Art Dogs is a monthly dispatch introducing the pets—dogs, yes!, but also cats, turtles, marmosets, and more—that were kept by our favorite artists. Subscribe to receive these posts in your email inbox.

Yayoi Kusama is a great artist.

She’s a “creative polymath” who can span the artistic gamut: painting, drawing, collage, sculpture, performance, film, printmaking, installation, and environmental art as well as literature and fashion. (In addition to visual art, she has published eight novels and several books of poetry.1)

Yayoi boasts the highest auction prices of any living female artist. (The highest price for any woman artist, living or dead, belongs to her mentor, Georgia O'Keeffe.) She even has her own museum in Tokyo.

And like Georgia O’Keeffe, Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and more, she transcended the art world to become an instantly-recognizable visual style.

Some of this comes from Yayoi Kusama’s ceaseless appetite for promotion. She pursued collaborations with many of the world’s biggest brands—handbags with Louis Vuitton, bottles with Veuve Clicquot and Perrier, cotton shirts with Issey Miyake, and more.

And when Instagram came out, it carried Yayoi’s aesthetic to countless screens around the world.

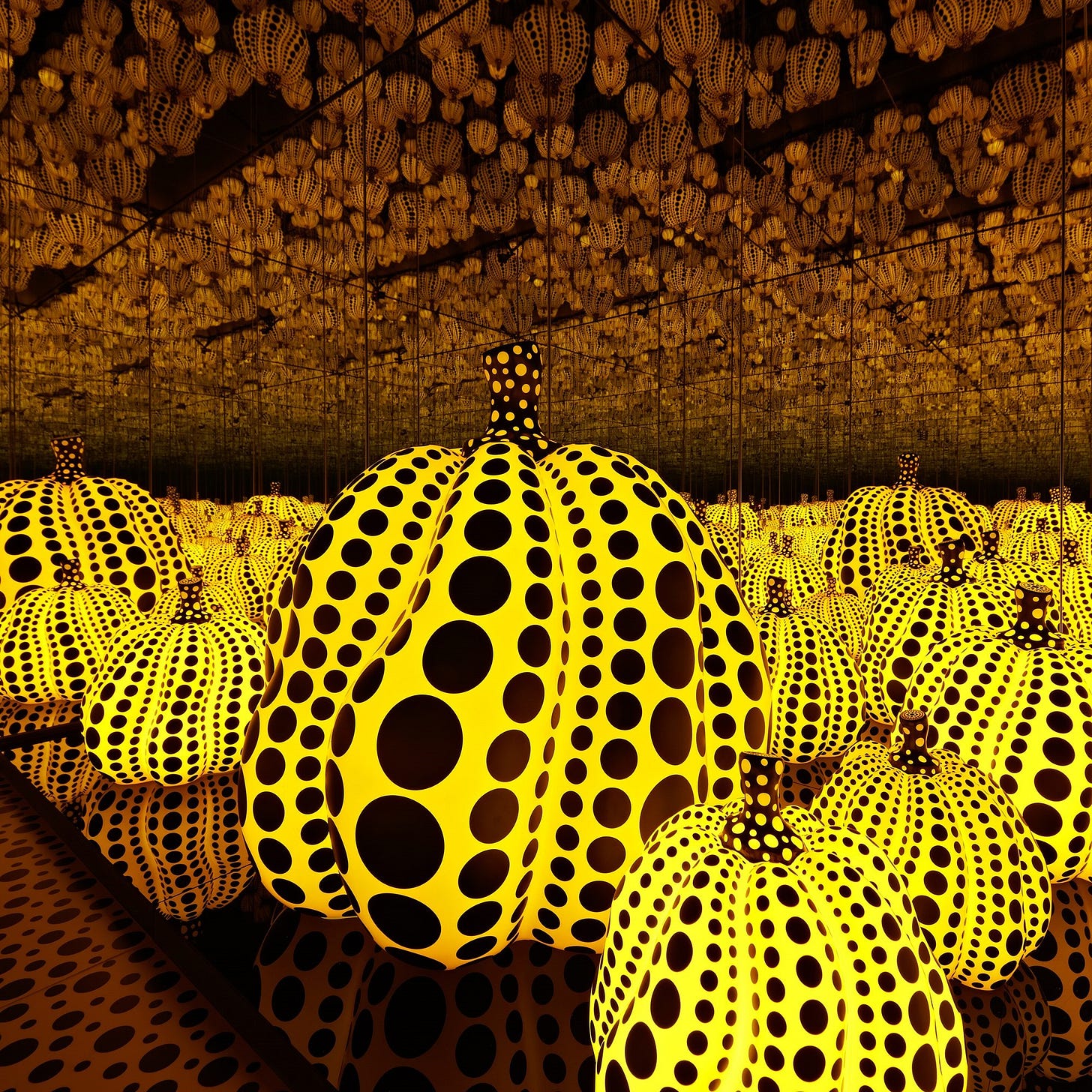

Millions of people have spent hours of their lives in line waiting for the chance to experience—and photograph—her Infinity Mirror Rooms. (Adele even performed in one.) These rooms have been called “the ultimate Instagram exhibition.”

Yayoi’s omnipresence has fed the ire of some art critics. Adrian Searle from The Guardian disparaged the Infinity Mirror Rooms as being more about the photograph than the concept, describing them as “an Instagram experience posing as art,” and resembling “cheapo garden fairy lights.” Will Heinrich wrote in The New York Times that her work is “as familiar, and as reliably perfect, as Coca-Cola.”

But don’t let the popularity she’s earned confuse you, as it has these critics. Even cynical people can’t help but love Yayoi Kusama’s work when they stand amidst it.

Because Yayoi Kusama is a great artist.

