cronus (or Saturn) eating his own children. The image was haunting and kept me up for many nights after. I think this profound experience, or trauma, formed the basis for my act of painting to this day. It taught me that if my work doesn’t move people and induce a “wow!” then it’s all for nothing.

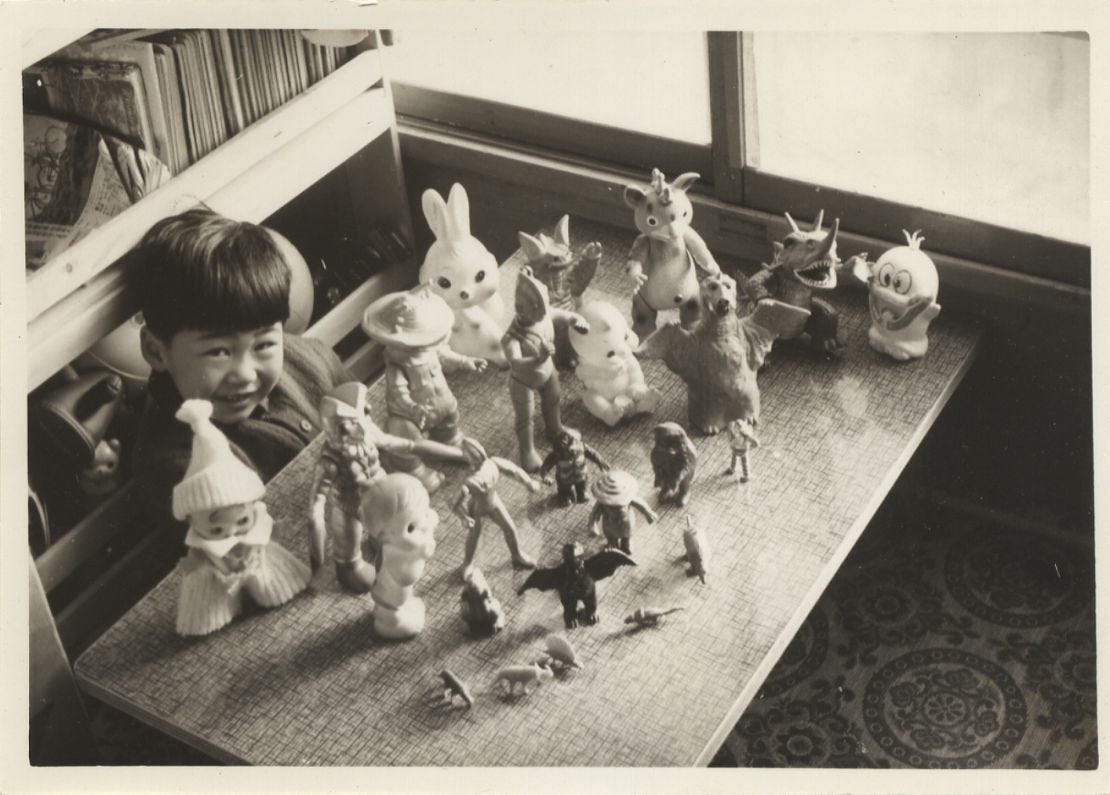

Takashi felt that the respectable Japanese artists he observed when he was younger were ignoring the horrors and humiliations of World War II and the postwar occupation. But the otaku, or “the geeks,” he found himself hanging out with in the seventh grade were facing harsh realities head on, and translating their experience into cartoonish fantasy. Takashi directed himself towards the aesthetic, “rushing headlong into becoming a full-fledged otaku.”2

Takashi Murakami had his first solo show in 1989, and around that time had started traveling to New York City to tap into the art scene. But he spent years struggling to make a living. “I don't have a prominent family background, and I became famous very late. At the age of 36, I was still living on expired fast food lunch boxes,” he said.

