Art Dogs is a weekly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, lizards, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these weekly posts to your email inbox.

Greetings friends,

We are 16 editions into this Art Dogs project, which started on a whim (thanks to

) and has evolved into a truly enriching project for me. Thank you for tuning in. It’s a total thrill to have you here.Starting this week, I’m going to play with the shape of the newsletter a bit.

When I started Art Dogs, I expected each post to be quite short—maybe even just a few words and a photograph, inspired by

’s . The very first pieces I wrote about Matisse, Bradley from Sublime, and Tadao Ando held to those shorter lengths.But quickly I began to write longer essays, as one does on Substack. While these longer pieces have been absolute joys to write, I suspect I won’t be able to produce them on a weekly cadence.

So going forward I’ll aspire to just one or two long essays each month, published on Fridays. I hope to still post in the weeks between, experimenting with what shorter posts on Art Dogs can look like.

Amidst this shift, I’d love your feedback If you have any thoughts about what you’d like to see more of here, what posts you enjoyed most, and who I should profile next, please hop into the comments and let me know?

Thank you again for being here and reading Art Dogs. It’s really been fun.

Bailey

Vladimir Nabokov's butterflies

Vladimir Nabokov was one of the lucky ones. He found two all-consuming passions in life—literature and lepidoptery—and excelled at both. Biographer Bryan Boyd once wrote: “No writer of Nabokov's stature, not even Goethe, has been a more passionate student of the natural world or a more accomplished scientist.”

Ever since Vladimir was a five-year-old boy, he was drawn to butterflies. “If my first glance of the morning was for the sun, my first thought was for the butterflies it would engender,” he reflected in 1948 about his childhood.1

Though he endured many disruptions and traumas in his lifetime, from the collapse of the Russian Empire to the loss of family members in concentration camps to multiple emigrations, Vladimir’s passion for butterflies never faltered.

At eight years old, his father was imprisoned for political reasons. When Vladimir visited his cell, he brought along a butterfly.2

In 1918, a 19-year-old Nabokov fled the Russian Revolution with his aristocratic family, relocating from St. Petersburg to Crimea, followed by Cambridge. At Cambridge, he studied both zoology and later Slavic and Romance languages, and even published a paper for The Entomologist in 1920.

In 1940, when he first immigrated to the United States, he spent his earliest days in the country volunteering in entomology at New York’s American Museum of Natural History. Soon after, he began working in universities. He is credited with founding Wellesley's Russian department while simultaneously acting as a curator at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. In those seven years at Harvard, he reportedly devoted as much as fourteen hours a day to drawing the wings and genitalia of butterflies.3

Over his lifetime, he collected more than 4,000 specimens of butterflies, which represented more than 80% of Western Europe's varieties.4 At least 570 mentions of butterflies have been counted in his literary work and more than 20 species of butterfly have been named after his fictional characters. There’s even a butterfly named Nabokovia cuzquenha in his honor.

“I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.” - Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir’s wife of fifty-two years, Véra, proved as indispensable to his work in lepidoptery as to his literature. Véra has been described as Vladimir’s “first reader, his agent, his typist, his archivist, his translator, his dresser, his money manager, his mouthpiece, his muse, his teaching assistant, his driver, his bodyguard (she carried a pistol in her handbag), the mother of his child, and, after he died, the implacable guardian of his legacy.”5 Nearly all of Nabokov’s books are dedicated to her.

Because Vladimir could not drive, Véra transported him to sites so he could collect butterflies. He wrote much of Lolita in the backseat of the family car, a black 1946 Oldsmobile, with Véra at the wheel as they criss-crossed the western United States looking for butterflies. (Véra also famously saved Lolita when Vladimir twice attempted to throw the manuscript into the incinerator.)

Because of the sales and film rights to Lolita and Pale Fire, the couple was able to move back to Europe in the 1960s and Nabokov devoted his time solely to writing and pursuing his passion for butterfly hunting in the Alps.

I love the photos below from that era of the couple’s lives. They seem like stills from a Wes Anderson film.

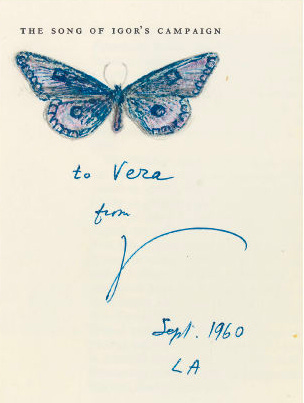

Vladimir Nabokov rarely signed his books—in fact, he reportedly never did so for strangers8 —but he often drew butterflies on copies of his books and those by other authors. Most of these adorned books were gifts for his wife Véra and their son, Dmitry.