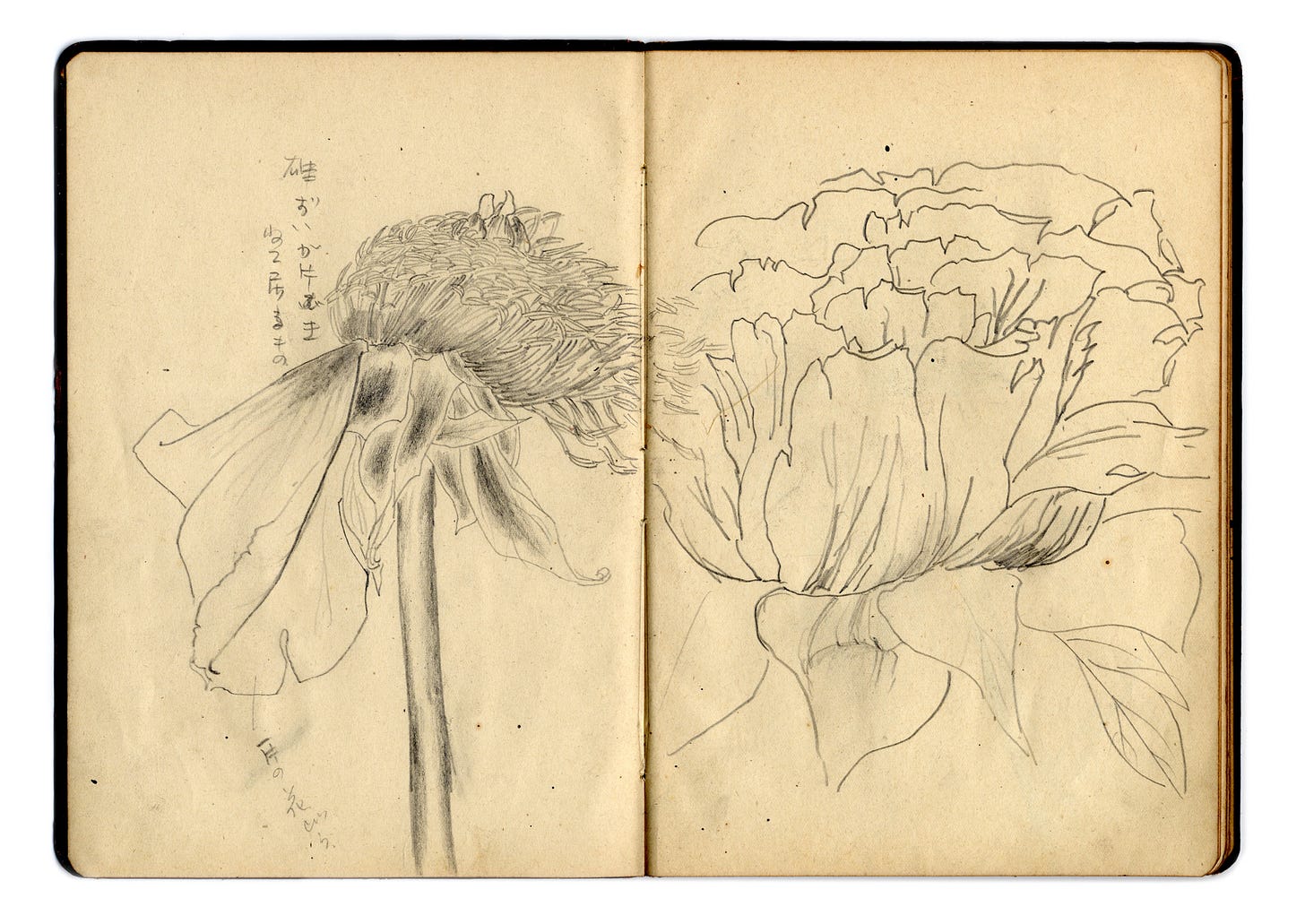

Yayoi Kusama was born in Matsumoto City, Nagano, Japan, in March 1929. (Yayoi means “March” in Japanese.) Her family was wealthy and owned a business cultivating plant seeds. Yayoi spent her childhood amongst their flower fields while the Great Depression and World War II brought her country to its knees.

Yayoi’s parents didn’t support the creativity that burst forth from their daughter. She made thousands of small paintings and drawings during her early years, some of which she later developed into sculptures. Her mother would reportedly rip these early artworks straight from Yayoi’s hands before she could finish them, forbidding her from creating art, throwing away her inks and canvasses, and telling her daughter that one day she would have to “marry someone from a rich family and become a housewife.”

This environment drove Yayoi to practice art as an act of opposition in all forms including her clothes, which she began to rebelliously decorate with dots as a child.