Takashi first began to gain attention for his “otaku” works in the early 1990s, the most popular of which are explicit enough that I’m going to bypass posting them here. (I work at Substack! My coworkers read this!) If you want to see one of his most famous pieces, go here.

By the mid-1990s, he had shifted his aesthetics. As The New York Times explained:

If you were to draw a map of Japanese popular culture…you might say that male-oriented otaku culture lies at one pole and that the female domain of kawaii (cuteness) is situated at the other. In the mid-90's, Murakami set sail from otaku toward kawaii.

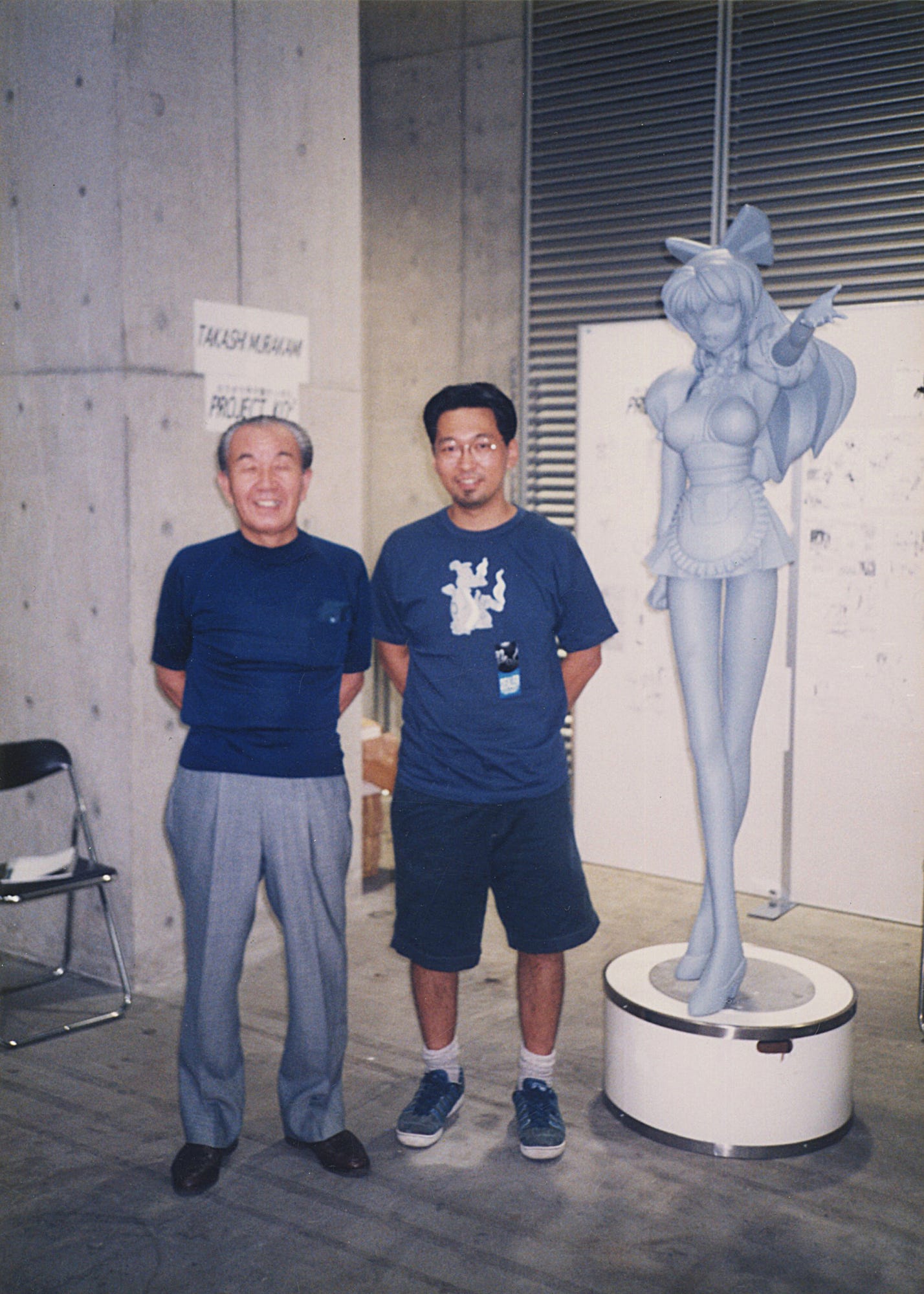

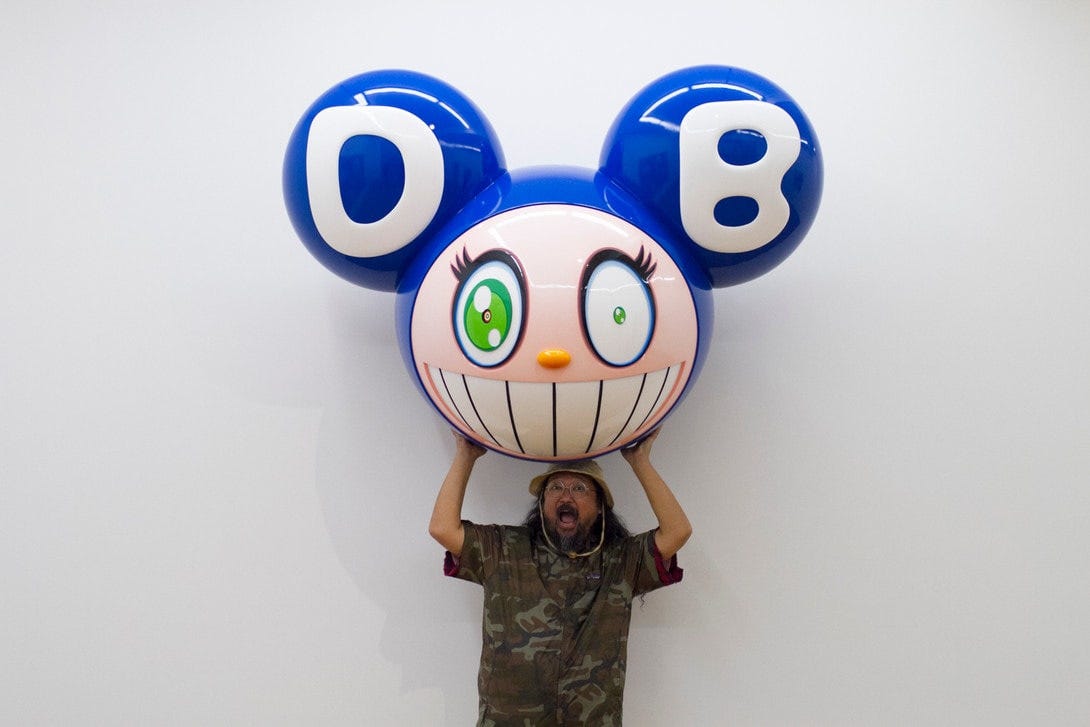

Cute cartoon characters started showing up in Takashi’s work, reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s images of Mickey Mouse and Roy Lichtenstein’s re-use of comics. Takashi Murakami, however, created his own characters. Here he is with his first, Mr. DOB, his answer to Mickey Mouse:

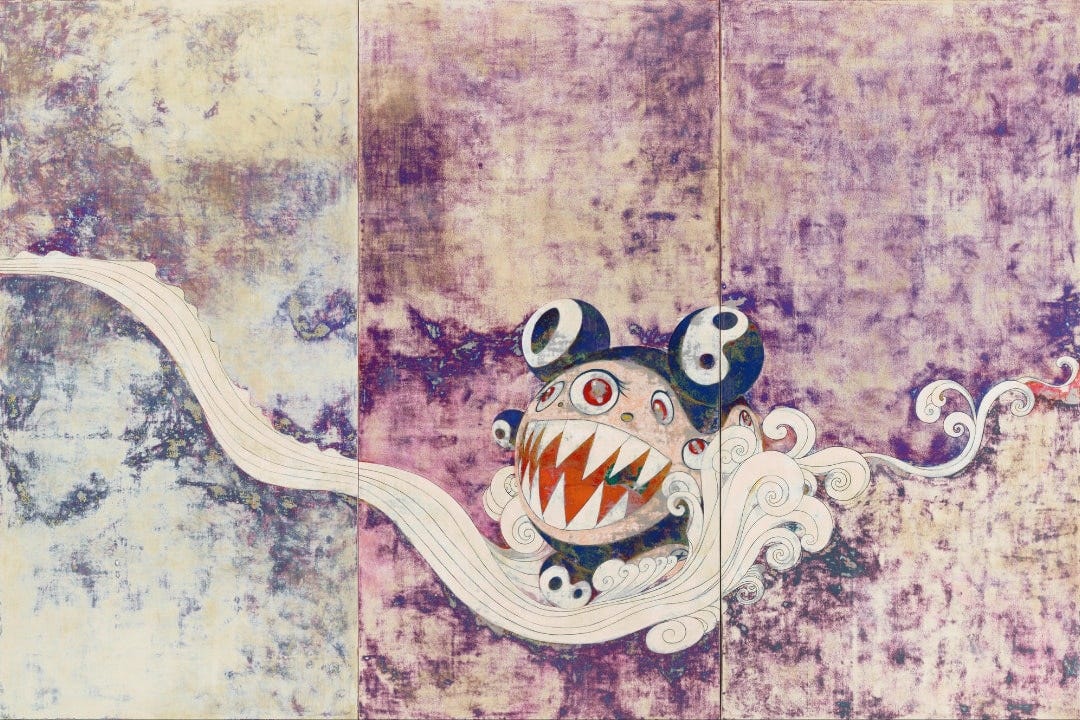

Takashi threw himself into research to analyze the principles of kawaii, and later told The New York Times "I found a system for what is a cute character." Through the 1990s into 2000s, he released numerous signature kawaii characters, including smiling flowers and colorful mushrooms. By 2003, the artist’s work was in “great demand,” selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Around that time, in 2006, a real-life cute character came into his life, a dog named Pom.

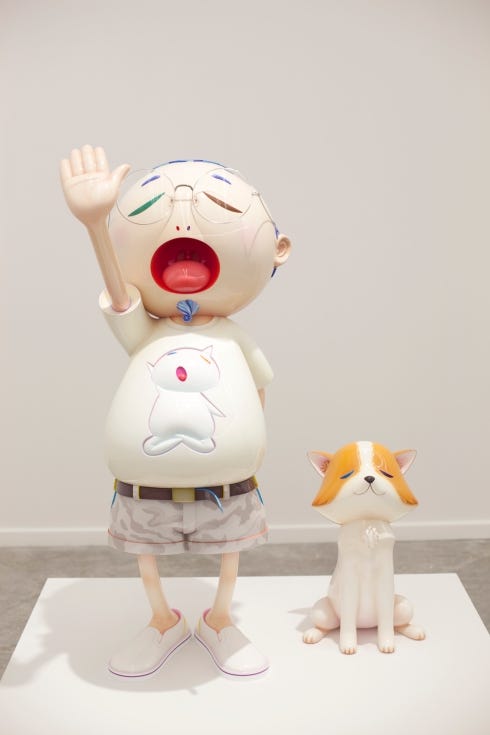

Pom made his way into Takashi’s artwork, including this piece, which was included in the show at Versailles.

And Pom was a frequent presence in his Instagram posts. Takashi Murakami was one of the first major artists to use the platform (I worked there in the early days), but until doing this research, I never realized that he had fused his dog’s name and his own to create his username: @takashipom.

He even turned his Instagram avatar with Pom into an artwork. The artist created this piece of him and Pom in 2019, while she was in the midst of a battle with cancer.