Many of these drawings are of made-up species, inspired by specimens from his study but re-imagined and named solely for Véra. Vanessa verae is one such butterfly—a midnight and blue variant of the Vanessa genus.

Given the depth of Vladimir Nabokov’s dual passions, many have searched for a connection between his love for lepidoptery and his literary work. In an essay titled “There is No Science without Imagination, and No Art without Facts: The Butterflies of Vladimir Nabokov,” Stephen Jay Gould argues that Nabokov’s “acute focus, his almost obsessive concern for observation and detail, is at the root of both his success as a butterfly collector and his technique as a novelist.”6

similarly noted in The New Yorker that “the writer and the lepidopterist really do turn out to be the same person, engaged in a single, if multifaceted, project of knowledge and description.”Nabokov would likely have agreed with their reflections. He once wrote: “A writer must have the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist” and “in high art and pure science, detail is everything."

Though he is revered as one of the greatest writers to ever live, Vladimir Nabokov signaled he would have preferred a scientific life to a writer’s life. During an interview in a 1967 edition of the Paris Review, he made the primary source of his enthusiasm clear:

INTERVIEWER: Besides writing novels, what do you, or would you, like most to do?

NABOKOV: Oh, hunting butterflies, of course, and studying them. The pleasures and rewards of literary inspiration are nothing beside the rapture of discovering a new organ under the microscope or an undescribed species on a mountainside in Iran or Peru. It is not improbable that had there been no revolution in Russia, I would have devoted myself entirely to lepidopterology and never written any novels at all.

And one of his poems, “On Discovering a Butterfly,” begins:

I found it and named it, being versed

in taxonomic Latin; thus became

godfather to an insect and its first

describer – and I want no other fame

I find it comforting that even Nabokov believed that he would have rather spent his days directed towards his hobby than his profession. As a younger person, I thought that a meaningful life would require that my vocation and my biggest hobby be fused. Lately I’ve begun to question that.

Aristotle believed there were two categories of activities that give our lives meaning—telic and atelic activities. (Telos in Greek means purpose.)

Telic activities are activities that we aim to complete. Think of running a marathon, writing a book, or getting a Ph. D. They are exhaustible. Once you arrive at your goal, that telic activity is finished. While they offer us accomplishments to drive towards, telic activities also create a paradox: “if you fail, you are unhappy because you failed. But if you succeed, then the pleasure you got from reaching your goal is extinguished right at the moment you do achieve it, or shortly thereafter.”7

Atelic activities, by contrast, do not come to an end and are never incomplete. For me, surfing is one such activity. The value I get out of it has nothing to do with a goal or a final end point I’m hoping to reach—the value is in the doing.

I wonder if our professional efforts are innately telic in nature. For instance, one of the most frequently cited facts about his legacy is that the author never won a Nobel Prize. When a peer, Boris Pasternak, won a Nobel Prize for “Doctor Zhivago” in 1958, Nabokov was so distraught that he “waged a bitter, personal campaign against Pasternak, a nonstop stream of vitriol.”8 Even for a writer as renowned as Nabokov, he couldn’t escape the telic paradox.

While Nabokov accomplished noteworthy things in lepidoptery, it seems that the pleasure for him of hunting and studying butterflies was in the doing. As a hobby, it remained an atelic activity to balance his telic writing efforts.

Maybe it’s better if our vocations and hobbies remain distinct. Only when they fulfill different roles in our lives, offering both telic and atelic meaning, can they keep us in balance. And when we allow such activities to coexist, influencing and even fueling one another, greatness has a chance to emerge, as it surely did for Vladimir Nabokov.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1948/06/12/butterflies-vladimir-nabokov

https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2020/10/carlo-rovelli-places-in-the-world-rules-kindness-extract-vladimir-nabokov-butterflies

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/nabokov-s-butterflies

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5504954

https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2020/10/carlo-rovelli-places-in-the-world-rules-kindness-extract-vladimir-nabokov-butterflies

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/16/silent-partner-books-judith-thurman

https://medium.com/swlh/telic-vs-atelic-activities-and-the-meaning-of-life-abf5ac035599

https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2016/12/02/nabokov-was-such-jerk/PLLEJmD9tqWgj5CSgDumrK/story.html

I love every single one of these posts. I tend to prefer reading the long ones but I'm here for the short ones as well. They all delight me.

I am an animal enthusiast AND a former artist (very unknown!) until RA took it away (no whining just stating the facts ; ))

I have commented very little, if at all, but I do enjoy reading all of the stories and seeing the art.

I figure this was as good a time as any to comment!

Thank you