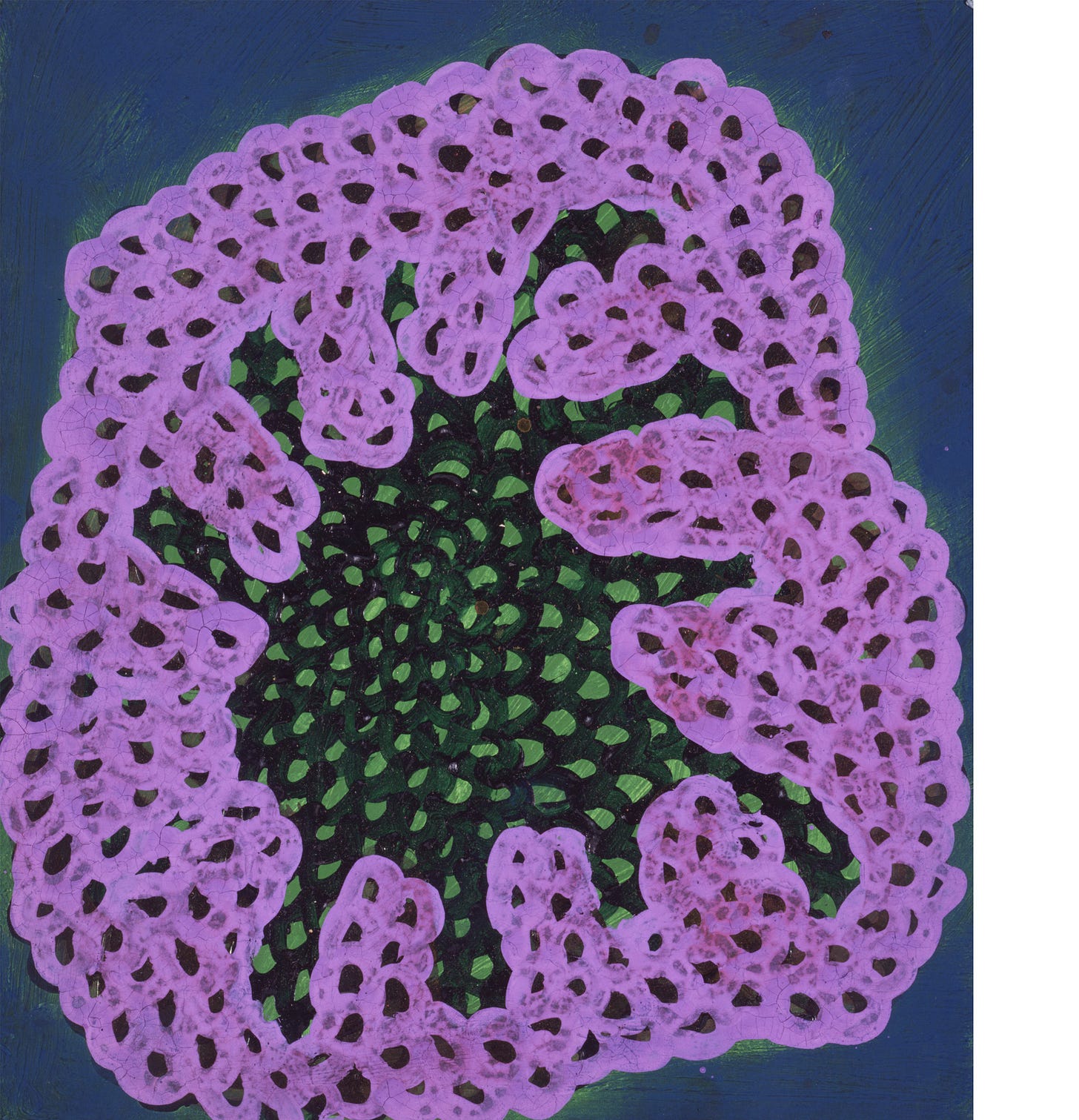

Yayoi has said that she first started experiencing hallucinations at a young age, and they have informed her art ever since. She can recall exploring the fields outside of her childhood home and seeing patterns in the “overwhelming amount” of flowers. Her hallucinations left her “dazzled and dumbfounded,” with repeating patterns flooding her field of vision, an experience she came to refer to as “obliteration.” Yayoi’s artworks aim to help us “obliterate the self” and the process of making them has helped her to transcend her troubles. She later said that she “kept trying to make my own world” as a way to cope with trauma and anxiety.

In her late 20s, Yayoi left Japan and her family behind for a new world—America. She said that Japanese society was “too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women” for her to remain, but this move was no trivial act. In the immediate postwar period, “it was rare enough for a young Japanese woman to travel to the U.S., much less with the intention of becoming an art star.”2