In October 2020, Takashi Murakami took to Instagram to share sad news. “My beloved dog POM passed away at 9:34 am on October 3. 🙏 I join my hands in prayer. 😭”

He continues:

My username is takashipom, which combines my and POM’s names. With POM gone, I feel indescribable sadness as though I have lost half of me.

POM was born on the island of Yoron, close to Okinawa. The first time I ever visited the island, I met her as one of the many puppies just born in the corner of a hotel. Of the seven puppies, I brought four back with me to Tokyo and gave three away to my friends, keeping POM with me.

Until I started living with her, I had no clue how a dog can take up such a significant place in our lives. And now with her gone, I’m at a complete loss as to what to do next. Perhaps this is a common conundrum with pet owners… Should I get a new dog? Or should I live with POM’s memory in my heart and continue to mourn her? I honestly don’t know what I should do. I have to say, though, that for the last year and a half of her life, POM was battling cancer, and one of my studio staff was kindly taking care of her, bringing her to the vet and getting her through surgeries. I felt so bad to see POM go through it all, and did question myself whether it was really the right thing to do.Though POM may be gone, I will not change my username takashipom.

But this is so sad. So profoundly sad. It didn’t hit me immediately after her death, but as more time passes, my sense of loss seems to spread wider and deeper within me. I pray for the repose of her soul, imagining the day I will eventually join her where she is. Farewell, POM!

Upon reading Peter Schjeldahl’s essays as research for this post, he doesn’t have much nice to say about Takashi Murakami. “I don’t like Murakami’s work,” the much-revered art critic wrote just before admitting that he had never visited Japan.3 Schjeldahl called Murakami “the master of plastic-fantastic puerility.” The critic sounds a bit like General Douglas MacArthur in these moments, who in a speech to a Senate committee in 1951 said that when "measured by the standards of modern civilization," the Japanese people were "like a boy of 12." (The remark ignited a furious response in Japan.) These two foreigners were missing the context and complexity of Japanese culture.

Fortunately, Japanese art historians have contributed what Peter Schjeldahl and other Westerners couldn’t grasp. They describe the art world in Japan as fundamentally different from the West. In Japan, low and high art lack a strong division. “In Japan, a gallery has no meaning, and a Louis Vuitton shop is a more powerful place to see something,” Tomio Koyama, Murakami's dealer in Tokyo, told The New York Times. Up until when Japan embraced the West in 1868, the Japanese language didn't have a word for “fine art”—the concept was imported by foreigners.

The blurring of high and low remains true today in Japanese society. “This back and forth [between commercial and fine art] doesn't seem unnatural to us. We have had a long history of museums with department stores as a venue,” Tokyo art critic Noi Sawaragi futher explained. “It was on the 12th floor of the Seibu department store that I developed my knowledge of contemporary art. I saw Marcel Duchamp, Malevich and Man Ray in depth for the first time in that museum. I think it is the same for everyone of my generation. Downstairs you find dresses, bags and shoes, but on the 12th floor you find art.”

In recent years, the art world hasn’t followed Peter Schjeldahl’s preferences. It’s followed Takashi Murakami’s. The New York Times wrote presciently in 2005 that “while it would be fatuous to say that we are all Japanese now, we are surely all living in Murakami's world.” The blurring of commercial and fine art, the personal with the public, and the digital with the physical are now absolutely commonplace.

Takashipom and the otaku led the charge in this seismic change. For better or for worse, the world will never be the same.

Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/28/takashi-murakami-japans-answer-to-andy-warhol

https://www.cnn.com/style/article/takashi-murakami-identity/index.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/04/14/buying-it

Pets, with constant stay, occupy a unique place in our lives. With no hate from them, they occupy a place that humans may not do it consistently.

His art is without a doubt more akin to how Picasso’s work impacted and yet was so obviously a reflection of the world in which it was created. Powerful and of this time and destined to be recognized as perhaps the best of his generation. But great in any case.