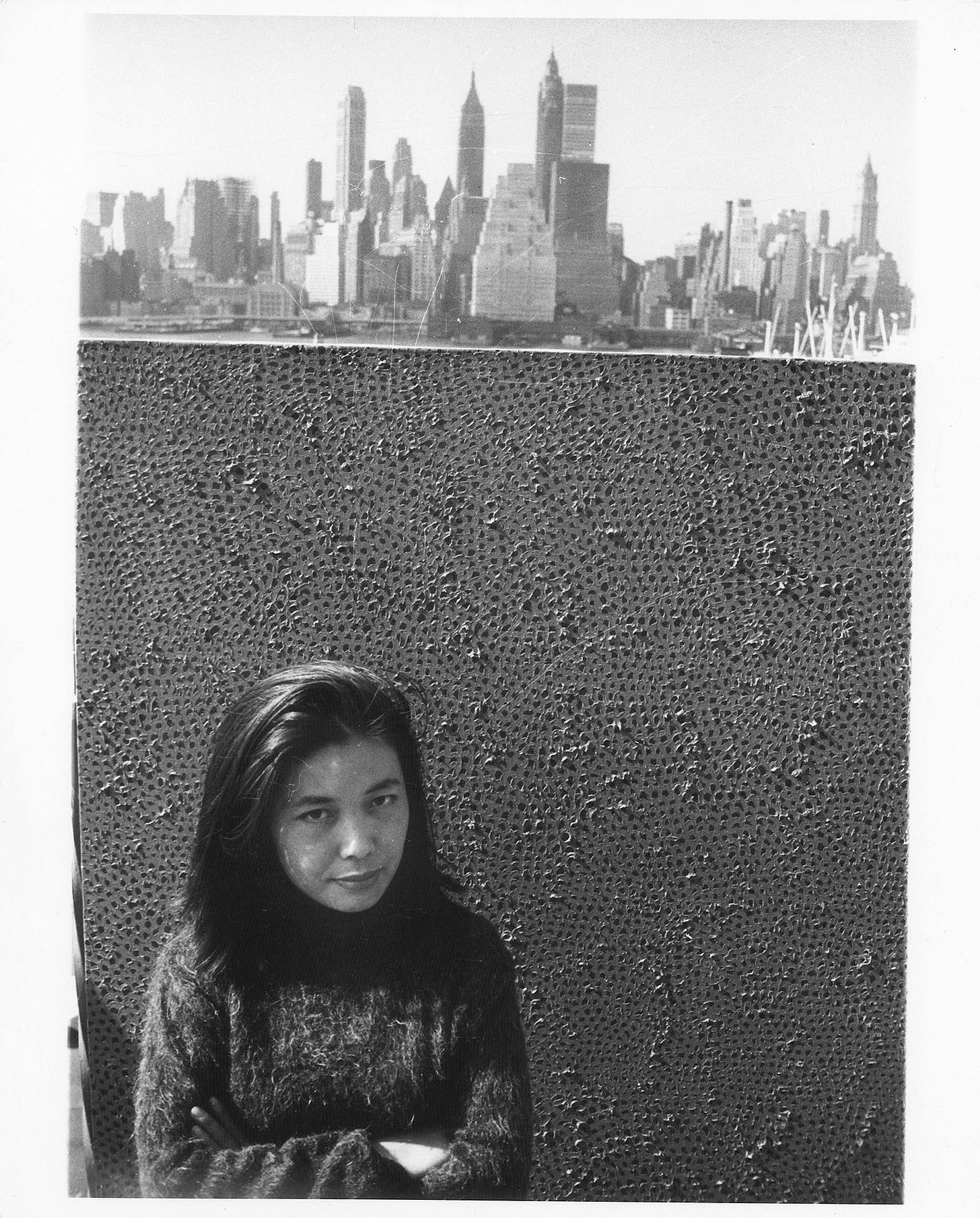

She arrived in Seattle “with no one waiting for her on the other side” and spent six months on the West Coast making art before heading to New York in 1958.3 Of Yayoi’s early conviction, Tate curator Frances Morris said:

“She was on a train to stardom. She knew exactly what she wanted to do. She had a suitcase full of drawings, and she set about selling herself.”4

In New York, Yayoi quickly established a reputation. Within the year, her net paintings were being praised as groundbreaking. Arts magazine exclaimed that she was “one of the most promising new talents to appear on the New York scene in years.”

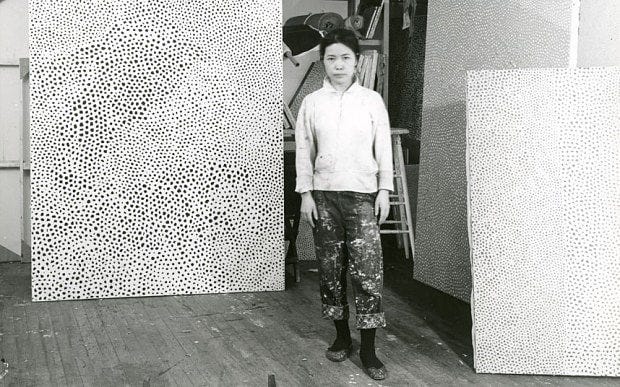

Yayoi didn’t settle. She explored new fabrication processes and materials, including soft sculpture, repeat imagery, mirrors, and lights. As a young artist, she embodied a central tenet of contemporary art that “art must enact rather than simply depict its own transformational capacities.” And she manipulated each material to embody her signature aesthetics.

Art critics have since credited Yayoi Kusama as one of the central nodes pushing the boundaries of the 1960s New York art scene. But at the time Yayoi struggled to earn a living or gain mainstream recognition. It’s widely believed that male artists like Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol copied her signature concepts.5 Yayoi was left to watch in despair as “these ideas—her ideas—manifest in wealth and success [for Warhol and Oldenburg] that she could not herself achieve.” Meanwhile, Yayoi lived in harsh poverty. In her autobiography, she recalled using a door found on the street for a bed, painting during the night to keep warm, and eating “from the fishmonger’s rubbish.”6 (The relevant chapter of her autobiography is titled “A Living Hell in New York.”) She increasingly isolated herself, covering the windows of her Greenwich Village studio to prevent other artists from seeing her ideas.

To avoid other artist’s mimicry, Yayoi began to focus on performance art.

In response to not being invited to the 1966 Venice Biennale, Yayoi smuggled 1,500 plastic-metallic balls onto the lawn of the Japanese pavilion— her first successful experimentation with performance . (Japan didn’t formally invite her to represent the nation until 30 years later. She was the first solo female artist to represent Japan, in 1993.) The artwork directly references the story of Narcissus. Her reflective spheres resemble a fortune-teller’s crystal ball. When gazing into them, viewers see only their reflections staring back. Yayoi acted as a street peddler at the event, selling the mirror balls to passers-by for two dollars each. She was stopped by Biennale authorities who kicked her out, objecting to her selling her work “like hot dogs or ice cream cones.”

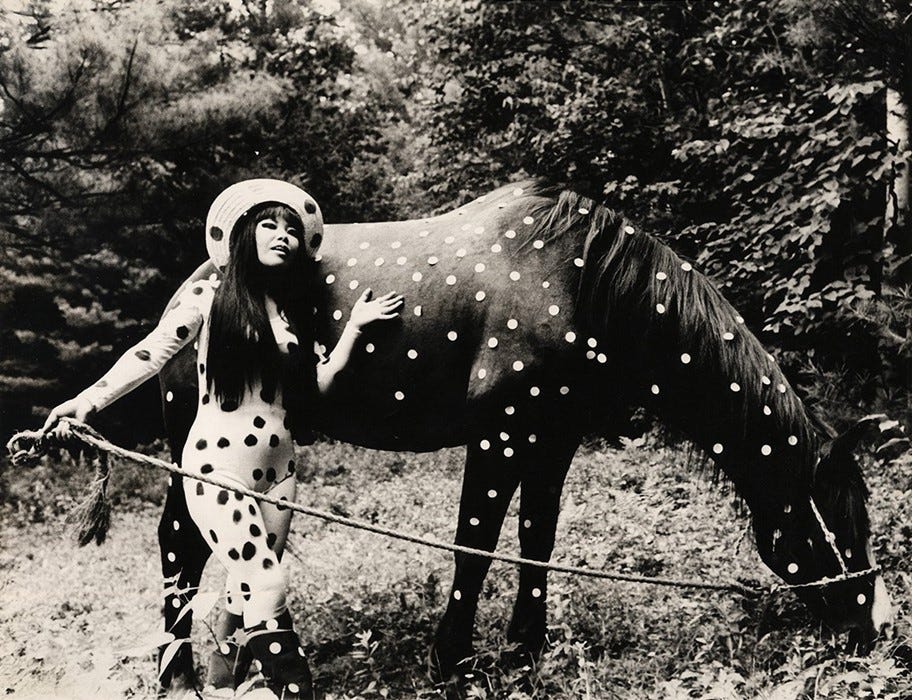

Back in the U.S., she started staging “polka dot happenings,” or “body festivals.” She took these happenings to iconic locations, including the Brooklyn Bridge, MoMA, Washington Square and Times Square. Yayoi asked participants to strip naked, and painted their bodies, often with polka-dots, with the intention of promoting peace or protesting the art establishment. Yayoi used polka dots to “make everything the same, to become one with the universe, and fight back against American individualism.”

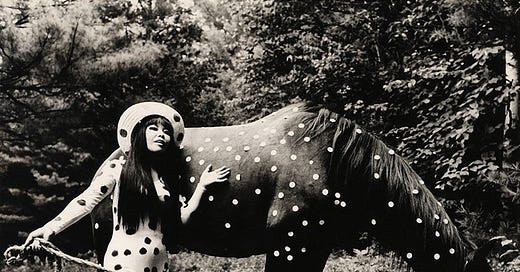

In 1967, Yayoi Kusama released a 23-minute film called Self-Obliteration that documents her notorious happenings. The film can best be described as trippy. At 2:00 minutes, Yayoi presses polka dots onto the skin of a horse, which she then mounts to ride to a polka dot coated lake while wearing a red polka dot gown. Things only get weirder from there.

Your first-blush impression of these performances might be to call them stunts and Yayoi a “media-manipulating show-off.” Will Gompertz writes:

That was certainly the opinion the press reached in both America and Japan by the early 1970s. And they were right, up to a point. She was and is a savvy operator when it comes to attention-grabbing public relations. But with good reason. First, she had to stand out and stand up for herself to have any chance of making it as an unknown Japanese woman in the man’s world that was America’s post-war art scene. And second, she is her art, inside and out. She turns her panic-inducing alarm into positive, life-enhancing experiences.

In response to new forms of struggles and oppression in New York, Kusama had yet again made her own radical world.

But all of this hustling would take a toll on Yayoi. She returned to Japan in 1973 “in a desperate state, having had physical health issues and, on top of that, suffering a nervous breakdown and a subsequent depression that she struggled through on a daily basis.”7 Four years later, she voluntarily checked into a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo, and the world forgot about her.

But Yayoi never stopped making her art.

Most every day for the last fifty years, Yayoi Kusama has woken up in the same hospital in Tokyo, walked to her studio a couple of blocks away, sat down and worked through the daylight.

While she repeated that cycle over and over, the world changed around her.

It started with curator Alexandra Munroe, who organized a retrospective of Yayoi’s work at the Center for International Contemporary Arts in New York in 1989.

Then Japan asked her to represent the country in 1993 at the Venice Biennale, where Yayoi installed an Infinity Mirror Room and reprised her Narcissus Garden.

This time, Yayoi wasn’t kicked out of the Biennale. Nor were her concepts stolen by a male artist. No, this time Yayoi was treated in a way she’d rarely experienced in her lifetime: she was embraced.

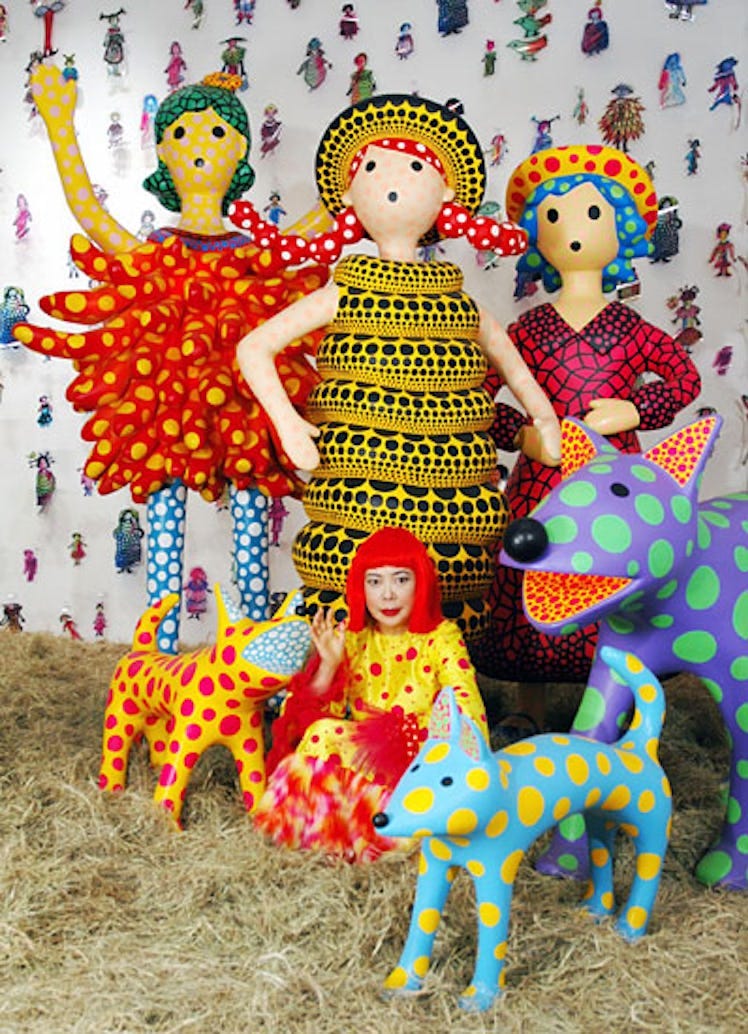

Since that shift in the early 1990s, Yayoi Kusama has become the most recognizable artist on the planet. Her art has been shown at the most prestigious galleries and museums. Paintings she once sold for $200 now fetch upwards of $10 million at auction. Her home country, where she was once shunned, has awarded her its most prestigious prizes. And her style is hers and hers alone—no one would dare copy her.

My favorite essay on Yayoi Kusama comes from Will Gompertz in LitHub.

Yayoi Kusama is far from unique in using art as therapy to overcome extreme anxiety; fear is one of the most common sources of creative inspiration. But her psychological experiences are unique, as are yours and mine. They could have crushed her, but instead they were the making of her. She used them to see and be seen, and to become one of the most original, ground-breaking artists of our time. She says she was born into a family and a culture that suppressed emotions, but despite resistance from her parents and periods of ridicule during her career, she has prevailed by showing the world the healing power of confronting the thoughts that frightened her.

It’s this courage that we must remember when we see Yayoi Kusama’s work today. Against all the odds, Yayoi Kusama has survived to 95 years old. She spent nearly nine decades trying to carve out her own world with little-to-no support systems, and she has finally succeeded. We are lucky to be bearing witness to the late stages of this great artist’s career. This daughter of seed cultivators is in full bloom, and her “Kusama worlds” are on display around the world for us to step into. How lucky are we?

Yayoi Kusama’s Dogs

I found this fantastic photo of Yayoi with an unknown dog and cat in her studio in 1958 in an art book. Despite my best efforts, I can’t find any info about the photographer or the animals online. (If anyone has intel, please share!)

Perhaps this studio dog inspired a series of sculptures that Yayoi created in the 2000s. She’s made fiberglass and balloon dogs, and even a limited-edition dog cell phone.

(These sculptures cost ~$250k. If anyone would like to buy one for me, I’ll happily accept.)

Bonus: The music video Yayoi Kusama made with Peter Gabriel

Released the same year at Yayoi’s return to the Venice Biennale.

https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/21-facts-about-yayoi-kusama

https://nymag.com/arts/art/features/yayoi-kusama-2012-7/

https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/yayoi-kusama-1929

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yayoi-kusama-8094/obsessed-polka-dots

From the Tate’s Katy Wan: “There are arguments that her work has anticipated some of the practices of other, better known artists. Like Oldenburg, in terms of her innovations in soft sculpture which pre-dated his, and Warhol, in the form of the repeat motifs on wallpaper. Her use of repetition preceded Andy Warhol's by about three years and, as a woman working in the male-dominated art world at that time, that’s really remarkable.”

Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama

https://lithub.com/how-yayoi-kusama-transformed-her-terrors-into-art/

How to boil this down to all the thoughts that come into my mind about art and artists is like an infinity mirror in my mind. Thank you for sharing this and I'll take a dog sculpture, too. Anyone?

So very interesting. Thank you.